The assassination of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral on December 29, 1170, was a shocking event that sent ripples throughout medieval Europe and had far-reaching consequences for the relationship between Church and State in England. This account will explore the events leading up to the murder, the assassination itself, and its aftermath.

Background and Rise to Power

Thomas Becket was born in London around 1119 or 1120, the son of a merchant. He rose through the ranks of 12th-century government, eventually becoming Chancellor to King Henry II in 1155. Henry trusted Becket and valued his advice, particularly in matters concerning the Church.

When Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died in 1161, Henry saw an opportunity to increase his control over the Church by installing his friend and confidant, Thomas Becket, in this powerful position. In 1162, Becket was rapidly elevated through the ecclesiastical ranks, becoming a priest, then a bishop, and finally the Archbishop of Canterbury in a matter of days!

The Becket Controversy

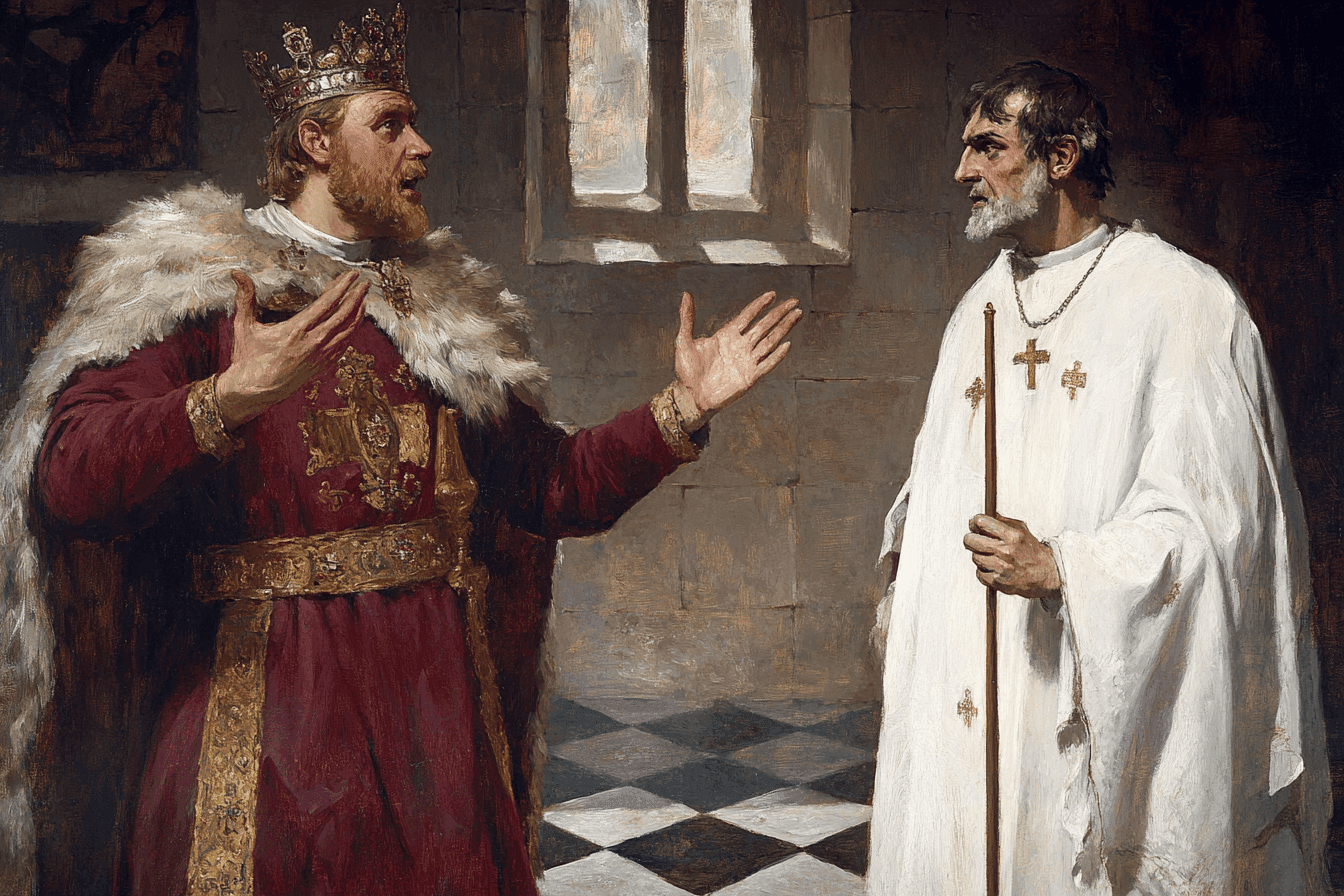

Henry II hoped that by appointing Becket as Archbishop, he would be able to assert royal supremacy over the English Church and regain the rights the crown had held during the reign of his grandfather, Henry I. However, Becket’s new role brought about an unexpected transformation in him, kindling a newfound religious fervor.

The king’s primary goal was to curtail the practice of clerics being tried in religious courts rather than the king’s court. This desire to limit ecclesiastical autonomy set the stage for what would become known as the Becket Controversy or Becket Dispute, a quarrel between the Archbishop and the King that would last from 1163 to 1170.

The controversy centered on the respective rights of the crown and the church. As Henry attempted to reassert royal prerogatives, Becket resisted, defending what he saw as the Church’s rightful autonomy. A significant point of contention was the jurisdiction over criminal cases involving clerics, even those in minor orders.

Escalation of the Conflict

As the dispute dragged on, both sides appealed to the pope, who attempted to broker a negotiated settlement. However, these efforts proved futile, and the conflict continued to escalate. The king resorted to confiscating Church property, while the archbishop issued excommunications against those who opposed him.

In 1164, Henry introduced the Constitutions of Clarendon, a set of legislative procedures designed to curb ecclesiastical privileges and limit the power of church courts. Becket initially agreed to these measures but later recanted, further angering the king.

Faced with charges of contempt of royal authority and malfeasance in his role as Chancellor, Becket fled to France in 1164, where he remained in exile for six years. During this time, the dispute between Becket and Henry II became increasingly bitter, with both sides refusing to compromise.

Return to England and Growing Tensions

In 1170, under threat of excommunication by the pope, Henry allowed Becket to return to England and resume his role as Archbishop of Canterbury. However, the reconciliation was short-lived. Shortly before landing in England in early December, Becket excommunicated Roger of York, Josceline of Salisbury, and Gilbert Foliot, three ecclesiastics who had supported the king during the controversy.

This action infuriated Henry, who was in Normandy at the time. When Roger, Josceline, and Foliot appealed to the king, Henry’s anger reached a boiling point. It was at this moment that Henry allegedly uttered the infamous words that would seal Becket’s fate: “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?”

The Assassination

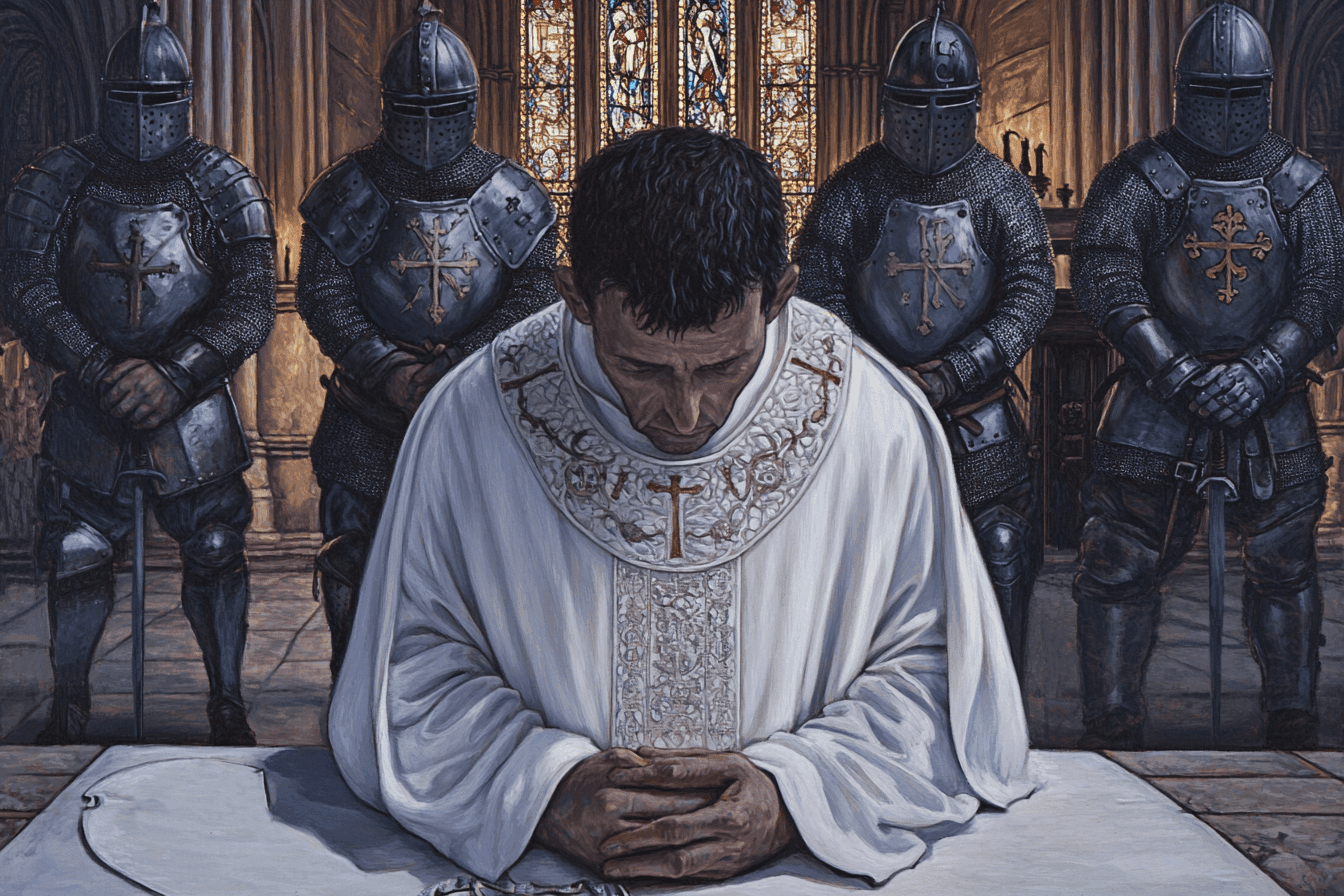

On December 29, 1170, four knights – Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, and Richard le Breton – arrived at Canterbury Cathedral. These men, acting on what they believed to be the king’s wishes, had set out from Henry’s court in Normandy with the intention of confronting the archbishop.

According to Edward Grim, a monk who witnessed the event, the knights entered the cathedral shouting, “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the king and the kingdom?” They found Becket near the altar, where he had been preparing for evening prayers.

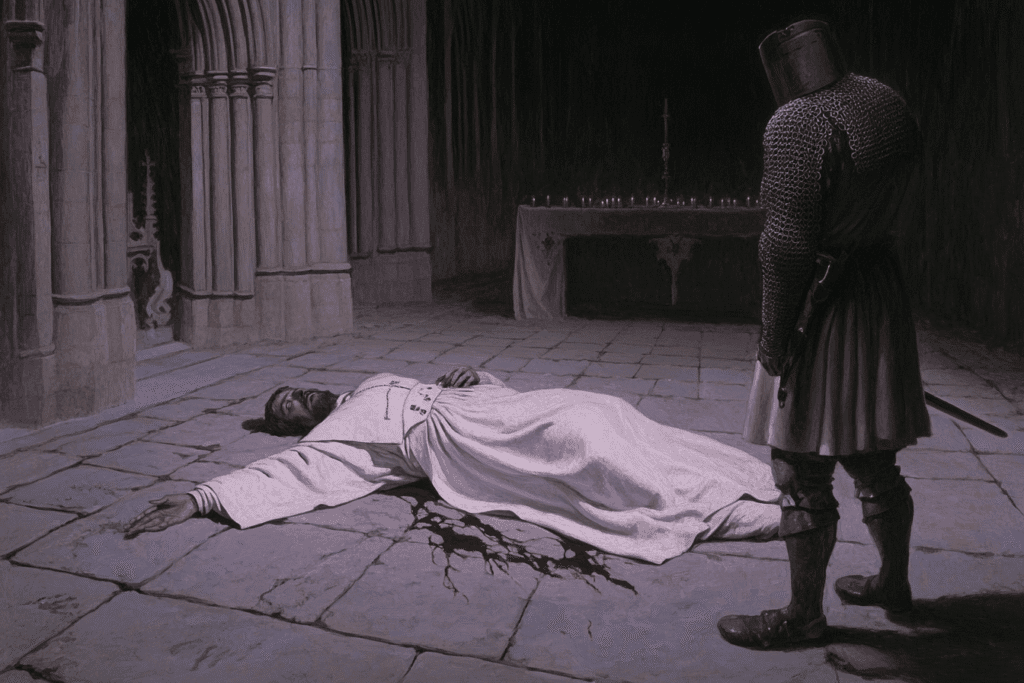

The knights demanded that Becket lift the excommunications he had imposed and submit to the king’s authority. When Becket refused, violence erupted. The assassins attacked the archbishop with their swords, striking him multiple times. Becket’s blood spilled on the cathedral floor as he collapsed, fatally wounded.

The brutal murder of Thomas Becket, carried out in the sacred space of Canterbury Cathedral, shocked the Christian world. The image of an archbishop being slain at the altar would become a powerful symbol of martyrdom and resistance to royal tyranny.

Immediate Aftermath

News of Becket’s murder spread rapidly across Europe, inspiring a cult of followers. The four knights responsible for the assassination fled the scene, traveling to the north of England. They were subsequently excommunicated by the pope but, after seeking forgiveness, were instructed to serve as knights in the Holy Land on Crusades for 14 years.

King Henry II, upon hearing of Becket’s death, was reportedly overcome with remorse. He insisted that he had never intended for Becket to be murdered. The king faced a severe backlash, both from his own subjects and from other European rulers, who were horrified by the sacrilegious nature of the crime.

Canonization and Cult of St. Thomas

The impact of Becket’s murder on popular imagination was immense. Almost immediately, there were reports of miracles occurring at his tomb. People believed that Becket’s blood, spilled on the cathedral floor, had the power to heal the sick.

In 1173, just three years after his death, Pope Alexander III canonized Thomas Becket as a saint. This rapid canonization was a clear indication of the Church’s view of Becket as a martyr who had died defending ecclesiastical rights against royal encroachment.

Canterbury Cathedral quickly became one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Europe. Pilgrims from across the continent flocked to Becket’s shrine, seeking spiritual solace and miraculous cures. The popularity of these pilgrimages would later inspire Geoffrey Chaucer’s seminal work of English literature, “The Canterbury Tales.”

Henry’s Penance

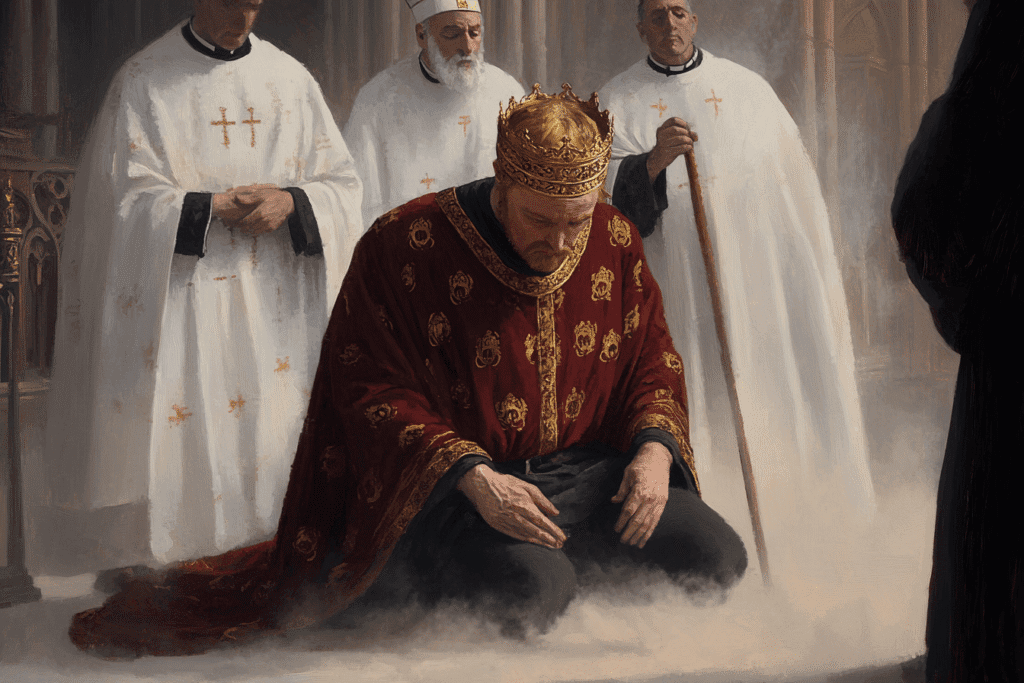

In 1174, King Henry II faced a rebellion from his sons, supported by the French. Viewing this as divine punishment for his role in Becket’s death, Henry undertook a dramatic act of public penance.

The king traveled to Canterbury Cathedral and allowed himself to be whipped by bishops as he prayed at Becket’s tomb. This act of humiliation by one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe was a striking demonstration of the Church’s moral authority and the power of Becket’s martyrdom.

Long-term Consequences

The murder of Thomas Becket had profound and lasting effects on the relationship between Church and State in England. In the short term, it was a significant setback for Henry II’s attempts to assert royal authority over the Church. The king’s plans to curb ecclesiastical power ended in failure, and the Church emerged from the controversy with its privileges largely intact.

In the longer term, the Becket affair contributed to a gradual shift in the balance of power between the monarchy and the Church. The image of a king humbling himself before the tomb of a martyred archbishop became a powerful symbol of the limits of royal authority.

The controversy and its bloody conclusion also played a role in the events leading up to the signing of Magna Carta in 1215. The murder of Becket had demonstrated the dangers of unchecked royal power and contributed to the growing demand for formal limitations on the king’s authority.