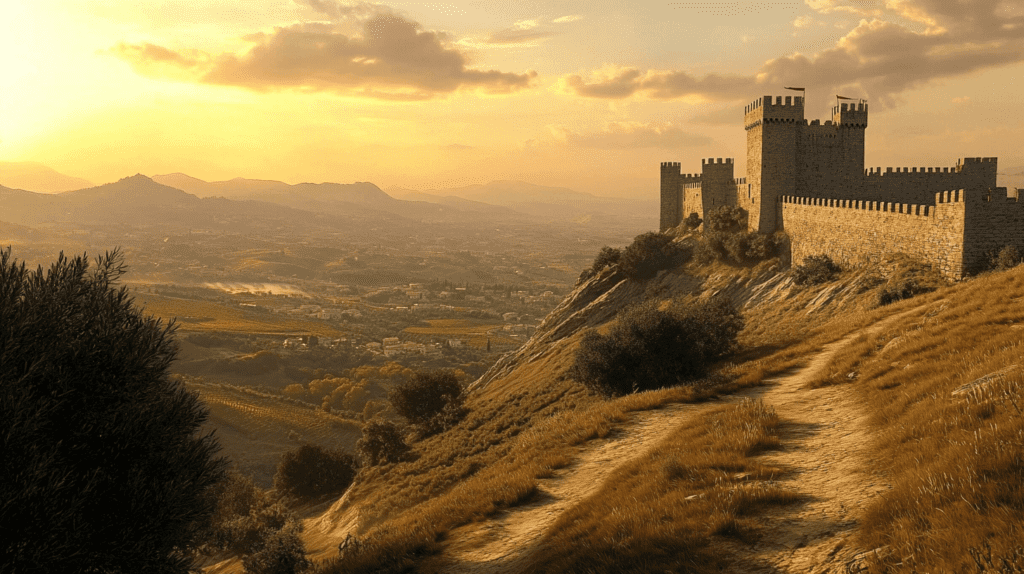

Origins of the Normans

The Normans originated from the Viking settlers who arrived in the region of Normandy in the early 10th century. These Norsemen, having adopted the local Frankish culture and Christianity, transformed into a formidable military power. By the 11th century, the Normans had begun to extend their influence beyond their homeland, driven by a desire for land, wealth, and adventure. The Norman conquest of southern Italy lasted from 999 to 1194, involving many battles and independent conquerors.

Early Incursions into Italy

The first significant Norman presence in Italy can be traced to the early 1040s when bands of mercenaries, known as the “Norman adventurers,” began to arrive in the southern Italian region, which was fragmented into various principalities and territories. The political instability created by the ongoing conflicts between the Byzantine Empire, the Papacy, and local lords provided an opportune environment for these ambitious warriors.

In contrast to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, which resulted from a single decisive battle within a few years, the conquest of southern Italy unfolded over several decades and involved numerous battles, few of which were truly decisive. Many territories were initially conquered independently and only later came together to form a unified state. While the conquest of southern Italy was more unplanned and disorganized compared to that of England, it was equally thorough in its outcome.

The Conquest of Apulia and Calabria

In 1024, Norman mercenaries under the command of Ranulf Drengot found themselves entwined in the tumultuous politics of southern Italy, serving Guaimar III alongside Pandulf IV in their relentless siege of Pandulf V in Capua. After an arduous 18-month standoff, Capua finally capitulated in 1026, restoring Pandulf IV to his princely throne. In the subsequent years, Ranulf aligned himself closely with Pandulf, but by 1029, he shifted his allegiance to Sergius IV of Naples, a move that followed the latter’s expulsion from Naples in 1027, a campaign likely aided by Ranulf himself.

In 1029, Ranulf and Sergius successfully recaptured Naples. By early 1030, Sergius granted Ranulf the County of Aversa as a fief, a title long considered the first Norman lordship in southern Italy—though modern historians now argue that the honor belongs to the County of Ariano, recognized by Emperor Henry II as early as 1022. The bond between Sergius and Ranulf deepened with the latter’s marriage to Sergius’s sister, the widow of the duke of Gaeta. Tragically, in 1034, she passed away, prompting Ranulf to return to the fold of Pandulf.

As Amatus recounts, the Normans were ever wary of the Lombards gaining a decisive edge, skillfully balancing their support between factions to avoid complete ruin for any side. Reinforced by local miscreants, who found a home among Ranulf’s ranks with no questions asked, the Norman presence burgeoned. Amatus observed how the distinct Norman language and customs began to forge a sense of unity among this disparate group.

In 1035, the same year William the Conqueror ascended to the Duchy of Normandy, three of Tancred of Hauteville’s sons—William “Iron Arm,” Drogo, and Humphrey—arrived in Aversa, marking a pivotal moment in the Norman expansion. By 1037, or possibly 1038, Norman influence was solidified when Emperor Conrad II deposed Pandulf and invested Ranulf as Count of Aversa. Ranulf’s ambition swelled further as he launched an invasion of Capua in 1038, vastly enlarging his territorial control across southern Italy.

That same year, Byzantine Emperor Michael IV mounted a military campaign into Muslim Sicily, deploying General George Maniaches against the Saracens. Among the forces, commanded by future Norwegian king Harald Hardrada, were 300 Norman knights sent by Guaimar IV of Salerno, including the illustrious Hauteville brothers. William earned his moniker, “Bras-de-Fer,” for his audacious single-handed slaying of the emir of Syracuse during the siege of that city. However, the Norman contingent withdrew prematurely, disenchanted by the poor distribution of the spoils.

The tides of conflict shifted further in 1040, following the assassination of Catapan Nikephoros Dokeianos. The Normans, seizing the moment, elected Atenulf, brother of Pandulf III of Benevento, as their leader. On March 16, 1041, near Venosa, they attempted negotiations with Catapan Michael Dokeianos, only to engage in battle, ultimately emerging victorious at Olivento. On May 4, the Normans, led by William Iron Arm, triumphed once more against Byzantine forces at Montemaggiore, avenging their earlier defeat in 1018.

By September 3, 1041, at the Battle of Montepeloso, the Normans, nominally under the command of Arduin and Atenulf, bested the Byzantine catepan Exaugustus Boioannes, taking him prisoner. At this juncture, Guaimar IV began to consolidate his hold over the Normans.

The initial Lombard rebellion had transformed under Norman leadership and character. In September 1042, the principal Norman leaders convened at a council in Melfi, attended by Ranulf, Guaimar IV, and William Iron Arm. They sought recognition for their conquests, with William proclaimed the leader of the Normans in Apulia, receiving the title of Count of Apulia from Guaimar. The latter, while declaring himself Duke of Apulia and Calabria, never secured formal recognition from the Holy Roman Emperor.

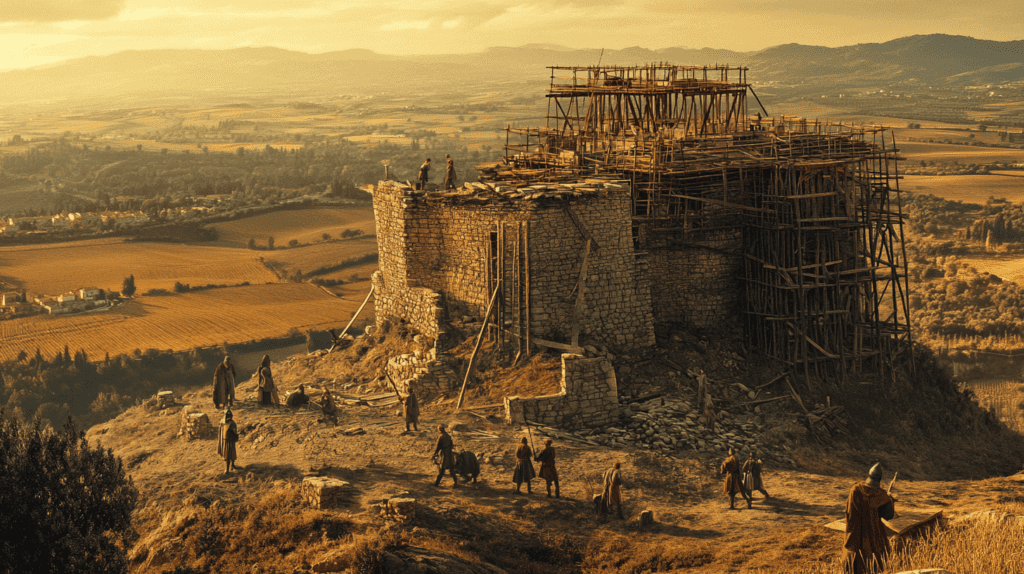

By 1043 at Melfi, Guaimar divided the region into twelve baronies for the Norman leaders, granting William control over Ascoli, while other leaders received their own territories. Together, they began the conquest of Calabria in 1044, fortifying their position by constructing the castle of Stridula. Yet, William faced setbacks in Apulia, notably suffering a defeat in 1045 near Taranto at the hands of Argyrus, although his brother Drogo succeeded in conquering Bovino.

William’s death marked a turning point, concluding the era of Norman mercenary service and heralding the emergence of two principalities under nominal allegiance to the Holy Roman Empire: the County of Aversa—later the Principality of Capua—and the County of Apulia, which would evolve into the Duchy of Apulia.

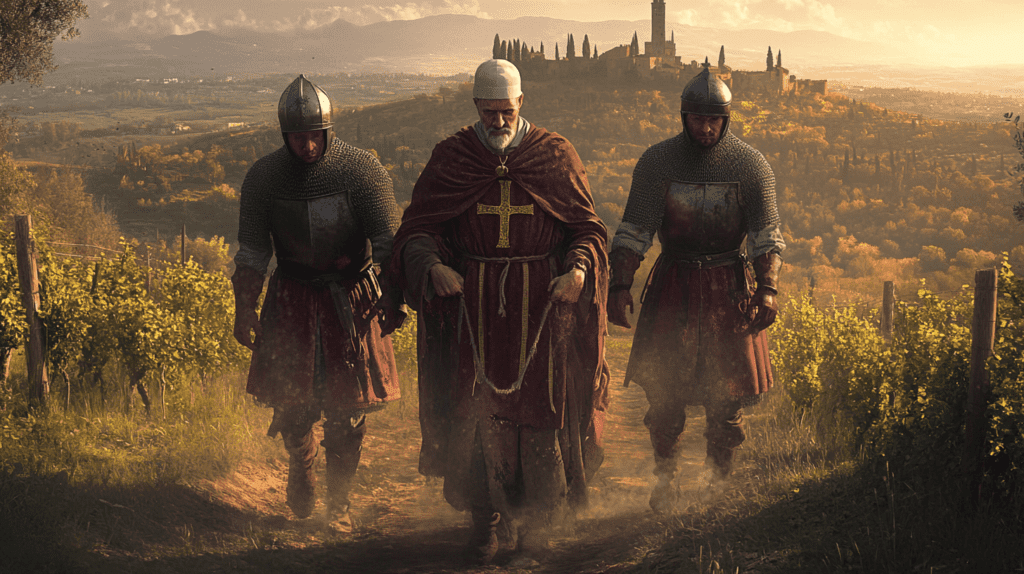

The Norman advances in southern Italy had long been a source of concern for the papacy, casting a shadow over its own ambitions in the region. The catalyst for the ensuing conflict, however, was rooted in a complex web of grievances. Foremost among these, was the deep-seated resentment felt by many local Italians, who viewed the Normans not merely as disruptors of the power balance but as ruthless marauders. The brutal raiding tactics employed by the Normans had incited a fierce desire for retribution among the populace, who regarded them as little more than brigands encroaching upon their lands and livelihoods.

The spectre of Norman power loomed large over southern Italy, prompting unease among the region’s Italian and Lombard rulers. Prince Rudolf of Benevento, the Duke of Gaeta, the Counts of Aquino and Teano, alongside the Archbishop and citizens of Amalfi, rallied together with Lombards from Apulia, Molise, Campania, Abruzzo, and Latium in response to the papal call to arms. This formidable coalition, comprised of forces from nearly every significant Italian magnate in the region.

The Pope also found another ally in the Byzantine Empire, ruled by Constantine IX. Initially, the Byzantines, who had established a presence in Apulia, sought to co-opt the Normans into their own mercenary ranks, leveraging the Normans’ notorious avarice. The Lombard Catepan of Italy, Argyrus, attempted to entice the Normans with promises of gold to serve on the Eastern frontiers. However, the Normans, their ambitions firmly set on the conquest of southern Italy, spurned the offer; Argyrus turned to the Pope. As Leo mobilized his forces from Rome to engage the Normans, Argyrus assembled a Byzantine army to join the fray, positioning both armies to converge on their quarry.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, the Normans hastily gathered their available men, uniting under a single banner led by Humphrey of Hauteville, the newly appointed Count of Apulia and the eldest surviving brother of Drogo. He was joined by Richard Drengot, Count of Aversa, and other members of the de Hauteville family, including the ambitious Robert, who would later earn the legendary title of Robert Guiscard. In this crucible of conflict, the stage was set for a decisive confrontation that would determine the fate of southern Italy.

The Battle of Civitate

Pope Leo moved his forces toward Apulia, reaching the banks of the Fortore River near the town of Civitate (or Civitella, northwest of Foggia). The Normans, aware of the strategic imperative to intercept the Papal army and prevent its union with the Byzantine forces under Argyrus, prepared for confrontation. Yet, they were beset by challenges: the harvest season had left them low on supplies, and their ranks were outnumbered — approximately 3,000 horsemen and 500 infantry stood against a coalition of 6,000 from the Papal and Byzantine forces. Both Amatus and William of Apulia paint a grim picture of the Norman plight, depicting troops so starved that they resorted to foraging, rubbing grains between their hands to extract the kernels.

The two armies faced each other, separated by a modest hill. The Normans arranged their cavalry into three distinct formations: Richard of Aversa commanded the heavy cavalry on the right; Humphrey led the infantry, dismounted knights, and archers in the center; while Robert Guiscard positioned himself with his own cavalry and the Slavic infantry on the left. Among their ranks were notable commanders like Peter and Walter, sons of Amicus, as well as Count Hugh and Count Gerard, who rallied the Beneventans and the men of Telese, respectively, and Count Radulfus of Boiano.

Facing them, the Papal army was divided into two segments. The Swabian infantry formed a thin, elongated line extending from the center to the right, while the Italian levies, commanded by Rudolf, amassed chaotically on the left. Although Pope Leo remained in Civitate, his standard — the vexillum sancti Petri — was present with his allied forces.

The battle commenced with Richard of Aversa launching a flanking charge against the Italians on the left. Their swift advance sent the Italian troops into disarray, many fleeing before even engaging in combat. The Normans pursued, inflicting heavy casualties as they pressed toward the Papal encampment.

Meanwhile, the Swabians advanced to the hill, engaging the Norman center led by Humphrey. A skirmish erupted, arrows flying as the two forces clashed in a fierce melee. The engagement predominantly unfolded on foot; the Swabians, renowned for their courage yet lacking equestrian skill, fought bravely with swords rather than lances. As William of Apulia noted, their long and keen blades often cleaved opponents in two, and they preferred to fight on foot, resolutely facing death rather than retreat.

As the battle raged, the Normans endeavored to flank the Swabians while Humphrey held his ground. Seeing his brother in peril, Robert Guiscard moved to reinforce the left wing, alleviating the pressure on the Norman center with the support of the Calabrians led by Count Gerard.

The situation in the center remained precarious, yet the steadfast discipline of the Normans ultimately turned the tide. The return of Richard’s forces from their pursuit of the fleeing Italians proved decisive, leading to the rout of the Papal coalition.

In the aftermath, the Normans prepared a siege of Civitate itself, capturing Pope Leo in the process. Accounts of his capture diverge: some papal sources claim Leo voluntarily surrendered to spare further bloodshed, while others, including Malaterra, assert that the citizens of Civitate expelled him in fear of the advancing Norman threat. Regardless, Leo was treated with respect during his captivity in Benevento, held for nearly nine months and compelled to ratify treaties favorable to the Normans.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine forces, facing the collapse of their ambitions, disbanded and retreated to Greece, potentially leaving Argyrus himself in disgrace. The Battle of Civitate marked a pivotal turning point for the Normans, who not only secured victory against overwhelming odds but also solidified their legitimacy in Italy. For Robert Guiscard, it heralded the beginning of his rise as a formidable leader among the Normans.

The implications of this battle echoed far beyond the immediate conflict, paralleling the transformative impact of the Battle of Hastings in England. The balance of power shifted, reorienting the landscape of Latin Christendom. In his efforts to maintain an anti-Norman coalition with the Byzantines, Leo’s failure to negotiate effectively and his subsequent death extinguished any hope of substantial support from the East. Thus, the schism between Rome and Constantinople inadvertently benefitted the Normans, allowing them to consolidate their power unimpeded.

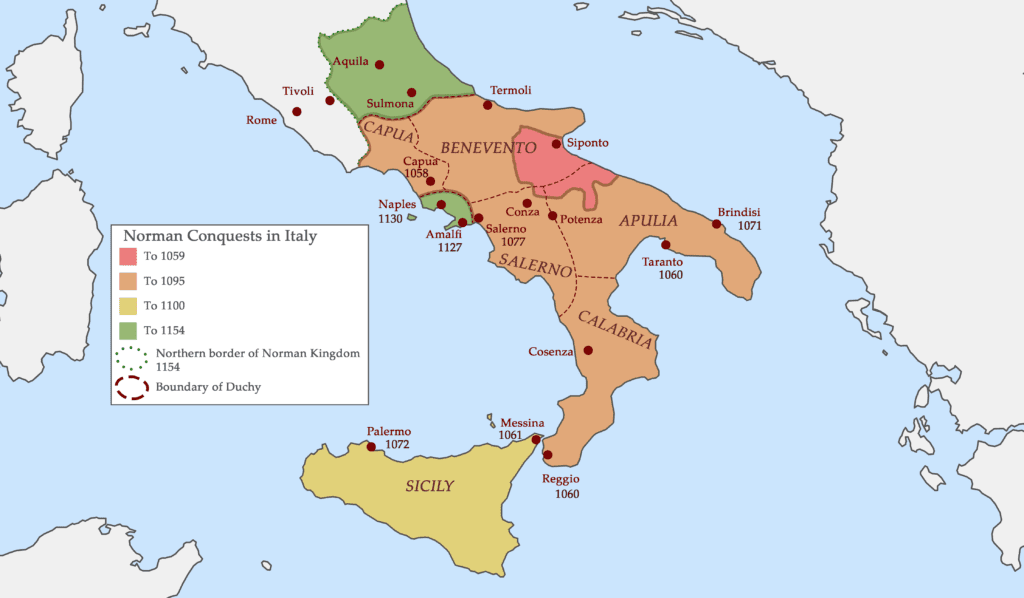

Ultimately, after six tumultuous years and the tenure of three anti-Norman popes, the Treaty of Melfi in 1059 recognized the Normans as a legitimate force in southern Italy. This shift in papal politics stemmed from a growing realization: the Normans, once seen as a threat, had emerged as a powerful, proximate ally, while the Holy Roman Emperor had become a distant, ineffective supporter. Pope Nicholas II’s decision to sever ties with imperial authority, reclaiming the right of Roman cardinals to elect the pope, underscored the changing dynamics. In the face of the Empire’s weakness, the Normans’ newfound strength proved indispensable in the ongoing struggle for dominance in the region.

Conquest of Sicily, 1061–1091

In May 1061, Robert Guiscard and his younger brother Roger launched their audacious invasion of Sicily, crossing the Strait of Messina from Reggio di Calabria with a singular objective: to seize control of this strategically crucial passage. Under the cover of night, Roger crossed the strait, landing undetected and springing a surprise attack on the Saracen forces at dawn. When Robert’s troops followed suit later that day, they found the city of Messina abandoned and vulnerable. Seizing the opportunity, Robert quickly fortified the settlement and forged an alliance with the local emir, Ibn al-Timnah, to counter the influence of his rival, Ibn al-Hawas.

Together, Robert, Roger, and Ibn al-Timnah advanced into the heart of Sicily via Rometta, a town that had remained loyal to their newfound ally. Their march took them through Frazzanò and across the vast Pianura di Maniace, where they faced resistance during their assault on Centuripe. However, Paternò fell swiftly to their onslaught, and Robert pressed on to Castrogiovanni (modern Enna), the island’s strongest fortress. Despite a decisive defeat of the garrison, the citadel itself withstood their siege. With winter approaching and the threat of attrition looming, Robert opted to withdraw to Apulia, but not before constructing a fortress at San Marco d’Alunzio to solidify his foothold.

Roger remained in Sicily, returning in late 1061 to capture Troina. In June 1063, he secured a significant victory against a Muslim army at the Battle of Cerami, further entrenching the Norman presence on the island.

In August 1071, the Normans launched a determined and ultimately successful siege of Palermo. By 7 January 1072, they had breached the city’s defenses, and just three days later, the beleaguered defenders of the inner city surrendered. In the wake of this victory, Robert conferred the title of Count of Sicily upon Roger, recognizing his authority under the suzerainty of the Duke of Apulia. In a strategic division of the island, Robert retained control of Palermo, half of Messina, and the predominantly Christian region of Val Demone, leaving Roger with the rest, including the yet unconquered territories.

By 1077, Roger turned his sights on Trapani, one of the last bastions of Saracen power in western Sicily. His son, Jordan, executed a daring sortie that caught the guards of the garrison’s livestock off guard. With their food supplies cut, Trapani soon capitulated. The following years saw Roger continue his campaign: in 1079, he besieged Taormina, and by 1081, a coordinated assault led by Jordan, Robert de Sourval, and Elias Cartomi resulted in the surprise capture of Catania, a stronghold of the emir of Syracuse.

In the summer of 1083, Roger temporarily left Sicily to aid his brother on the mainland, only to be forced back when Jordan revolted, compelling him to reassert control over his rebellious son. By 1085, Roger embarked on a systematic campaign to secure the island. On 22 May, he approached Syracuse by sea, while Jordan led a cavalry detachment north of the city. On 25 May, a naval battle was fought in the harbor, resulting in the death of the emir. Meanwhile, Jordan’s forces besieged Syracuse itself. The siege stretched through the summer, and when the city finally surrendered in March 1086, only Noto remained under Saracen control. That stronghold too fell in February 1091, marking the complete conquest of Sicily.

In the same year, Roger turned his attention to Malta, swiftly subduing the fortified city of Mdina. He imposed taxes but allowed the Arab governors to maintain their rule, demonstrating a pragmatic approach to governance. It wasn’t until 1127, under Roger II, that the Muslim administration was abolished, replaced by Norman officials.

Conquest of Naples, 1077–1139

The Duchy of Naples, though technically a Byzantine territory, was one of the last southern Italian states to face Norman aggression. Since Sergius IV sought help from Ranulf Drengot in the 1020s, the dukes of Naples largely aligned with the Normans of Aversa and Capua, save for brief intervals. It took sixty years, starting in 1077, for Naples to be fully absorbed into the Hauteville realm.

In the summer of 1074, tensions erupted between Richard of Capua and Robert Guiscard. Sergius V of Naples allied with Guiscard, turning Naples into a key supply hub. This brought him into conflict with Richard, who had the backing of Pope Gregory VII. Richard briefly besieged Naples in June, but negotiations soon followed, mediated by Desiderius of Montecassino.

By 1077, Richard resumed the siege with naval support from Guiscard. His death during the siege in 1078, after his excommunication was lifted, led his successor, Jordan, to end the siege to improve relations with the papacy.

In 1130, Antipope Anacletus II crowned Roger II of Sicily as king, declaring Naples part of his domain. By 1131, after Amalfi’s resistance was crushed, Sergius VII of Naples submitted to Roger, intimidated by Amalfi’s fall. Chronicler Alexander of Telese remarked that Naples, unconquered since Roman times, fell without a fight.

Sergius supported a rebellion against Roger in 1134 but avoided direct conflict, paying homage after Capua’s fall. In 1135, a Pisan fleet arrived in Naples, making the duchy the center of resistance. Naples was besieged until 1136, when Emperor Lothair II’s army arrived, lifting the siege. However, Sergius soon re-submitted to Roger. Sergius died in 1137 at the Battle of Rignano, marking the end of Neapolitan independence. Though it took two more years for Naples to be fully absorbed into Roger’s kingdom, his son Alfonso was eventually recognized as duke in 1139. All of Southern Italy was now Norman land.