In the annals of military history, few weapons have captured the imagination quite like Greek Fire. This incendiary substance, shrouded in mystery and legend, played a pivotal role in the Byzantine Empire’s defense for centuries. From its enigmatic origins to its devastating effects on the battlefield, Greek fire stands as a testament to Byzantine ingenuity and the power of technological superiority in warfare.

The Origins of Greek Fire

Greek fire first emerged in the 7th century AD, during a time of great peril for the Byzantine Empire. The empire, weakened by long wars with Sassanid Persia, faced an existential threat from the rapidly expanding Arab caliphate.

It was in this context that a weapon of unprecedented power was developed. The creation of Greek fire is traditionally attributed to Kallinikos (Latinized as Callinicus), a Jewish architect from Heliopolis in Syria. According to the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, Kallinikos fled to the Byzantine Empire around 672 AD, bringing with him the secret of this powerful weapon.

Composition and Properties

The exact composition of Greek fire remains one of history’s enduring mysteries. Byzantine emperors guarded the secret jealously, passing it down from generation to generation. This secrecy was so complete that even today, scientists struggle to recreate the formula precisely. What we do know about Greek fire is that it possessed several remarkable properties:

- It could burn on water, making it particularly effective in naval warfare.

- The fire produced was difficult to extinguish, reportedly only yielding to a mixture of vinegar, sand, and old urine.

- When deployed, it created a loud roar and thick smoke, adding a psychological element to its physical destructiveness.

While the exact ingredients remain unknown, historical sources and modern speculation suggest a mixture that may have included petroleum, quicklime, sulfur, and pine resin.

Deployment and Tactics

The Byzantines developed sophisticated methods for deploying Greek fire, which contributed significantly to its effectiveness. The primary delivery system was the siphon, a pump mechanism mounted on ships that could project the liquid fire at enemy vessels. In addition to ship-mounted siphons, the Byzantines also developed handheld devices called cheirosiphons for use in land battles and siege warfare. These versatile weapons allowed Byzantine forces to employ Greek fire in a variety of tactical situations.

Impact on Byzantine Military Strategy

The introduction of Greek fire fundamentally altered the balance of power in the Mediterranean. It provided the Byzantine Empire with a crucial technological edge, particularly in naval warfare. The weapon’s effectiveness allowed the Byzantines to maintain control over vital sea lanes and defend their capital, Constantinople, against numerous sieges. The psychological impact of Greek fire cannot be overstated. Its terrifying effects often caused enemy forces to flee at the mere sight of its deployment. This fear factor made Greek fire an effective deterrent, sometimes allowing the Byzantines to achieve strategic objectives without actually using the weapon.

An example of Greek Fire in action: The Second Arab Siege of Constantinople (717-718 AD)

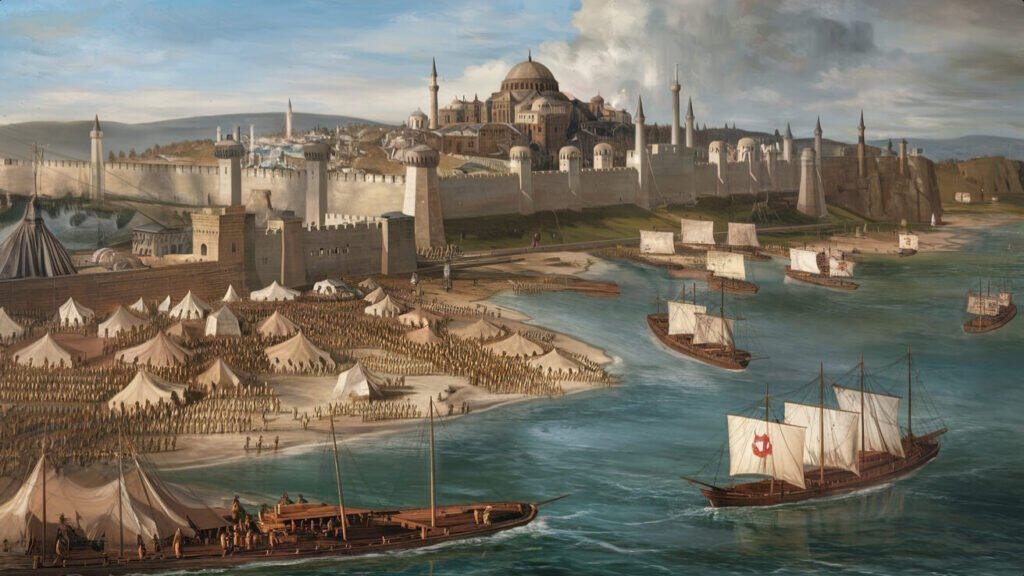

By 717, the Umayyad Caliphate had expanded rapidly, conquering much of the former Byzantine territory in the Middle East and North Africa. The caliph, Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, set his sights on the ultimate prize: Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The Arab forces, led by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik, were massive. Historical sources suggest an army of up to 120,000 men and a fleet of 1,800 ships. The Byzantines, under the newly crowned Emperor Leo III the Isaurian, faced a seemingly insurmountable challenge.

The Arab forces arrived at Constantinople in August 717, establishing a formidable blockade by land and sea. They were confident in their numerical superiority and expected a swift victory. However, they had not reckoned with the secret weapon of the Byzantines.

The Naval Assault

As the Arab ships approached the walls of Constantinople, the Byzantines unleashed their terrifying weapon. Ships equipped with siphons sprayed liquid fire onto the enemy vessels. The results were devastating. Eyewitness accounts describe scenes of horror as the unstoppable flames engulfed ship after ship. The fire spread rapidly across the water’s surface, creating an inferno that trapped Arab sailors. Many jumped overboard in panic, only to find that the flames continued to burn on the water’s surface. The psychological impact was immediate. The Arab forces, who had never encountered such a weapon, were thrown into disarray. Their carefully planned naval assault turned into a chaotic retreat as captains desperately tried to maneuver their ships away from the Byzantine fire ships.

The Tide Turns

The use of Greek fire not only repelled the initial naval assault but also created a lasting advantage for the defenders. The Byzantine fleet, emboldened by their secret weapon, was able to break the naval blockade and keep supply lines open to the Black Sea. This proved crucial as the siege dragged on into the winter months. On land, the Byzantines used handheld siphons to great effect, repelling Arab attempts to scale the city walls. The sight of their comrades engulfed in unquenchable flames demoralized the besieging forces.

The Aftermath

By the spring of 718, the Arab position had become untenable. A harsh winter, combined with a Bulgarian attack on their rear and the constant threat of Greek fire, had decimated their forces. In August 718, exactly one year after the siege began, the Arabs were forced to withdraw. The failure of the siege marked a turning point in history. It halted the westward expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate and preserved the Byzantine Empire as a bulwark of Christian civilization in the East. Greek fire had played a pivotal role in this world-changing victory.

Legacy and Decline

The success of Greek fire in defending Constantinople cemented its place in Byzantine military strategy for centuries. It was used effectively in numerous subsequent battles, including conflicts with the Rus’ in 941 and 1043, and against the Bulgarians in 970-971.

However, the very secrecy that made Greek fire so effective ultimately contributed to its decline. As the Byzantine Empire weakened in its later years, the closely guarded formula was lost. By the time of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, there are no reliable accounts of its use. In later centuries, various incendiary weapons were referred to as “Greek fire,” but these were likely different substances altogether. The true secret of Kallinikos’ invention remains lost to history.