Saint Columba, also known as Colm Cille (“Dove of the Church”), was a towering figure in early dark ages Christianity, renowned for his missionary zeal, scholarship, and influence on monasticism in the British Isles. Born around 521 CE in Gartan, modern-day County Donegal, Ireland, Columba hailed from a royal lineage. His family belonged to the powerful Úneíl clan, which traced its ancestry to Niall of the Nine Hostages, a legendary Irish king. This noble heritage afforded him both privilege and a profound sense of duty, shaping his path as a spiritual leader and missionary.

Early Life and Education

Columba’s early life was steeped in the cultural and spiritual traditions of Ireland, which was undergoing a transformative period of Christianization. He demonstrated a keen intellect and spiritual inclination from a young age. Educated at monastic schools, including Clonard under the tutelage of Saint Finnian, Columba was part of a generation of influential Irish monks who would become known as the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland.” His studies encompassed Latin, scripture, and the traditions of the Celtic Church, which blended Christian teachings with indigenous Irish customs.

Ordained as a deacon and later as a priest, Columba displayed exceptional skill as a scribe and scholar. He was instrumental in transcribing religious texts, contributing to the preservation and dissemination of Christian knowledge. One famous story recounts a dispute between Columba and Saint Finnian over a copy of a Psalter that Columba had secretly transcribed. The matter escalated to a legal conflict, with the High King of Ireland ruling in Finnian’s favor, declaring, “To every cow belongs its calf, and to every book its copy.”

The Battle of Cúl Dreimhne and Exile

Columba, however, rejected the king’s judgment, perceiving it as an affront to his rights. The clash over the psalter soon transformed into a far more deadly contest of power. Columba, with a fierce determination that would become his trademark, reportedly incited a rebellion among the Uí Néill clan, challenging the king’s authority. The ensuing battle was catastrophic, with up to 3,000 casualties, a devastating toll that would haunt Columba’s conscience for years to come. Indeed, whether it was a punishment or his own guilt that drive him, Columba set out to convert as many people to Christianity as had been lost at the very bloody Battle of Cul Dreimhne.

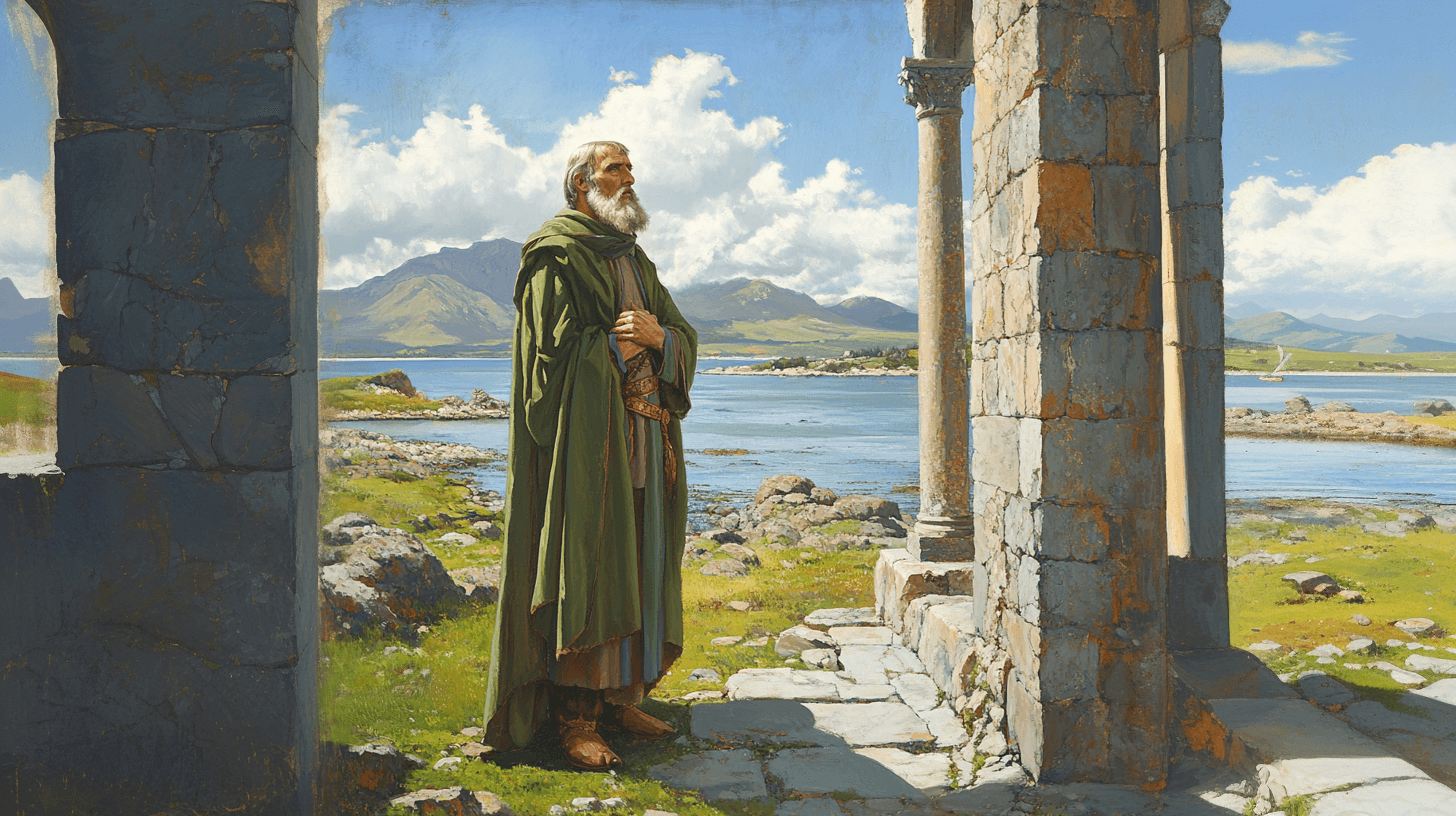

In 563 CE, Columba and a small band of followers set sail for Scotland, seeking to establish a new mission among the Picts, a tribal people who inhabited much of northern Scotland. Their journey brought them to the island of Iona, a small, windswept isle off the western coast of Scotland. There, Columba founded a monastery that would become one of the most significant centers of Christian learning and missionary activity in the British Isles.

The Iona Monastery

The monastery at Iona was more than a religious community; it was a beacon of scholarship, culture, and spirituality. Columba and his monks devoted themselves to prayer, study, and manual labor, embodying the ascetic ideals of early Irish monasticism. The monastery’s scriptorium became renowned for its production of illuminated manuscripts, including works that likely influenced the creation of the Book of Kells, one of the most celebrated artifacts of medieval art.

Columba’s leadership and charisma were instrumental in Iona’s success. He combined a fervent spirituality with a pragmatic approach to governance, forging alliances with local leaders and engaging in diplomatic efforts. His efforts among the Picts included converting their king, Bridei mac Maelchon, to Christianity, a milestone that solidified the faith’s foothold in Scotland.

Miracles and Legends

Columba’s life is steeped in legends, many of which were recorded in the Vita Columbae (“Life of Columba”), written by his successor, Adomnán, a century after his death. These stories portray Columba as a miracle worker and a figure of immense spiritual power. He is said to have performed healings, calmed storms, and even confronted a monster in Loch Ness, a tale often cited as one of the earliest references to the Loch Ness Monster.

Despite the fantastical elements, these legends reflect the profound reverence in which Columba was held by his contemporaries and later generations. They also underscore his role as a spiritual mediator, bridging the earthly and divine realms.

Legacy and Influence

Columba’s influence extended far beyond his lifetime. The Iona monastery became a hub for missionary activity, sending monks to establish communities throughout Scotland and northern England. These efforts played a pivotal role in the Christianization of the region and the preservation of classical knowledge during the so-called “Dark Ages.“

Columba’s model of monasticism, characterized by rigorous discipline, scholarship, and missionary zeal, left an indelible mark on the Celtic Church. His spiritual writings and teachings, though sparse in surviving records, reveal a profound commitment to the contemplative life and a deep love for nature, reflecting the intertwined spiritual and natural worlds in Celtic Christianity.

Death and Veneration

Columba died on June 9, 597 CE, reportedly after spending the night in prayer. His death marked the end of a remarkable life, but his legacy endured. He was buried on Iona, which became a revered pilgrimage site and the burial place of kings from Scotland, Ireland, and Norway.

Over the centuries, Columba was venerated as a saint, with his feast day celebrated on June 9. Churches, schools, and institutions across the world bear his name, testifying to his enduring influence.