How a flock of geese saved Rome

The Gauls

In the summer of 390 BCE, the fledgling city of Rome faced one of its darkest hours. The Gauls, a fierce and nomadic Celtic tribe led by their chieftain Brennus, descended upon the city with devastating speed and ferocity. This event, known as the Sack of Rome, would leave an indelible mark on Roman history.

The trouble began when the Gauls, seeking new lands and resources, moved southward into the Italian peninsula. Their path of destruction led them to the Battle of the Allia, where they met the Roman forces on July 18, 390 BCE. The Romans, unprepared for the Gauls’ unconventional and brutal tactics, suffered a crushing defeat. The survivors fled in disarray, leaving Rome woefully unprepared and vulnerable, especially since it had just exiled the celebrated commander Camillus on corruption charges. The Gauls marched towards Rome with unwavering determination, announcing to every town they passed that they meant no harm – they were bound for Rome.

The battle for Rome unfolded near the Tiber and Allia rivers. The Gauls appeared to have a slight numerical advantage. The Roman commanders, likely a group of Tribunes, decided to place a reserve force on a nearby hill, hoping to counter-flank the Gauls if they broke through the Roman center or enveloped the wings. However, Brennus, the Gaulish leader, saw through this strategy and sent a force directly at the Roman hilltop reserves. The surprised Romans quickly fled.

The rest of the battle was a catastrophe for the Romans, who seemingly panicked at the sight of this formidable enemy. Many Romans scattered to the recently conquered Veii, others fled to Rome, while many drowned trying to cross the river in their armor. The Gauls were astonished by the ease of their victory.

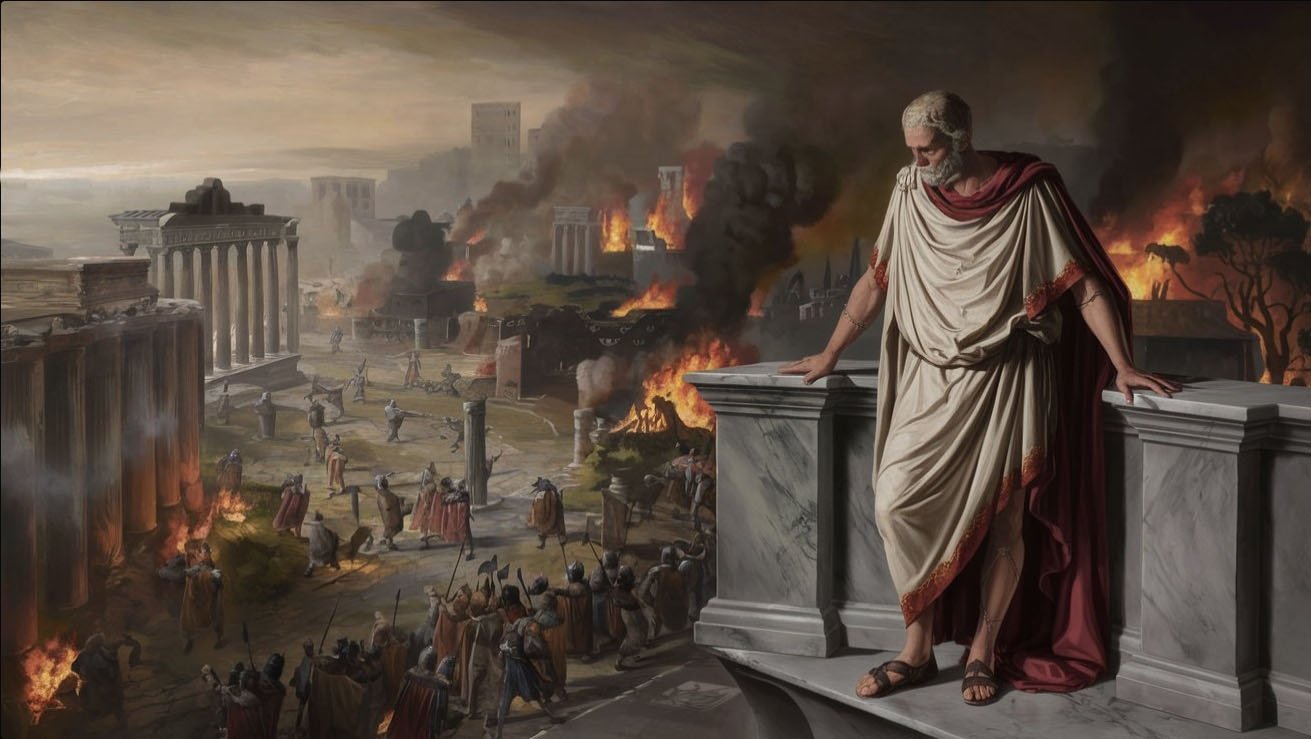

Rome, despite controlling only a few dozen miles around the city, had nonetheless built a powerful reputation throughout Italy – but was now vulnerable. It took the Gauls just a day to reach Rome, and they were again surprised by how lightly defended it was. The light defense was due to the sheer panic following the battle, with only a small portion of the survivors making it back to Rome. People fled to nearby cities or the countryside, and many priests and priestesses took their religious artifacts out of the city. Those who remained fortified the steep Capitoline Hill, preparing for the worst.

The Gauls stormed the city walls and rampaged through the city. They soon realized that the bulk of the remaining inhabitants were entrenched in the tall Capitoline hill and promptly attacked, full of confidence from their earlier victories. For the first time, the Romans effectively fought back, easily holding the high ground.

Brennus’s assault was a complete disaster, so he opted to lay siege to the hill instead, sending his men out to forage for supplies. During one of these foraging missions, they clashed with the exiled Camillus, who had organized a resistance from a nearby town.

The Roman senate, trapped on the besieged Capitoline hill, decided to restore the exiled Camillus to his command and grant him dictatorial powers. A daring messenger snuck through the Gallic camp and scaled the unguarded cliffside to deliver the message.

However, Brennus’s scouts discovered the messenger’s footprints and realized there was a way to scale the cliffs. They chose a night with a full moon and sent their bravest warriors up the cliff. Their ascent was so quiet and skillful that neither the Roman sentries nor their dogs noticed anything – but the geese did.

Juno’s sacred geese, well cared for despite the dwindling food, began quacking and honking relentlessly, waking some of the sleeping Romans. The first to respond was a man named Manlius. Without hesitation, Manlius charged at the Gauls as they reached the top of the cliff, killing one and pushing another off with his shield. Soon, other Romans joined the fight and killed the remaining Gauls as they came up. Other Gauls still clinging to the rocks below were helpless as the Roman defenders threw javelins and rocks at them until they fell to their death.

After this battle the Gauls, also suffering from disease and food shortages, agreed to accept a huge payment to withdraw from Rome. As the Romans loaded gold onto the scales, they noticed that the Gauls were rigging the weights to make the Romans pay more than was agreed. Brennus added to the Roman humiliation by placing his sword on with the Gallic weights and said the famous words “Vae victis” meaning “woe to the vanquished/conquered”, words that the Romans would take to heart. Successive generations would ensure that they never heard those words again.

Just as the delivery of gold was almost complete the Dictator Camillus appeared on the scene. As dictator, he declared the gold deal void and demanded that the Gauls leave immediately. Camillus told the Romans that they would win back their city through fighting, not by gold.

The Gauls were furious at the denial of the gold that they were so close to acquiring and marched out to attack Camillus’ newly formed army comprised of the survivors of the earlier battle at Allia and many new volunteers. The Romans under the skilled command of Camillus won an easy victory and attacked the retreating Gauls, sacking their camp and killing almost every Gaul.

The sack of Rome was a humiliating and traumatic event for the Romans, but it also served as a catalyst for change. In the aftermath, Rome rebuilt its defenses, including the construction of the Servian Wall, and reformed its military strategies. The city emerged stronger and more resilient, determined never to suffer such a defeat again. Indeed, it would be almost 800 years before Rome would fall again, this time to the Alaric’s Visigoths who would conquer the whole city, including the Capitoline hill.