The Sultanate of Rum, a medieval Sunni Muslim state, played a pivotal role in shaping the history and culture of Anatolia during its existence from 1077 to 1308. Often overshadowed by the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, this Turco-Persian state emerged as a dynamic force in the region, blending traditions from the Islamic world with Byzantine influences.

Origins: From Seljuk Roots to Independence

The Sultanate of Rum traces its roots to the Seljuk Turks, a nomadic people from Central Asia who embraced Islam in the 10th century. Their westward expansion brought them to the Byzantine empire and culminated in the decisive Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

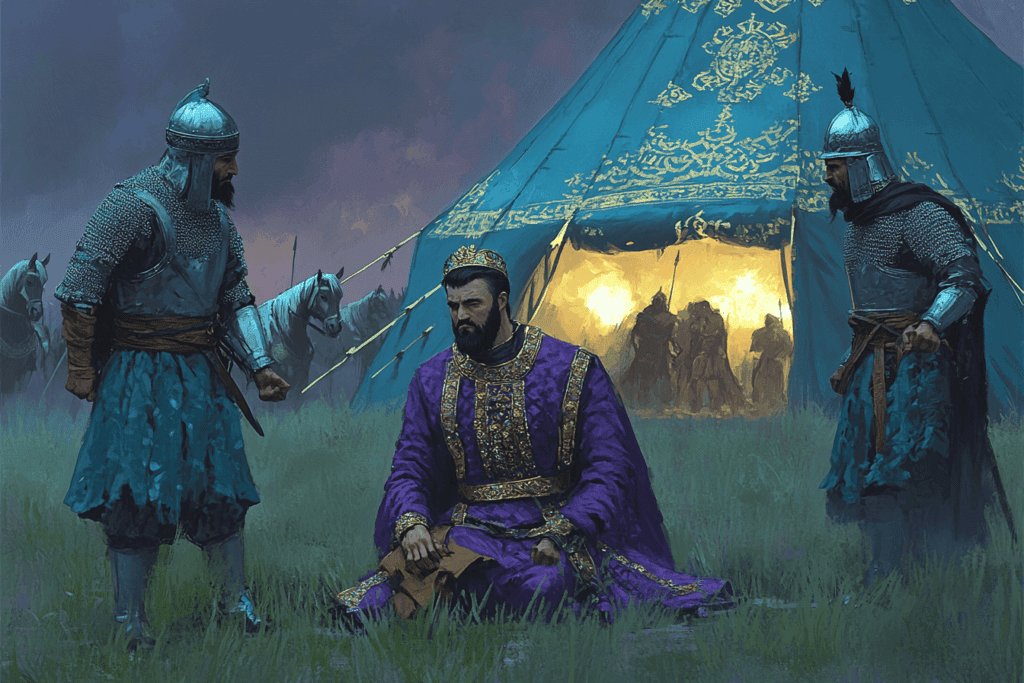

The battle was fought between the forces of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes and the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan. Romanos sought to halt Seljuk incursions into Byzantine territory and restore imperial authority in the east, but internal divisions and strategic missteps led to catastrophe.

The Byzantine army was composed of professional soldiers, mercenaries, and levies, but its cohesion was undermined by treachery. Key commanders defected, including Andronikos Doukas, whose betrayal sealed Romanos’s fate. Alp Arslan’s forces employed classic steppe tactics—horse archers in crescent formations—harassing the Byzantines and feigning retreats to lure them into disarray. By nightfall, confusion gripped the Byzantine ranks, leading to their encirclement and destruction.

Romanos was captured, becoming the only Byzantine emperor taken prisoner by a Muslim commander. Although Alp Arslan released him after securing territorial concessions, Romanos returned to a hostile court. He was overthrown, blinded, and ultimately killed—a grim symbol of Byzantium’s political instability.

In the aftermath, the Seljuks rapidly occupied much of Anatolia, paving the way for Turkic migration and eventual Ottoman ascendancy. Byzantium’s weakened state prompted appeals to Western Europe for aid, setting the stage for the First Crusade. Initially based in Nicaea (modern İznik), the Sultanate symbolically adopted the name “Rum,” referencing the Roman (Byzantine) legacy it sought to inherit.

The Battle of Myriokephalon

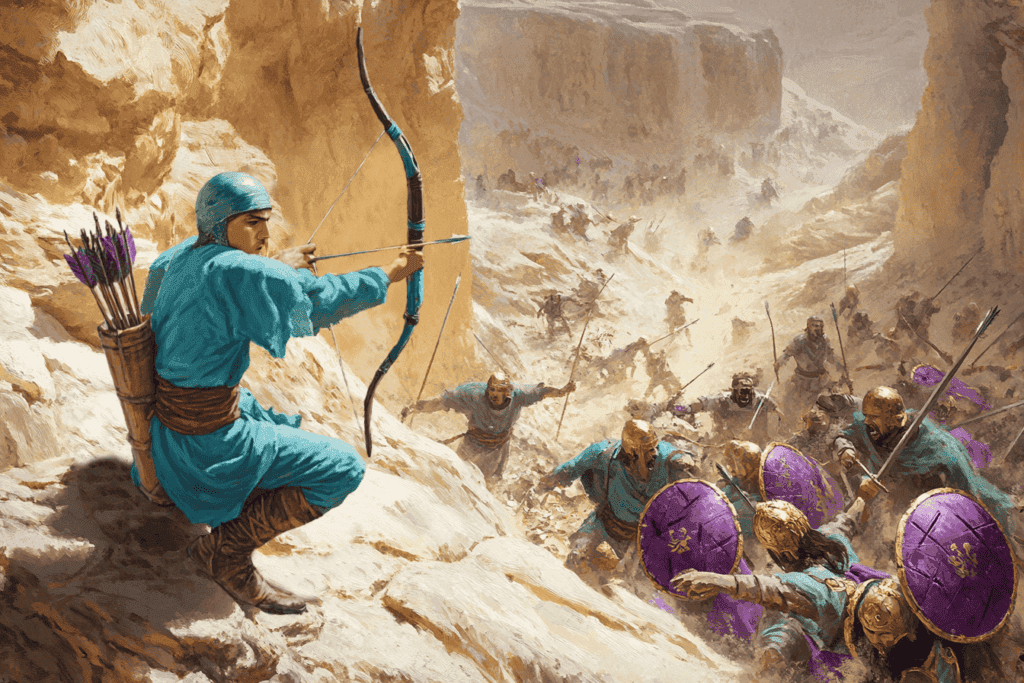

Five years after the Battle of Manzikert, another emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, led a massive Byzantine army against the Seljuk Turks, aiming to capture their capital, Iconium (modern-day Konya), and reassert control over central Anatolia. Manuel’s forces, estimated at 25,000–35,000 strong, advanced through the narrow mountain pass of Myriokephalon near Lake Beyşehir.

The Seljuks had prepared an ambush, exploiting the terrain to devastating effect. Manuel’s army, stretched into a vulnerable column over ten miles long, failed to properly scout ahead or maintain cohesion. As the Byzantine divisions entered the defile, Seljuk archers rained down arrows from the heights, targeting both soldiers and siege equipment. The Byzantine right wing collapsed under heavy assault, while their baggage train was destroyed, leaving them immobilized and disorganized.

The defeat shattered Manuel’s confidence and forced him to negotiate peace with Kilij Arslan. Although the Byzantines retained their core military strength, they abandoned their ambitions in Anatolia. This battle cemented Turkish dominance over Anatolia.

Administrative Structure: A Blend of Traditions

Suleiman’s leadership marked the beginning of Turkish dominance in Anatolia. He distributed land among his followers according to Turkic traditions, revitalized local economies, and reduced taxes on peasants who had suffered under Byzantine rule. This pragmatic approach ensured stability and laid the foundation for a prosperous state.

The Sultanate of Rum was governed as a monarchy with a strong centralized administration. The sultan held absolute authority but delegated power to provincial governors known as emirs or walis. These officials managed taxation, maintained order, and ensured loyalty to the sultan. What set the Sultanate apart was its legal system—a fusion of Islamic law (Sharia) and Byzantine traditions. Non-Muslim populations were allowed to retain their legal customs, fostering coexistence in a culturally diverse region.

This administrative sophistication contributed to the Sultanate’s longevity, even as it faced external threats like Crusaders and rival Turkish states.

The Crusades and Byzantines

The Sultanate of Rum played a significant role in resisting external invasions during its history. It faced challenges from Crusaders during the First (1096–1099), Second (1147–1149), and Third Crusades (1189–1192). Despite losing Nicaea during the First Crusade, subsequent rulers like Mesut I successfully repelled Crusader forces at battles such as Dorylaeum (1147) and Laodicea (1147).

Religious Dynamics: Sunni-Shia Tensions

Anatolia under the Sultanate was religiously diverse. While Sunni Islam was predominant in urban centers, Shi’ism found support among nomadic Turkic tribes migrating into Anatolia due to Mongol pressure. This diversity led to internal conflicts such as the Alevi uprising led by Baba Ishaq—a movement that nearly toppled the Sultanate.

These tensions persisted into later periods, influencing Ottoman policies toward religious minorities.

Decline: Mongol Invasion and Fragmentation

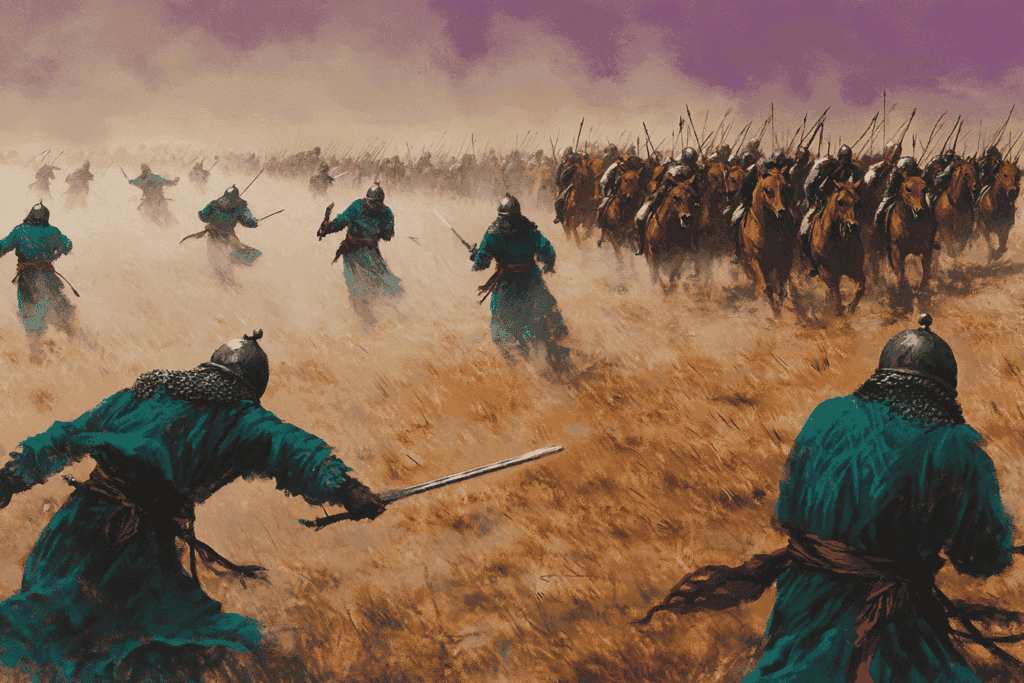

The Sultanate’s downfall began with internal strife following Kilij Arslan II’s death in 1192. His successors struggled to maintain unity among rebellious nobles. The Battle of Köse Dağ, fought on June 26, 1243, was the defining moment.

It pitted the Sultanate of Rum, led by Sultan Kaykhusraw II, against the Mongol forces commanded by Baiju Noyan. Kaykhusraw was dismissive of cautious advice from his experienced nobles, and opted for an offensive strategy at Köse Dağ Mountain near Sivas. He was overconfident having 80,000 Seljuk troops against just 30,000 Mongols. However, the Mongols exploited this rashness with superior tactics.

Baiju skillfully lured the Seljuks into a narrow valley, where their fragmented and undisciplined forces were vulnerable. Utilizing classic steppe warfare techniques, the Mongols feigned retreat, drawing the Seljuks into pursuit before unleashing devastating volleys of arrows followed by a counter-charge. By evening, the Seljuk formation crumbled under sustained pressure. Despite their numerical superiority, the Seljuk army suffered a catastrophic defeat that reshaped the political landscape of the region.

The aftermath was disastrous for Rum. Kaykhusraw fled with his family to Ankara, abandoning his army to disband in chaos. The Mongols captured key cities like Sivas and Kayseri and imposed heavy tributes on the Sultanate, reducing it to a client state. This defeat marked the end of Seljuk autonomy, as it became a vassal state forced to pay tribute. Neighboring states like Cilician Armenia and Trebizond quickly submitted to Mongol rule.

Mongol domination led to arbitrary taxation that fueled resistance movements across Anatolia. Independent beyliks (Turkish principalities) emerged as central authority weakened. By 1308, Konya was annexed by the Karamanids—marking the end of the Sultanate.

Legacy: A Bridge Between Empires

Though it ceased to exist politically, the Sultanate’s cultural legacy endured. Its architectural innovations influenced Ottoman designs; its promotion of Islam paved the way for Anatolia’s transformation into a predominantly Muslim region, although other religions were tolerated.

The Ottoman Empire itself emerged within territories once controlled by Rum—a testament to its foundational role in shaping Turkish history.