The dawn of July 4, 1187, broke over the parched hills of Galilee, casting long shadows over an army doomed to destruction. It was on this day that the Crusader forces, largely composed of French knights and their allies, suffered a catastrophic defeat at the hands of Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub – known to the West simply as Saladin. By sunset, the Crusader army had ceased to exist, their proud warriors either dead, captured, or scattered to the winds. The Battle of Hattin was not just a military debacle; it was the beginning of the end for Christian control of the Holy Land.

The Road to Disaster

In the late 12th century, the Kingdom of Jerusalem was a fragile entity, constantly under threat from its Muslim neighbors. Established in the wake of the First Crusade, the kingdom had managed to maintain its presence in the Holy Land for nearly a century. However, internal divisions and the rising power of Saladin’s Ayyubid dynasty posed significant challenges to its continued existence.

Saladin, born Yusuf ibn Ayyub, had risen to power as the Sultan of Egypt and Syria. A skilled military commander and astute politician, Saladin had united much of the Muslim world under his banner, with the ultimate goal of reclaiming Jerusalem from the Crusaders. His strategic acumen and charismatic leadership would prove crucial in the events leading up to and during the Battle of Hattin.

In the years preceding the battle, tensions between the Crusaders and Saladin’s forces had been steadily increasing. Raynald of Châtillon, a notorious Crusader lord, had been conducting raids on Muslim caravans in violation of a truce and even threatened to attack the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. These provocations, combined with Saladin’s growing power, made conflict inevitable.

The Conflict Begins

As July 1187 approached, Saladin devised a cunning plan to lure the Crusader army out of their fortified positions. On July 2, he launched an attack on the city of Tiberias, which belonged to Raymond III of Tripoli, one of the leading nobles in the Crusader army. The assault quickly overwhelmed the city’s defenses, forcing the French defenders to retreat to the citadel.

News of the attack on Tiberias reached the Crusader camp at Sepphoris, sparking a heated debate among the Christian leaders. Some, including Raymond III himself, argued against marching out to relieve Tiberias, recognizing the danger of leaving their secure position. Others, however, pushed for immediate action.

In the end, the more aggressive faction prevailed, and on July 3, King Guy of Lusignan, the ruler of Jerusalem, led his entire army out of their fortified positions to relieve the siege of Tiberius. However, they soon found themselves ensnared in Saladin’s masterful trap. Under the blazing summer sun, without access to water, and harassed by relentless enemy skirmishers, the Crusaders marched toward their doom.

The Furnace of Hattin

By the afternoon of July 3, the Crusaders were near collapse. Their water supplies had run dry, their ranks thinned by incessant arrow fire. As night fell, they made camp on the arid plain near the Horns of Hattin, two rocky outcrops of an extinct volcano. overlooking the battlefield. This defensive position, while offering some protection, also sealed their fate by cutting them off from any hope of retreat or resupply.

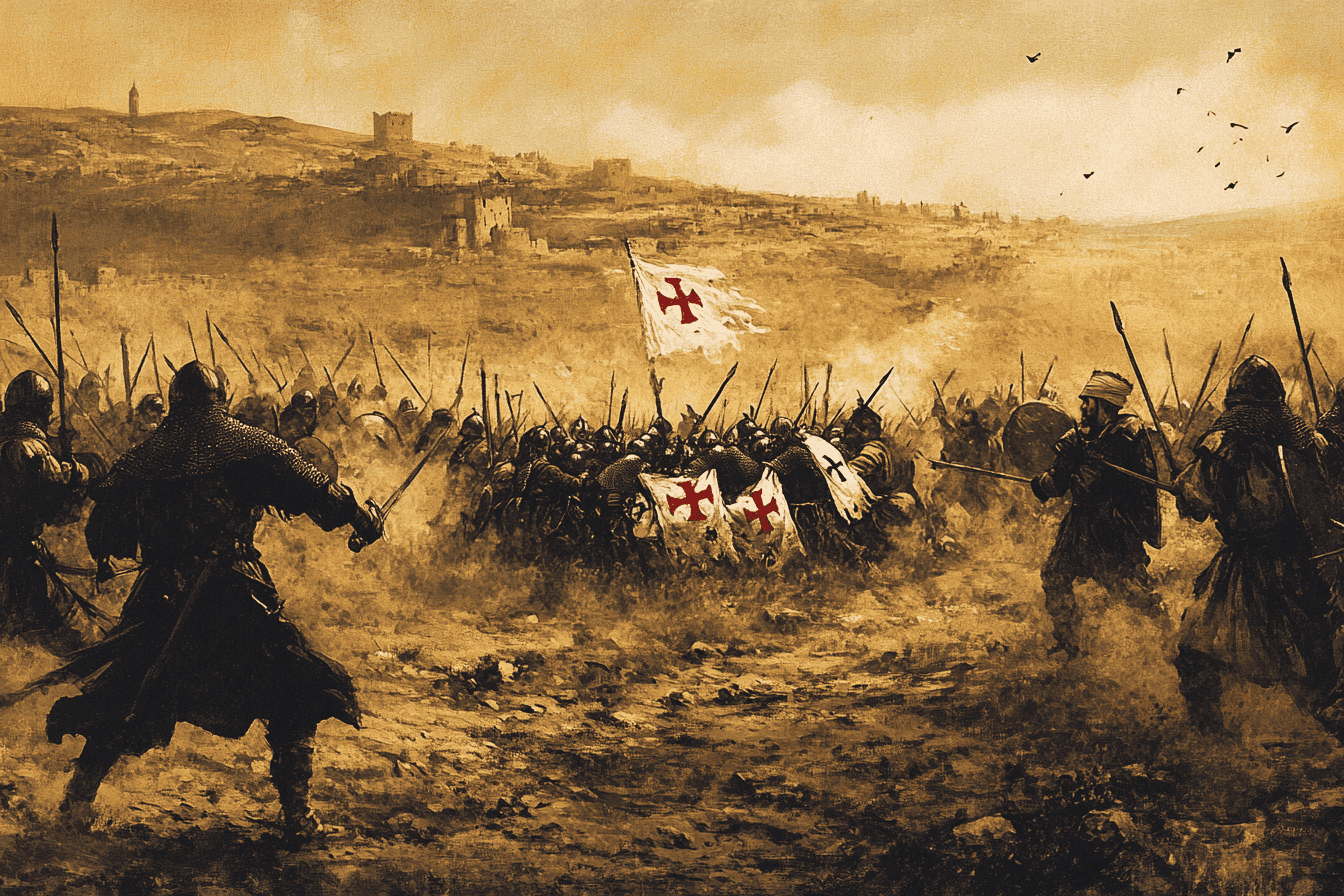

Recognizing the Crusaders’ vulnerable position, Saladin moved to encircle the enemy forces. His army, numbering around 30,000 men, outnumbered the Crusaders’ 20,000. More importantly, Saladin’s troops were well-supplied and in high spirits, in stark contrast to their dehydrated and dispirited opponents

Saladin tightened the screw. Setting the dry grass ablaze, his forces engulfed the Crusader camp in smoke, choking and disorienting the knights. By morning, when the final assault came, the Crusaders were little more than helpless prey.

Saladin’s forces, disciplined and well-hydrated, closed in from all sides. The Frankish knights, exhausted and desperate, attempted to break out. One contingent of Christian knights managed to punch through and escape to Tyre, but these were the exception. Most of the French cavalry’s charges proved ineffective against the disciplined Muslim forces.

As the morning wore on, the Crusader army began to disintegrate. Many of the infantry fled to the Horns of Hattin, effectively abandoning the fight. The knights and mounted sergeants, though disorganized, continued to resist, but their efforts were ultimately futile.

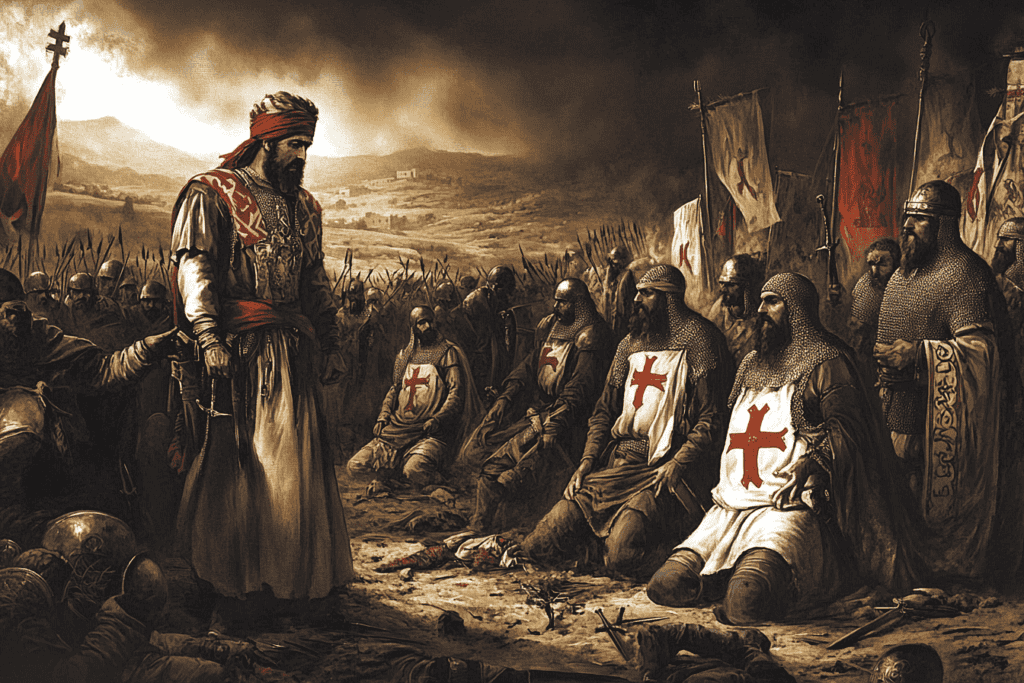

Overwhelmed by thirst, exhaustion, and the relentless attacks of Saladin’s forces, the Crusader army collapsed. By midday, the battle was over. King Guy and the surviving nobles surrendered, while thousands of foot soldiers were slaughtered or enslaved. In the final stages of the battle, Saladin’s forces captured most of the Crusader nobility, including King Guy of Lusignan and Raynald of Châtillon.

The Aftermath

The scene in Saladin’s tent following the battle has become legendary. Saladin offered water to the captive King Guy, a gesture signifying that his life would be spared. When Guy passed the water to Raynald, however, Saladin knocked the goblet away, declaring that he had not offered hospitality to “this evil man”.

Saladin then charged Raynald with breaking the truce between the Crusaders and the Muslims. In a dramatic moment, Saladin himself executed Raynald, either striking him down with his own sword or ordering his guards to behead him. This act of personal vengeance against the man who had so provoked the Muslims sent a clear message about the consequences of violating agreements with Saladin.

The majority of the Crusader forces were either killed in battle or captured. The military orders, such as the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller, suffered particularly heavy losses. Saladin ordered the execution of many of the captured Templars and Hospitallers, viewing them as the most dedicated and dangerous of his enemies.

Among the most significant losses for the Crusaders was the capture of the relic of the True Cross, a piece of wood believed to be from the cross on which Jesus was crucified. The loss of this holy relic was a devastating blow to Crusader morale and symbolized the magnitude of their defeat.

The Fall of Jerusalem

The Battle of Hattin effectively destroyed the military capability of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. In the months following the battle, Saladin’s forces swept through the Holy Land, capturing city after city. On October 2, 1187, Jerusalem itself fell to Saladin, ending nearly nine decades of Christian rule over the holy city.

Beyond Jerusalem, the Battle of Hattin led to the near-total collapse of the Crusader states. Within months, Saladin had captured most of the important cities and fortresses held by the Franks. Only a few coastal strongholds, such as Tyre, managed to hold out against the Muslim advance.

News of the disaster at Hattin and the subsequent fall of Jerusalem sent shockwaves through Europe. Pope Gregory VIII issued a call for a new crusade to reclaim the Holy Land. This appeal would eventually result in the Third Crusade, led by figures such as Richard the Lionheart of England, Philip II of France, and Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire.

For the Crusaders, the battle was more than a defeat – it was an annihilation. The once-mighty French-led forces of the Kingdom of Jerusalem had, in a single day, been erased from the map. The loss at Hattin was a grim reminder that in war, arrogance and poor strategy can lead even the strongest armies to utter ruin.