The year 754 CE marked a crucial moment in Dark Ages European history, as it witnessed the formation of a crucial alliance between the Papacy and the Frankish monarchy, leading to the establishment of the Papal States. This event, known as the Donation of Pepin, reshaped the political landscape of medieval Europe and had far-reaching consequences for centuries to come.

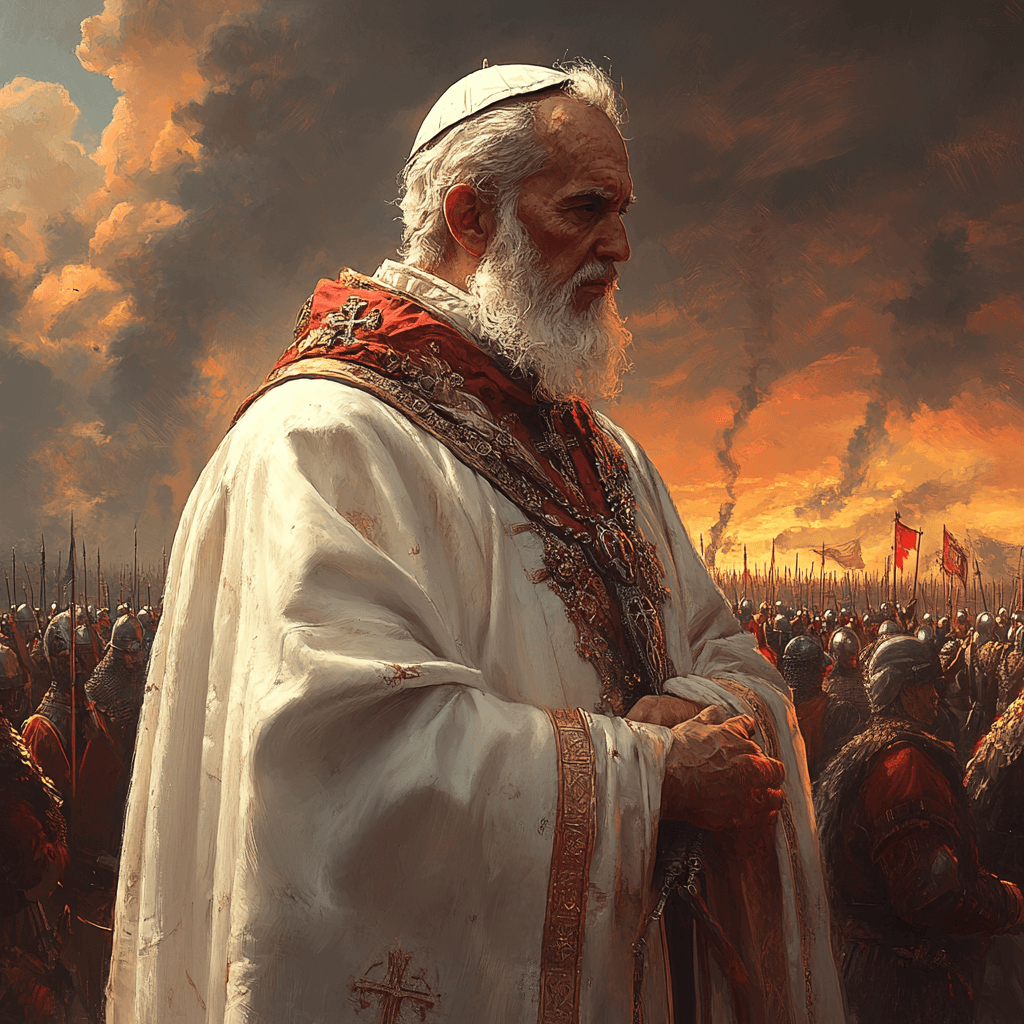

The Papal Predicament

In the mid-8th century, the papacy found itself in a precarious position. The Byzantine Empire, which had long been the protector of the Church, was losing its grip on Italy. The Lombards, led by their aggressive king Aistulf, had seized control of the Exarchate of Ravenna in 751, leaving the papacy vulnerable and isolated. Pope Stephen II, who ascended to the papal throne in 752, realized that he needed a new powerful ally to safeguard the Church’s interests.

Stephen II turned his attention northward to the rising power of the Franks. In 750, Pepin the Short had deposed the last Merovingian king with the approval of Pope Zacharias, Stephen’s predecessor. This created an opportunity for a mutually beneficial alliance between the papacy and the new Frankish dynasty.

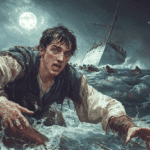

The Historic Meeting

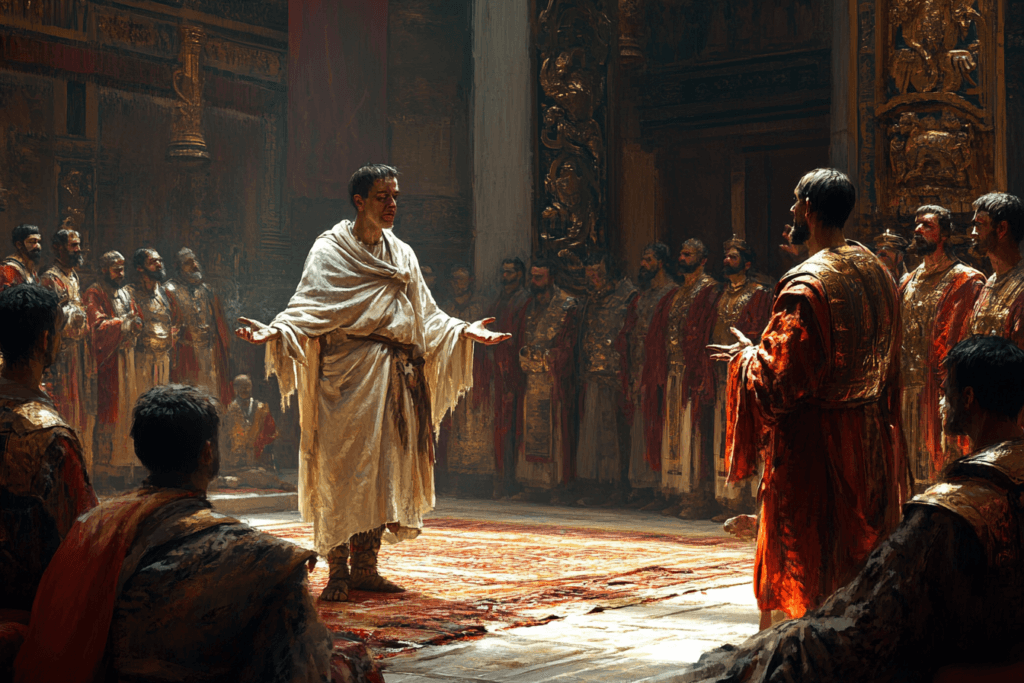

In January 754, Pope Stephen II made a perilous journey across the Alps, becoming the first pope to do so. He was met at the Alps by Pepin’s young son, Charles (later known as Charlemagne). The pope then traveled to the Frankish royal palace at Ponthion, where he was welcomed by Pepin the Short.

The meeting between Pope Stephen II and Pepin was a masterclass in diplomacy. The pope, dressed in sackcloth and ashes, humbly approached Pepin, asking for his support in defending “the suit of St Peter and of the republic of the Romans”. Pepin, recognizing the political and spiritual advantages of aligning with the papacy, responded favorably.

The Promise of Quierzy

In April 754, Pepin convened a general assembly at Quierzy-sur-Oise. Despite some opposition from his nobles, Pepin publicly restated his promise to the Pope and enumerated the territories he would restore. This verbal commitment was then put into writing, although the exact contents of this document remain a subject of debate among historians.

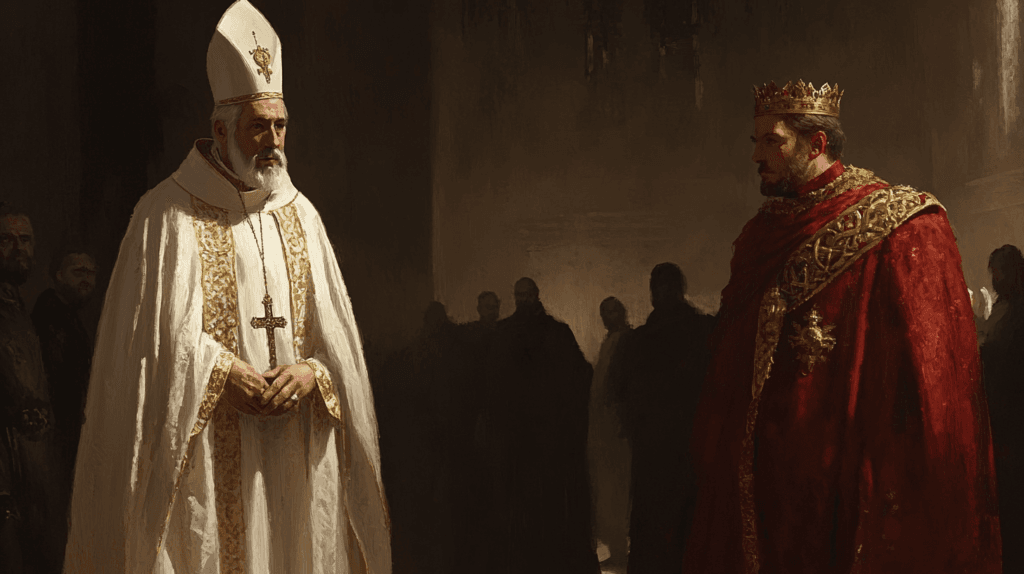

The Anointing of Kings

The alliance between the papacy and the Franks was solemnized on July 28, 754, in a grand ceremony at the Basilica of Saint-Denis. Pope Stephen II anointed Pepin and his sons, Charles (Charlemagne) and Carloman, as kings of the Franks and patricians of the Romans. This act had profound implications:

- It legitimized Pepin’s rule and the Carolingian dynasty.

- It established a precedent for papal involvement in the coronation of European monarchs.

- It created a strong bond between the Frankish kingdom and the papacy.

The Lombard Threat and Pepin’s Campaigns

The newly forged alliance was soon put to the test. King Aistulf of the Lombards continued his aggressive expansion, threatening Rome itself. In response to papal pleas, Pepin led two military campaigns into Italy.

In 754, Pepin answered Stephen’s plea for aid. Leading his army across the Alps, he confronted Aistulf near Pavia. The Lombards, unprepared for the scale and organization of Pepin’s forces, capitulated. A treaty was brokered: Aistulf agreed to restore papal lands and cease his aggression. Pepin returned triumphantly, but the peace was short-lived.

By 756, Aistulf had reneged on his promises, prompting Pepin’s second campaign. This time, the Franks besieged Pavia with greater determination. Aistulf, facing an overwhelming force, surrendered once more. Pepin demanded the lands of the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Pentapolis, not for himself but for the pope. This act, later called the Donation of Pepin, laid the foundation for the Papal States and cemented the pope’s temporal power.

The Donation of Pepin

Following his victories, Pepin made a momentous decision that would reshape the political map of Italy. He “restored” to the papacy the lands formerly constituting the Exarchate of Ravenna and other territories in central Italy. This act, known as the Donation of Pepin, laid the foundation for the Papal States.

The exact extent of the territories granted to the papacy is not entirely clear, but they likely included:

- The Exarchate of Ravenna

- The Duchy of Rome

- Parts of the Pentapolis

It’s important to note that many of these lands had previously been under Byzantine control. Pepin’s “donation” was, in effect, granting territories to which he had no legal claim!

The Confession of St. Peter

The formal act of donation took place in 756, following Pepin’s second campaign against the Lombards. In a symbolic gesture, the keys to the cities and territories that had submitted to papal authority were collected. These keys, along with a list of the cities involved (known as the Confession of St. Peter), were placed on the altar of Old St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome1.

While not directly related to the events of 754, it’s worth mentioning the Donation of Constantine, a forged document that played a significant role in this period. This document, likely created between 751-756, purported to be a 4th-century grant from Emperor Constantine I, giving the papacy authority over vast territories.

Although now known to be a forgery, the Donation of Constantine was likely used to bolster the papacy’s claims and to persuade Pepin to make his own donation. The document’s influence extended well beyond this period, shaping papal claims to temporal power for centuries.

Consequences and Legacy

The Donation of Pepin had far-reaching consequences.

Creation of the Papal States. It provided a legal basis for the papacy’s temporal rule over a significant portion of central Italy, establishing the Papal States that would last until Italian unification in the 19th century.

Shift in European Power Dynamics. The alliance between the Franks and the papacy altered the balance of power in Europe, weakening Byzantine influence in Italy and setting the stage for the rise of the Carolingian Empire. The alliance formed in 754 paved the way for the later coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in 800, further cementing the relationship between the Frankish/German monarchs and the papacy. The papacy’s alignment with the Franks and its acquisition of temporal power contributed to the growing rift with the Byzantine Empire, eventually leading to the East-West Schism.