In the annals of English history, few monarchs have left as indelible a mark as King Æthelstan, yet his name often fails to resonate with the same familiarity as those of Alfred the Great or William the Conqueror. Born around 894 AD, Æthelstan would go on to become the first king to unite the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, earning him the title of the first true King of England. His reign, though relatively short, was pivotal in shaping the foundations of the English nation.

Early Life and Ascension to the Throne

Æthelstan was born into the royal House of Wessex, the grandson of the legendary Alfred the Great and son of Edward the Elder. His early years were marked by an unconventional upbringing that would later prove instrumental to his success. While his father ruled Wessex, young Æthelstan was raised in the Mercian court of his aunt, Æthelflæd, known as the “Lady of the Mercians”.

This unique childhood provided Æthelstan with a broad perspective on the diverse kingdoms that would eventually form his realm. Under the tutelage of his aunt, a formidable ruler in her own right, he learned the intricacies of statecraft and military strategy that would serve him well in his future role.

The path to Æthelstan’s kingship was not without its challenges. When his father, Edward the Elder, died in 924, the succession was initially disputed. Æthelstan’s half-brother, Ælfweard, was briefly recognized as king in Wessex. However, fate intervened when Ælfweard died just 16 days after their father, clearing the way for Æthelstan’s ascension.

Even then, Æthelstan faced resistance, particularly from Wessex. It wasn’t until September 925 that he was finally crowned at Kingston upon Thames, a symbolic location on the border between Wessex and Mercia. This coronation marked a significant moment in English history, as it was the first time a king wore a crown instead of a helmet during the ceremony, signifying a shift from warrior kingship to a more regal and centralized form of rule.

Unification of England

Æthelstan’s most significant achievement was the unification of England under a single crown. This process, begun by his predecessors, reached its culmination during his reign. In 927, following the death of his brother-in-law Sihtric, the Viking ruler of Northumbria, Æthelstan seized the opportunity to conquer York, the last remaining Viking kingdom in England.

This conquest was a watershed moment. On July 12, 927, at a gathering near Penrith, King Constantine of Scotland, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, and King Owain of Strathclyde all submitted to Æthelstan, acknowledging him as their overlord. This event marked the birth of England as a unified political entity, with Æthelstan as its first true king. England’s existence would be threatened within seven years.

Military Prowess and the Battle of Brunanburh

In the summer of 934, Æthelstan set his sights on Scotland. The peace that had reigned since 927, when he had forced the submission of various British kings at Eamont, near Penrith, was about to be shattered. The reasons for this sudden aggression remain shrouded in mystery, though John of Worcester claimed it was due to Constantine’s violation of their treaty established seven years previously.

The invasion of Scotland was a two-pronged assault. While the army harried the Scottish lowlands, penetrating as far as Kincardineshire, the fleet terrorized the coastline, reaching the distant shores of Caithness. Yet for all its sound and fury, Æthelstan’s campaign failed to provoke a decisive engagement.

As the English withdrew, leaving behind a Scotland bloodied but unbroken, a new threat was already taking shape. Æthelstan’s enemies, long divided by ancient feuds and conflicting interests, began to realize that only through unity could they hope to challenge the English king’s growing hegemony.

In Dublin, Olaf Guthfrithson, the Viking king of the city, emerged as the catalyst for this unprecedented alliance. He found willing partners in Constantine II of Scotland and Owen of Strathclyde, both smarting from their recent humiliations. That these former foes could set aside their differences spoke volumes about the perceived threat posed by Æthelstan.

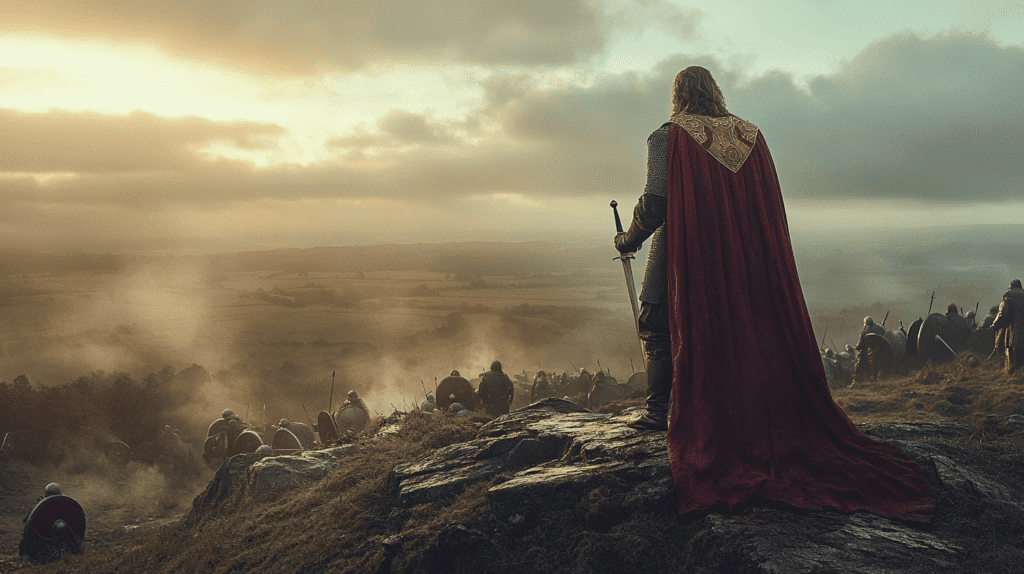

By August 937, the pieces were in place. Olaf’s fleet set sail from Dublin, laden with hardened Norse warriors. As they approached the shores of Britain, Constantine and Owen marshaled their forces. The stage was set for a confrontation that would determine the fate of Britain.

Æthelstan, ever the astute commander, did not remain idle. As reports of the invasion reached him, he moved swiftly to rally his forces. Saxon troops were hastily mustered from Mercia as the king marched north to meet this unprecedented threat. The two great armies converged, each knowing that the future of Britain hung in the balance.

The battle raged from dawn to dusk, a brutal test of will and martial skill. The English forces, hardened veterans of countless skirmishes, found themselves locked in a desperate struggle against the combined might of the northern alliance. The air was thick with the clash of steel on steel, the dull thud of axe on shield, and the cries of the wounded and dying.

As the day wore on, the battlefield became a hellish landscape of mud, blood, and broken bodies. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle paints a vivid picture of the carnage: “They clove the shield-wall, hacked the war-lime, with hammers’s leavings”. The ground was littered with the fallen, Norse and Scots alike, “shot over shield, taken by spears… sated, weary of war”.

Finally, as the sun began to dip towards the horizon, the northern alliance’s resolve crumbled. What began as an orderly retreat quickly devolved into a rout. Æthelstan, sensing victory, urged his men forward in a relentless pursuit. The fleeing invaders were cut down in droves, their bodies marking a grim trail across the countryside.

Olaf Guthfrithson, the architect of the alliance, managed to escape the slaughter. With the remnants of his once-mighty army, he fled to the coast and set sail for Dublin, leaving behind the broken dreams of conquest. Constantine of Scotland, too, managed to slip away, though at a terrible cost. His son lay among the dead, a stark reminder of the day’s butcher’s bill.

The scale of the carnage was unprecedented. The Annals of Ulster described the battle as “great, lamentable and horrible”, with thousands of Norsemen falling to English steel. Five kings and seven earls from Olaf’s army were counted among the slain. Even the victorious English paid a heavy price, with two of Æthelstan’s cousins, Ælfwine and Æthelwine, numbered among the fallen.

As night fell on the blood-soaked field of Brunanburh, the magnitude of the English victory became clear. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, with perhaps a touch of poetic license, declared that never had there been such slaughter since the days when the Angles and Saxons first came to Britain’s shores. Æthelstan stood triumphant, having shattered the northern alliance and secured his position as the dominant power in Britain. Æthelstan’s victory prevented the dissolution of England, but it failed to unite the island: Scotland and Strathclyde remained independent.

Governance and Legal Reforms

Æthelstan’s reign was marked by significant advancements in governance and law. He centralized the system of government, establishing a network of royal officials responsible for collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and maintaining order throughout the kingdom.

His court became the center of administration, with bishops, ealdormen (high-ranking law enforcers), and local magnates routinely assembling for the king’s councils. These gatherings, which discussed matters of state and took stock of the realm, have been described as a rudimentary form of parliament.

Æthelstan built upon the legal reforms of his grandfather, Alfred the Great, issuing numerous law codes that reveal his concern for social order and justice. He was particularly focused on combating the threat of robbery and lawlessness. His laws show a remarkable degree of sophistication for the time, including provisions for more lenient treatment of young offenders.

One of Æthelstan’s most notable legal innovations was the concept of “single monarchy” – the idea that he alone had the right to mint coins, issue laws, and grant land throughout all of England. This was a crucial step in establishing a centralized, unified state.

Diplomacy and European Relations

Æthelstan’s influence extended far beyond the shores of Britain. He was keenly aware of England’s place in the broader European context and worked tirelessly to elevate its status on the continental stage.

His approach to foreign relations was multifaceted. He arranged marriages between his sisters and various European rulers, forging closer ties between England and the continent. One of his sisters, Edith, was married to Otto, son of Henry the Fowler, who would later become Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great.

Æthelstan’s court became a haven for exiled princes and nobles from across Europe. Among his foster-children were Alan of Brittany, who would later become Duke of Brittany, and Haakon, son of Harald Fairhair of Norway, who would eventually return to become King of Norway.

These connections not only enhanced England’s prestige but also facilitated cultural exchange. Æthelstan’s court became a melting pot of ideas, with scholars and clerics from across Europe contributing to the intellectual life of the kingdom.

Cultural and Religious Patronage

Æthelstan was renowned for his piety and his patronage of the church and monasteries. He was a prolific founder of churches and a dedicated collector of holy relics. His religious devotion was not merely personal; it was a key aspect of his kingship and his vision for a unified England.

Under Æthelstan’s rule, monasteries became centers of learning and culture. He encouraged the production of manuscripts, and many of the most beautiful examples of Anglo-Saxon art and literature date from his reign. The famous “Æthelstan Psalter” is just one example of the exquisite craftsmanship fostered during this period.

Æthelstan’s court was also a center of learning. He assembled an impressive library, unusual for a layman of his time, and encouraged the translation of Latin texts into Old English. This promotion of vernacular literature was crucial in developing a distinct English cultural identity.

Legacy and Historical Significance

When Æthelstan died on October 27, 939, in Gloucester, he left behind a kingdom vastly different from the one he had inherited. He was buried at Malmesbury Abbey, rather than with his father and brother at Winchester, perhaps reflecting his desire to be remembered as a king of all England, not just Wessex.

Æthelstan’s achievements were manifold. He unified England, established a system of centralized government, reformed the legal system, elevated England’s status in Europe, and fostered a renaissance in learning and culture. Yet, despite these accomplishments, his legacy has often been overshadowed by other Anglo-Saxon kings, particularly his grandfather Alfred.

This historical oversight is perhaps due to the brevity of his reign and the fact that his unification of England was temporarily undone after his death. The Vikings regained control of York, and it would take until 954 for the Anglo-Saxons to regain full control of England.

However, modern historians have come to recognize Æthelstan’s crucial role in English history. He is now generally regarded as the first true King of England and the father of medieval England. His reign laid the foundations for the nation that would emerge in the centuries to come.