Origins and Early History

The Picts were not a single tribe, but rather a confederation of tribal units that allied against common enemies. While earlier theories suggested they arrived in Scotland shortly before their mention in Roman history, modern scholarship proposes a much earlier presence. Some experts argue that the Picts were, in fact, the indigenous population of northern Scotland.

The name “Picts” first appears in written records in 297 CE, used by the Roman writer Eumenius. He referred to the tribes of Northern Britain as “Picti,” meaning “the painted ones,” supposedly due to their practice of painting their bodies. However, this etymology has been contested by modern scholars. It’s more likely that they called themselves some form of “Pecht,” meaning “the ancestors”.

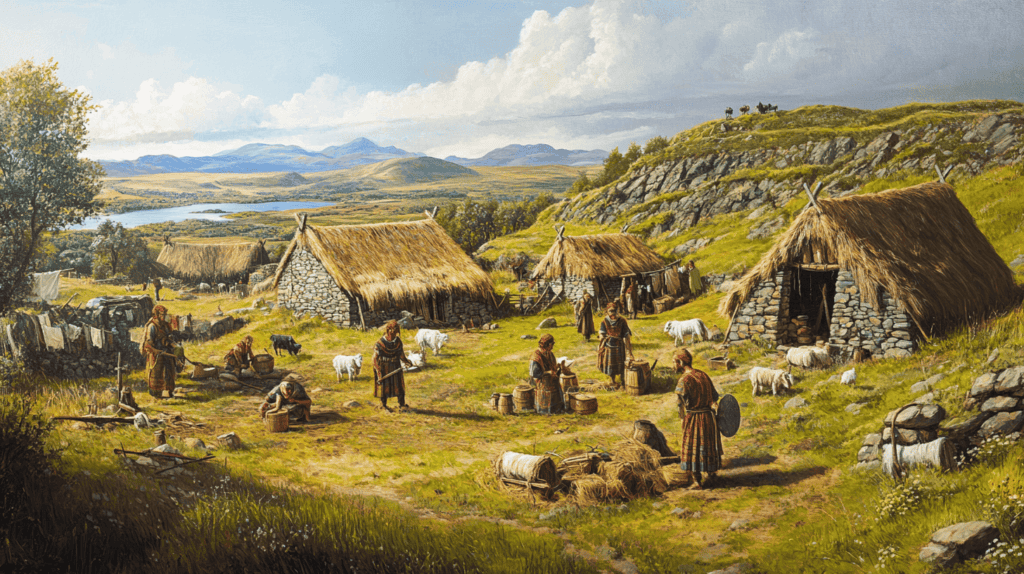

The Picts’ territory extended across northern Scotland, from Orkney in the north to the Firth of Forth in the south. They lived in small, tightly-knit communities, building their homes primarily from wood. Despite the perishable nature of their dwellings, the Picts left behind impressive stone carvings that provide valuable insights into their culture and history.

Society and Culture

Social Structure

Pictish society was organized into clans or “kins,” each led by a tribal chief. These clans included the Caerini, Cornavii, Lugi, Smertae, Decantae, Carnonacae, Caledonii, Selgovae, and Votadini. While these clans often acted independently, they would unite under a single leader when faced with external threats.

The role of the clan chief was pivotal in Pictish society. As described by historians Peter and Fiona Somerset Fry:

“The head of the kin was a very powerful man. He was looked upon as father of everyone in the kin, even though he might only be a distant cousin to most. He commanded their loyalty: he had proprietary rights over their land, their cattle; their possessions were in a sense his. His quarrels involved them and they had to take part in them, even to the point of laying down their lives”.

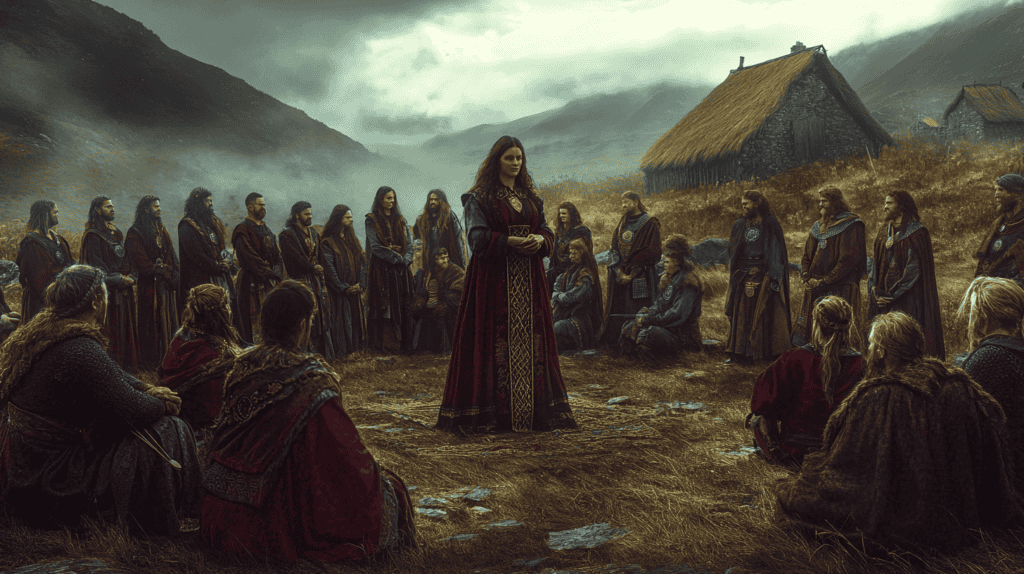

Gender Roles and Succession

One of the most intriguing aspects of Pictish society was its approach to gender roles and succession. Unlike many contemporary cultures, Pictish women were regarded as equals to men. This equality extended to matters of leadership and succession.

Pictish succession was matrilineal, meaning that leadership passed through the mother’s side of the family. A reigning chief would typically be succeeded by his brother or nephew, rather than his son. This system stands in stark contrast to the patrilineal succession common in many other cultures of the time.

Religion and Beliefs

Before the arrival of Christianity, the Picts practiced a form of tribal paganism. Their beliefs appear to have centered around goddess worship and a deep reverence for nature. Certain sites across their territory were considered to have supernatural power, believed to be places where the goddess lived, walked, or performed miracles.

Interestingly, the concept of “sin” seems to have been absent from Pictish belief systems, a characteristic shared with many other pagan religions. The Pictish goddess was thought to live among the people, fostering a close relationship between the divine and the mortal realms.

Art and Craftsmanship

Despite leaving no written records, the Picts were far from an uncultured people. The Picts are perhaps best known for their symbol stones, intricately carved standing stones that can still be found throughout Scotland. These stones feature a variety of symbols, including animals, objects, and abstract designs. While the exact meanings of these symbols remain a subject of debate among scholars, they likely served important cultural, religious, or political functions.

The Battle of Mons Graupius

The Picts’ interactions with the Roman Empire form a significant chapter in their history. When the Romans began their conquest of Britain in 43 CE, the Picts living in a remote and harsh landscape stood as a formidable obstacle to their northward expansion.

In 83 CE, the Roman governor of Britain, Julius Agricola, led an invasion into northern Scotland. This campaign culminated in the Battle of Mons Graupius, where the Picts, led by a chieftain named Calgacus, faced the Roman legions.

Tacitus, the Roman historian, provides the only account of this battle. He attributes a rousing speech to Calgacus, though many historians believe this to be Tacitus’ own creation. In this speech, Calgacus is said to have declared:

“To all of us slavery is a thing unknown; there are no lands beyond us, and even the sea is not safe, menaced as we are by a Roman fleet. And thus in war and battle, in which the brave find glory, even the coward will find safety”.

While the Romans claimed victory at Mons Graupius, they failed to capitalize on this success. The decentralized nature of Pictish society, with no major cities to conquer, presented a unique challenge to the Roman model of conquest.

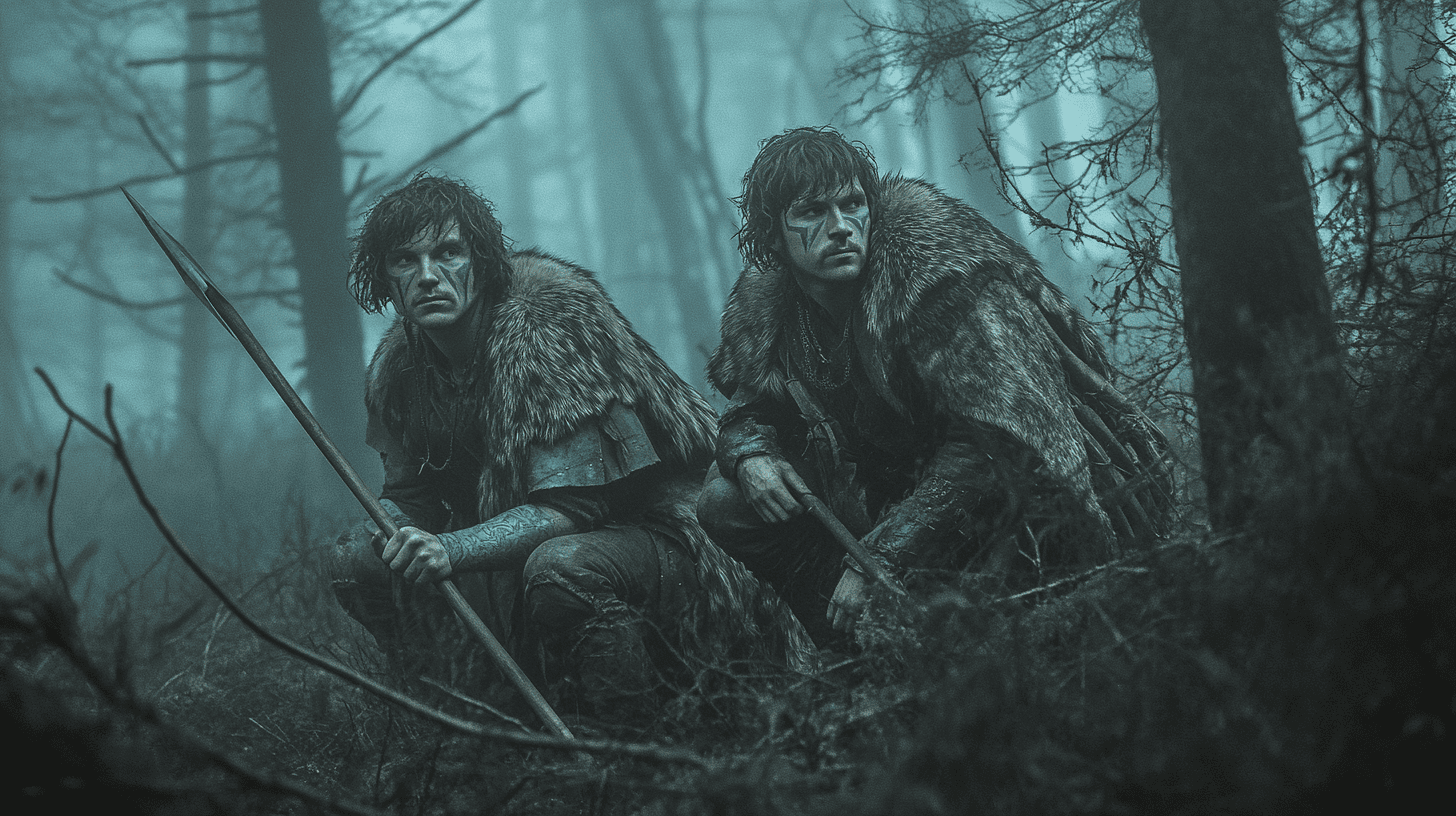

Guerrilla Warfare and Roman Withdrawal

Despite their victory at Mons Graupius, the unique societal structure of the Picts presented an unprecedented challenge to Roman conquest strategies.

The Pictish territories lacked the centralized urban centers that typically served as focal points for Roman subjugation. This decentralized nature of Pictish society confounded the established Roman methodology of conquest and control, which had proven effective across much of Europe.

The Picts’ nomadic lifestyle and intimate knowledge of their terrain allowed them to evade Roman attempts at domination. Their ability to rapidly relocate and sustain themselves off the land meant that there were no fixed settlements to capture or agricultural centers to destroy.

Following Mons Graupius, the Picts adopted guerrilla tactics, refusing to engage the Romans in open battle. Instead, the Picts relied on quick raids and their ability to disappear into the challenging Scottish terrain. This approach, unfamiliar to the Roman legions, rendered their traditional military strategies ineffective. The Romans found themselves unable to adapt to this new paradigm of warfare, leaving them incapable of subduing an enemy whose way of life and combat style were unlike anything they had previously encountered.

This guerrilla warfare strategy, ultimately prevented the Romans from conquering what would become Scotland, despite repeated attempts. The construction of Hadrian’s Wall in 122 CE and the Antonine Wall in 142 CE served as physical and psychological barriers between Roman Britain and the Pictish lands to the north.

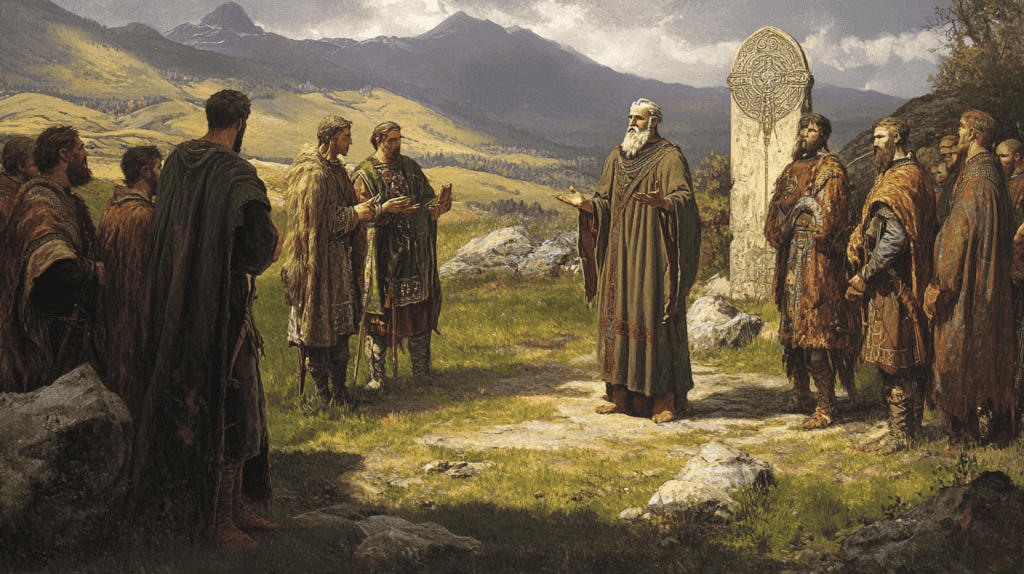

The Coming of Christianity

The arrival of Christianity in Pictish territories marked a significant turning point in their history. Christian missionaries began making inroads among the Picts from around 397 CE, starting with St. Ninian.

The introduction of Christianity had profound effects on Pictish society and culture. As historian Stuart McHardy notes, “Where the Roman Empire failed to conquer the Picts, the Christian Church succeeded”. The gradual adoption of Christianity led to changes in Pictish beliefs, art, and potentially their social structure.

Later History and Legacy

The Picts continue to be mentioned in historical records until around 900 CE. After this point, they seem to disappear from written history. However, this doesn’t mean they vanished or were annihilated. Instead, it’s more likely that they merged with the southern Scots culture, blending into a unified Scottish identity.

The legacy of the Picts lives on in Scotland’s rich cultural heritage. Their symbol stones continue to intrigue archaeologists and historians, while their successful resistance against Roman invasion remains a point of pride in Scottish history.