The Albigensian Crusade, a dark chapter in medieval European history, was a brutal campaign that lasted from 1209 to 1229. This crusade, unlike those aimed at the Holy Land, targeted fellow Christians within Western Europe, specifically the Cathars in the Languedoc region of southern France.

Origins and Causes

The roots of this conflict lay in the rise of Catharism, a Christian movement that the Roman Catholic Church branded as heretical. The Cathars, also known as Albigensians due to their concentration around the town of Albi, adhered to a neo-Manichaean dualism. They believed in two principles: one good and one evil, with the material world being inherently evil.

This belief system posed a significant threat to the established Catholic Church. The Cathars rejected many core Catholic doctrines, including baptism and the church hierarchy. Their popularity in southern France, particularly among the nobility, alarmed Pope Innocent III, who saw their spread as a danger to the unity and authority of the Church.

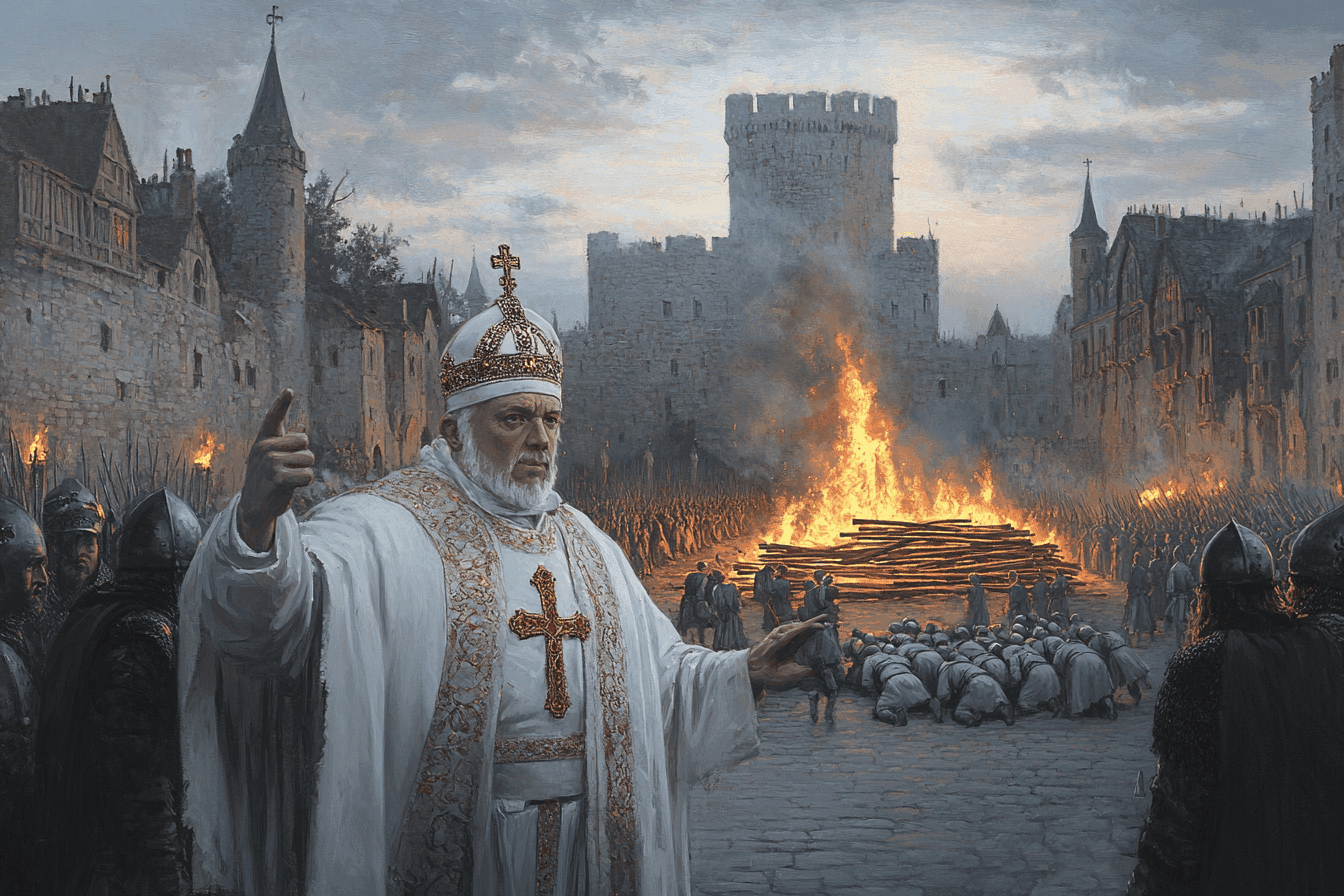

The Call to Arms

In 1209, Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the Cathars. This unprecedented move marked the first time a pope had sanctioned a crusade against other Christians. The pope’s call was met with enthusiasm, particularly in northern France. For many pious warriors, it offered an opportunity to gain a crusade indulgence – a remission from punishment in the afterlife for sin – without the need to travel to distant lands.

The Crusade Begins

The army arrived at the gates of Béziers on July 21, 1209. The city, a known Cathar stronghold, was under the control of Raymond Roger Trencavel, the young Viscount of Béziers and Carcassonne. Despite being warned of the approaching army, most of Béziers’ residents, including many Catholics, had chosen to remain within the city walls.

Arnaud Amalric, hoping to avoid a protracted siege, sent the Bishop of Béziers, Renaud de Montpeyroux, to negotiate with the townspeople. The crusaders demanded the surrender of 222 suspected heretics, a list that included both Cathars and Waldensians. However, the citizens of Béziers, in a show of solidarity, refused to hand over their neighbors.

On the morning of July 22, events took an unexpected and tragic turn. A group of young men from Béziers, in a rash act of defiance, launched a sortie against the crusaders. This ill-fated attack was quickly repelled, and in the chaos of the retreat, the city gates were left open. Seizing the opportunity, the crusaders’ servant boys and camp followers surged into the city, followed closely by the knights and soldiers.

What followed was a scene of unimaginable carnage. The crusaders, caught up in a frenzy of violence, began indiscriminately slaughtering the city’s inhabitants. Men, women, and children were cut down in the streets. Many sought refuge in the city’s churches, including the Cathedral of Saint Nazaire, but even these sanctuaries offered no protection.

It was in this context that the papal legate Arnaud Amalric allegedly uttered the infamous words that would come to epitomize the brutality of the crusade: “Kill them all. God will know his own.” While the authenticity of this quote is debated, it captures the merciless spirit that drove the crusaders. This chilling command resulted in the slaughter of an estimated 20,000 men, women, and children of the Cathar and Catholic Christian faiths. The massacre was swift and thorough. Within hours, thousands lay dead. The city was then set ablaze, with many of those who had survived the initial onslaught perishing in the flames.

The fall of Béziers sent shockwaves through the Languedoc. The speed and savagery of the attack struck terror into the hearts of other towns and cities in the region. Many, including the important center of Narbonne, chose to surrender without a fight rather than face a similar fate.

The capture of Béziers was a pivotal moment in the Albigensian Crusade. It demonstrated the crusaders’ willingness to use extreme violence, not just against the Cathars, but against entire populations. The massacre also revealed how quickly the crusade’s original religious objectives could be overshadowed by bloodlust and the desire for plunder.

The Fall of Carcassonne

Following the massacre at Béziers, the crusaders turned their attention to Carcassonne, a major Cathar stronghold. The siege began on August 1, 1209. Despite Carcassonne’s formidable defenses, including double walls, the crusaders employed a ruthless strategy. They cut off the city’s water supply at the height of summer, forcing the defenders into a desperate situation.

For several weeks, the people of Carcassonne, led by Viscount Raymond-Roger Trencavel, held out against the besiegers. However, as food and water became scarce, Trencavel attempted to negotiate. In a treacherous move, he was taken captive during the talks. With their leader imprisoned and facing starvation, the defenders were forced to surrender on August 15.

Simon de Montfort’s Rise

The fall of Carcassonne marked a turning point in the crusade. Simon de Montfort, a northern French nobleman who had previously participated in the Fourth Crusade, emerged as the dominant military leader. He gained personal control over much of the conquered territory, setting the stage for a shift in the region’s power dynamics.

The Crusade Intensifies

As the crusade progressed, it increasingly took on the character of a territorial conquest rather than a purely religious mission. The traditional Occitan nobility, many of whom had supported the Cathars or opposed the crusade, were dispossessed of their lands and titles. In their place, northern French nobles and the Catholic Church assumed control, altering the region’s political landscape and integrating it more closely into the French crown.

The crusaders continued their campaign of terror, capturing towns such as Castelnaudary, Lastours, and Minerve in 1211. In these conquered territories, they conducted mass burnings of Cathars who refused to recant their faith.

The Battle of Muret

The Battle of Muret, fought on September 12, 1213, was a decisive and dramatic confrontation during the Albigensian Crusade. It pitted the forces of Simon de Montfort, leader of the crusaders, against a coalition led by King Peter II of Aragon and Raymond VI of Toulouse.

The crusade’s brutality and territorial ambitions alarmed local rulers. Raymond VI of Toulouse, who had been exiled by Montfort, sought assistance from his brother-in-law, King Peter II of Aragon. Peter, a devout Catholic and experienced military leader, decided to intervene. He crossed the Pyrenees with an army in August 1213, joining forces with Raymond VI and other Occitan lords. Together, they formed a formidable coalition estimated at 30,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.

Their target was Muret, a small but strategically important town near Toulouse that was held by Montfort’s forces. By early September, Peter’s coalition had laid siege to Muret with siege engines and encampments surrounding the town. Inside the fortress were only about 900 crusader knights and 1,200 infantry—vastly outnumbered but determined to hold their ground.

Simon de Montfort knew that he could not withstand a prolonged siege. Supplies were limited, and his forces were too small to defend against such overwhelming numbers indefinitely. Instead of waiting for defeat, he devised a bold plan: a surprise cavalry attack on the besieging army.

A Daring Strike

On the morning of September 12, Montfort led his knights out of Muret under cover of darkness. Dividing his cavalry into three squadrons for tactical flexibility, he crossed the Louge River and launched a sudden assault on the coalition forces. The first two squadrons, commanded by William of Barres, struck directly at the Aragonese front lines under Count Raymond Roger of Foix.

The coalition forces were caught off guard. The Aragonese cavalry struggled to maintain cohesion as Montfort’s heavy knights crashed into their ranks with devastating force. King Peter II himself was in the second line of his army but had disguised himself in another soldier’s armor to avoid being targeted directly. However, this tactic backfired when confusion spread among his troops about his whereabouts.

Montfort’s third squadron executed a flanking maneuver that struck Peter’s right flank. In the chaos that followed, King Peter was killed—either during this initial clash or shortly afterward when crusaders deliberately sought him out after identifying his standard. According to some accounts, Peter shouted “Here is your king!” in an attempt to rally his men but was ignored or unheard amidst the tumult.

The death of Peter II proved catastrophic for the coalition forces. With their leader gone and morale shattered, they began to retreat in disarray. Montfort’s knights pursued them relentlessly across the battlefield, cutting down fleeing soldiers as they went.

Meanwhile, Montfort regrouped part of his force and turned it against the Toulousain militia that was still besieging Muret. Learning of Peter’s death and seeing Montfort’s cavalry returning victorious, these troops panicked and fled toward the Garonne River. Many were slaughtered during their retreat.

Aftermath and Consequences

Crusader losses were minimal – reportedly around 100 men – while the coalition suffered approximately 7,000 dead. The defeat effectively ended Aragonese influence in Languedoc and dealt a severe blow to Raymond VI’s efforts to reclaim his lands.

Politically, Peter II’s death had far-reaching consequences. His young son James I inherited the throne of Aragon but was left vulnerable as a hostage under Montfort’s control until later released by papal intervention. With Aragon no longer able to challenge him in Languedoc, Montfort consolidated his hold over much of southern France.

For Toulouse and its allies, Muret marked a turning point in their resistance against the crusaders. Although sporadic fighting continued for years afterward, this battle solidified French dominance over Occitania and paved the way for its eventual integration into the French crown.

The Siege of Toulouse

The Fourth Lateran Council, convened by Pope Innocent III, affirmed de Montfort as the Count of Toulouse and rescinded the crusade indulgence for the war so that a new crusade to the East could be organized. By 1217, Simon de Montfort, the ruthless and capable leader of the crusader forces, had seemingly consolidated his control over much of the Languedoc region. However, Raymond and his son, Raymond VII, were far from defeated and had begun plotting to reclaim their lost territories.

On September 13, 1217, in a bold and unexpected move, Raymond VI managed to slip into Toulouse under the cover of early morning mist. The response from the city’s inhabitants was nothing short of ecstatic. As word spread of their beloved count’s return, the people of Toulouse erupted in jubilation. They mobbed Raymond, kissing his clothes, feet, legs, arms, and even his fingers in a display of fervent loyalty and relief. In the ensuing chaos, French crusaders found themselves under attack, with many being killed by the enraged populace.

The sudden and violent expulsion of Montfort’s forces from Toulouse caught the crusaders completely off guard. Simon de Montfort, who was elsewhere at the time, raced back to the city upon hearing the news.

The citizens of Toulouse, galvanized by Raymond’s return and their successful uprising, had swiftly organized themselves for defense. They repaired and reinforced the city walls, determined to resist any attempt by Montfort to retake the city. Their resolve was strengthened by the knowledge that surrender would likely result in brutal reprisals, given Montfort’s reputation for ruthlessness.

Montfort, realizing the gravity of the situation, immediately began preparations for a siege. However, his forces were too few to completely encircle the city, allowing supplies and reinforcements to continue reaching the defenders. This strategic disadvantage would prove crucial in the months to come.

The Tide Turns

As spring arrived in 1218, the tide began to turn against the crusaders. The defenders of Toulouse, inspired by a suggestion from a certain “maestre” Bertran, constructed a formidable trebuchet. This powerful siege engine would play a decisive role in the coming events.

On June 3, 1218, the crusaders attempted to approach the walls with a “cat,” a leather-covered, steeply-gabled mobile shelter. However, the defenders’ trebuchet quickly dispatched this threat, demonstrating the effectiveness of their new weapon. Emboldened by this success, the people of Toulouse launched a sortie on June 25 to burn the crusaders’ siege equipment.

It was during this counterattack that fate struck a decisive blow against the crusaders. As Simon de Montfort rushed to aid his brother Guy, who had been wounded by a crossbow, he was hit on the head by a large stone launched from one of the defenders’ siege engines. Some accounts attribute this fatal shot to the women and girls of Toulouse operating the trebuchet or a mangonel.

The death of Simon de Montfort on June 25, 1218, was a catastrophic blow to the crusader cause. The crusaders, demoralized by the loss of their leader and facing increasingly effective resistance from the defenders, were unable to maintain their position. By July 25, 1218, just one month after Simon’s death, the siege was lifted.

The capture of Toulouse in 1218 represented a significant victory for the Cathar cause and the people of Languedoc. It demonstrated that resistance against the northern invaders was not only possible but could be successful. The event reinvigorated the defenders of southern France and challenged the notion that the Albigensian Crusade was nearing its conclusion.

The Treaty of Paris

After Simon de Montfort’s death on June 25, 1218 his son Amaury inherited command but lacked his father’s military prowess. Raymond VI and his son Raymond VII capitalized on this momentum, recapturing lost territories. The crusade dragged on for several more years, with the French crown under Louis VIII eventually intervening in 1226.

The conflict officially ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1229, when Raymond VII submitted to the French king. While the crusade failed to completely eradicate Catharism, it significantly reduced its influence and led to Languedoc’s integration into the French kingdom

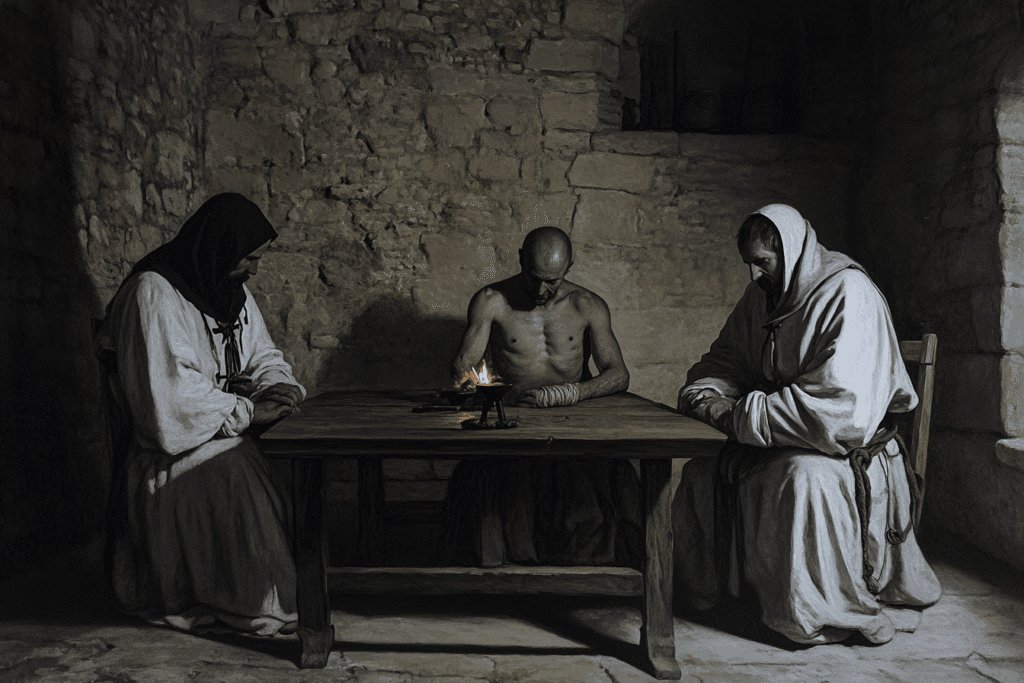

The Inquisition

The Inquisition, established in the early 13th century, played a crucial role in the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade. Tasked with identifying, interrogating, and punishing heretics, the Inquisition operated with particular ruthlessness in the Languedoc region.

Inquisitors, often Dominican or Franciscan friars, conducted rigorous and severe interrogations. Suspected heretics faced tribunals without the right to legal representation or the ability to confront their accusers. The use of torture to extract confessions was not uncommon.

Those found guilty of heresy could face a range of penalties, from penance and imprisonment to execution, typically by burning at the stake. The activities of the Inquisition created an atmosphere of fear and suspicion, as neighbors and family members could be compelled to testify against each other.

The Fall of Montségur

The Fall of Montségur in 1244 marked the dramatic conclusion of the Albigensian Crusade and the effective end of organized Cathar resistance in the Languedoc region.

In May 1243, a massive force of about 10,000 royal troops, led by the seneschal Hugues des Arcis, surrounded the fortress of Montségur. The castle, perched atop a steep limestone rock, had become the last major stronghold of the Cathars, housing approximately 500 people, including around 200 perfecti – the spiritual elite of the Cathar faith.

The initial strategy of the besiegers was to starve out the defenders, but Montségur proved remarkably resilient. Well-supplied and supported by the local population, the castle’s inhabitants managed to keep their supply lines open, even receiving reinforcements during the early stages of the siege.

Frustrated by the lack of progress, the crusaders shifted to a more aggressive approach. The castle’s seemingly impregnable position posed a significant challenge, but a breakthrough came when Basque mercenaries managed to secure a position on the eastern side of the summit. This allowed for the construction of a catapult, forcing the refugees living outside the castle walls to seek shelter inside, straining the fortress’s resources.

The siege dragged on through the harsh winter months, with both sides enduring extreme conditions. In January 1244, the tide began to turn against the defenders. Gascon mountain troops, under the cover of darkness, managed to scale the northeastern tip of the pog and capture a crucial position known as the Roc de la Tour. This success allowed the crusaders to bring their siege engines within range of the castle walls.

As bombardment intensified, the situation inside Montségur became increasingly desperate. The terraced habitations outside the fortress walls had to be abandoned, and casualties mounted as stone missiles rained down on the defenders. By the end of February, it was clear that the castle could not hold out much longer.

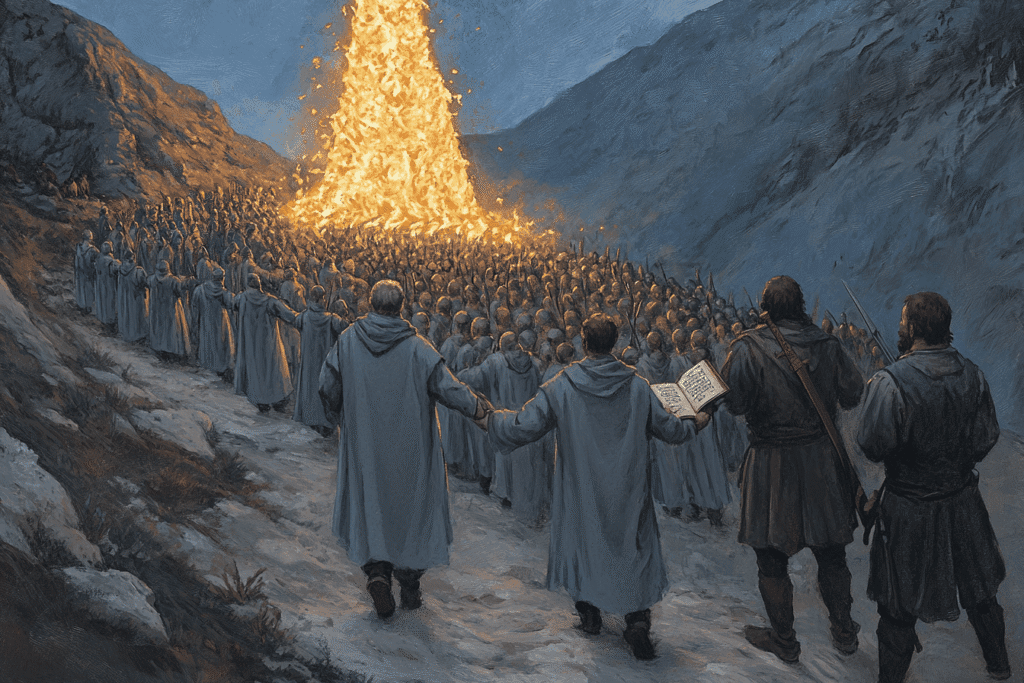

On March 1, 1244, Pierre-Roger de Mirepoix, the military leader of Montségur, emerged to negotiate terms of surrender. A fifteen-day truce was agreed upon, during which the defenders were given a stark choice: renounce their faith or face death by fire.

These final days were marked by intense spiritual preparation among the Cathars. Many of the castle’s inhabitants, including some of the soldiers, chose to receive the consolamentum, the Cathar sacrament that elevated believers to the status of perfecti. This decision effectively sealed their fate, as perfecti were bound by their faith to choose martyrdom over renunciation.

On March 16, 1244, the truce expired. In a display of unwavering faith that would become legendary, more than 200 Cathars – men and women, young and old – voluntarily walked down the mountain to the pyre that had been prepared for them. Led by their spiritual leader, Bishop Bertrand Marty, they entered the flames without resistance, singing hymns as the fire consumed them.

The fall of Montségur sent shockwaves through the Languedoc and beyond. It represented not just a military defeat, but the effective end of Catharism as an organized religion. The courage displayed by the martyrs in the face of certain death left an indelible mark on the collective memory of the region.

In the aftermath, those defenders who had chosen to renounce their faith were allowed to leave, though many, including Raymond de Pereille, the lord of Montségur, would later face the Inquisition. The castle itself was destroyed, its ruins standing as a silent testament to the tragic events that unfolded there.

Conclusion

The Albigensian Crusade stands as a stark reminder of the potential for violence and intolerance in the name of religious orthodoxy. This crusade, unique in its targeting of fellow Christians within Western Europe, set a dangerous precedent for religious persecution. It demonstrated the power of the medieval church to mobilize military forces against perceived internal threats, and the willingness of secular powers to use religious justifications for territorial expansion.

The brutality of the campaign, exemplified by events like the massacre at Béziers and the fall of Montségur, left deep scars on the collective memory of the region. The suppression of Catharism came at an enormous human cost, forever altering the cultural and linguistic character of southern France.