Henry the Fowler’s Rise to Power

The early 10th century marked a pivotal moment in European history as the Carolingian dynasty’s grip on power in the East Frankish realm came to an end. This period of transition saw the emergence of a new ruling house – the Ottonians – led by Henry the Fowler, Duke of Saxony. The events that unfolded during this time would lay the foundation for the medieval German state and reshape the political landscape of Central Europe.

The Decline of the Carolingians

The Carolingian dynasty, established by Charlemagne, had ruled over vast swathes of Europe for over a century. However, by the early 900s, their power in the eastern part of the Frankish Empire was waning. The last Carolingian ruler of East Francia was Louis the Child, who ascended to the throne in 900 at the tender age of six.

Louis’s reign was marked by instability and external threats. The kingdom faced repeated invasions by the Magyars, a nomadic people from the east who wreaked havoc on the frontiers. Meanwhile, powerful nobles within the realm increasingly asserted their independence, weakening central authority.

On November 24, 911, Louis the Child died without an heir, bringing an end to Carolingian rule in East Francia. His death created a power vacuum that would need to be filled to maintain stability in the region.

The Interregnum and Conrad I

Following Louis’s death, the East Frankish nobles faced a critical decision. For the first time in over a century, there was no clear Carolingian successor to the throne. In this unprecedented situation, the dukes of Saxony, Swabia, and Bavaria convened at Forchheim to elect a new king.

Their choice fell upon Conrad of Franconia, who became Conrad I of Germany. This election marked a significant shift in the political dynamics of the region. Conrad, while related to the Carolingians through the female line, represented a new dynasty – the Conradines.

Conrad’s reign, however, was fraught with challenges. He struggled to assert his authority over the powerful dukes, particularly Henry of Saxony, who had become increasingly influential. Despite his efforts, Conrad was unable to fully consolidate his power or effectively address the ongoing Magyar threat.

The Rise of Henry the Fowler

As Conrad’s reign drew to a close, he made a decision that would have far-reaching consequences. On his deathbed in 918, Conrad recommended Henry of Saxony as his successor, bypassing his own brother Eberhard. This choice was a testament to Henry’s growing power and influence, as well as a pragmatic acknowledgment of the political realities of the time.

Henry, known as “the Fowler” due to his love of hunting birds, was the son of Otto the Illustrious, Duke of Saxony. He had inherited the Saxon duchy in 912 and had already proven himself an able ruler and military leader.

In 919, the Imperial Diet convened at Fritzlar to elect a new king. Following Conrad’s recommendation, the assembled Franconian and Saxon nobles chose Henry as their new ruler. This election marked the beginning of Saxon rule over the East Frankish kingdom and the foundation of what would become known as the Ottonian dynasty.

Henry’s Approach to Kingship

Henry’s ascension to the throne represented more than just a change in ruling families; it signaled a shift in the very nature of kingship in the East Frankish realm. Unlike his Carolingian predecessors, Henry did not seek to create a centralized monarchy. Instead, he viewed the kingdom as a confederation of stem duchies, with himself as first among equals (primus inter pares).

This approach was evident in Henry’s coronation. When Archbishop Heriger of Mainz offered to anoint him according to tradition, Henry refused – the only king of his time to do so. He stated that he wished to be king not by the church’s sanction, but by the people’s acclaim. This decision underscored Henry’s pragmatic approach to power and his recognition of the importance of secular support.

Consolidating Power

Henry’s initial position as king was precarious. While he had the support of the Saxons and Franconians, the dukes of Swabia and Bavaria did not initially recognize his authority. Henry set about consolidating his power through a combination of diplomacy and military action.

One of his first challenges came from Burchard II, Duke of Swabia. Henry managed to secure Burchard’s allegiance, demonstrating his diplomatic skills. When Burchard died, Henry appointed a Franconian noble as the new duke, further strengthening his position.

In Bavaria, Henry faced a more formidable opponent in Duke Arnulf. After two military campaigns, Henry succeeded in compelling Arnulf to submit to his authority and relinquish his claim to the German throne. In a shrewd move, Henry allowed Arnulf to retain significant control over his duchy’s internal affairs, thus securing his loyalty without completely subjugating him.

Expansion and Defense

With his position within the East Frankish kingdom secured, Henry turned his attention to expanding and defending his realm. In 925, he defeated Giselbert, the ruler of Lotharingia, and brought this important territory back under East Frankish control. To cement this alliance, Henry arranged for his daughter Gerberga to marry Giselbert.

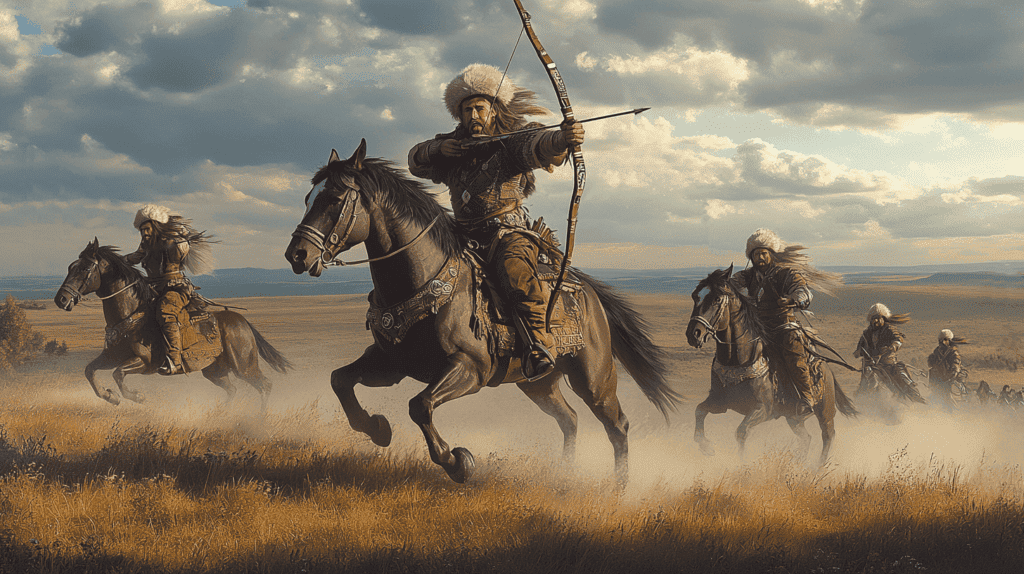

Perhaps the greatest threat to Henry’s kingdom came from the Magyars, who had been raiding German territories for years. In 924, facing a major Magyar invasion, Henry made a controversial decision. Unable to defeat the invaders militarily, he negotiated a nine-year truce, agreeing to pay them tribute in exchange for peace.

This truce proved to be a masterstroke of strategy. Henry used the respite to strengthen his kingdom’s defenses. He built a network of fortified towns and trained a new, mobile heavy cavalry force. When the Magyars resumed their attacks in 933, Henry was ready.

The Battle of Riade began when the Magyars had besieged an unknown town but attempted to withdraw upon learning of Henry’s nearby encampment. Henry initially sent forward a small contingent of foot soldiers with a few cavalrymen as a screen for his main army. When the main Magyar force engaged his vanguard, Henry countered with his light-armored troops. This was followed by a decisive charge of heavy cavalry. According to the chronicler Widukind of Corvey, the Magyar forces quickly fled after engaging Henry’s heavy cavalry. Victory effectively ending the Magyar threat for over two decades.

Building a Nation

Henry’s reign was characterized not just by military victories, but by nation-building efforts that laid the groundwork for the future German state. He encouraged the development of towns and cities, recognizing their importance for trade and defense. Cities like Brunswick, Lüneburg, and Lübeck flourished under his rule.

In the east, Henry expanded German influence through a series of campaigns against Slavic tribes. He conquered territories in Brandenburg and Meissen, establishing fortified settlements to secure these new frontiers. In 929, he quelled a rebellion in Bohemia, further extending his authority.

Henry’s policies fostered a sense of unity among the diverse peoples of his realm. His victories against external threats, particularly the Magyars, contributed to the emergence of a shared German identity. The Battle of Riade, in particular, is often seen as a pivotal moment in the formation of German national consciousness.

Legacy and Succession

When Henry died on July 2, 936, he left behind a kingdom that was stronger, more unified, and better defended than the one he had inherited. He was buried in Quedlinburg Abbey, which had been founded by his wife Matilda.

Henry’s greatest legacy, however, was his son and successor, Otto. Before his death, Henry had secured the nobles’ agreement to recognize Otto as the next king. Otto would go on to become Otto I, known as Otto the Great, the first Holy Roman Emperor of the Ottonian dynasty.

Under Otto and his successors, the foundations laid by Henry would be built upon to create the medieval German state. The Ottonian dynasty would rule for over a century, shaping the political and cultural landscape of Central Europe. Moreover, the sense of German identity that began to emerge during this time would play a crucial role in the long process of German unification that would unfold over the following millennium.