The “mayor of the palace” began as the chief steward of the royal Frankish household. Over time, as Merovingian kings became increasingly young, inept, or uninterested in ruling, the mayors took on greater responsibilities, including military command, until they usurped their royal masters.

Origins: The Chief Steward

In the 6th century, the Merovingian kings ruled over a vast and diverse Frankish realm. The king’s court was not a fixed institution but traveled with the monarch, and the palace was wherever the king resided. The complexity of managing the royal household and the broader administration of the kingdom led to the appointment of a chief steward, known as the mayor of the palace (maior domus).

Initially, the mayor was responsible for the domestic affairs of the palace: managing servants, overseeing the royal estates, and ensuring the smooth operation of the court. The office was filled by appointment from among the most powerful noble families, reflecting the rising influence of the aristocracy in Merovingian society.

Expansion of Duties and Power

As the Merovingian kingdom grew, so did the responsibilities of the mayor. The king relied increasingly on the mayor to handle not just the household, but also the administration of the realm, including the collection of taxes, management of royal lands, and even the granting of beneficia (early fiefs) to secure the loyalty of powerful nobles.

The mayor also became the chief intermediary between the king and the magnates, controlling access to the monarch and brokering political interests at court. With the king often distracted by personal pleasures or hampered by youth and inexperience, the mayor shouldered more burdens, gradually drawing real power into his own hands.

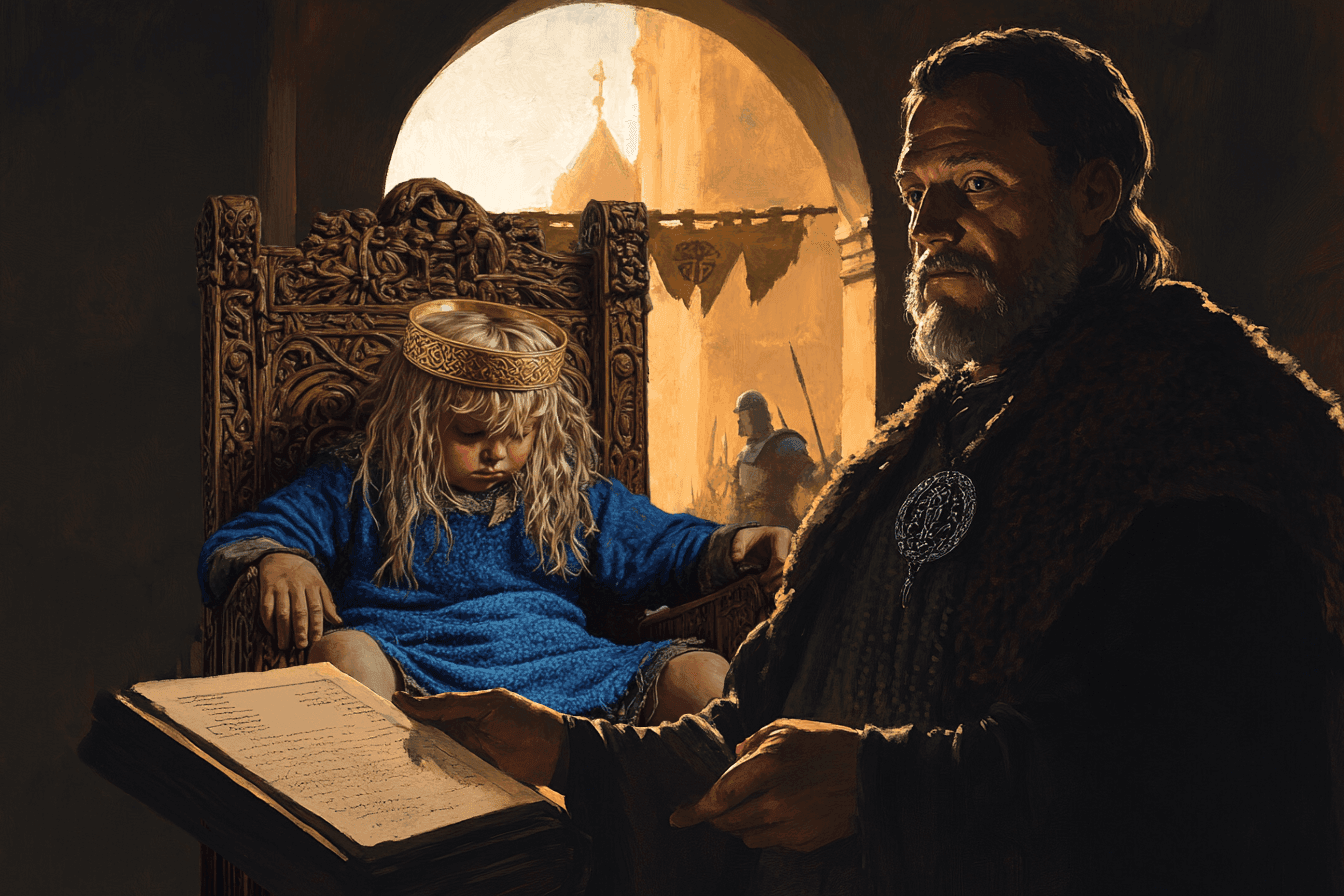

The Rise of the “Do-Nothing Kings”

By the late 7th century, the Merovingian dynasty was plagued by a series of weak or child monarchs. These so-called rois fainéants (“do-nothing kings”) were often mere figureheads, with the real authority exercised by the mayors of the palace. The aristocracy, entrenched in their own power bases, further eroded royal authority, and the mayors became the effective rulers of the realm.

In this period, the mayors did not simply manage the court—they directed the administration, commanded armies, and made decisions that shaped the destiny of the Frankish people. The king, meanwhile, was reduced to a ceremonial role, sometimes receiving only a living allowance determined by the mayor.

Regional Rivalries and the Triumph of Austrasia

The Frankish kingdom was divided into regions, each with its own mayor: Austrasia in the east, Neustria in the west, and Burgundy in the south. These regions often competed for supremacy, and their mayors became rivals, leading to frequent civil wars.

The turning point came in 687, when Pepin of Herstal, the mayor of Austrasia, defeated his Neustrian rivals at the Battle of Tertry. This victory marked the beginning of Austrasian dominance and the effective rule of the Arnulfing-Pippinid family, ancestors of the Carolingians. Mayor Pepin took the title “Duke of the Franks” and ruled as the de facto sovereign, though he never claimed the royal title.

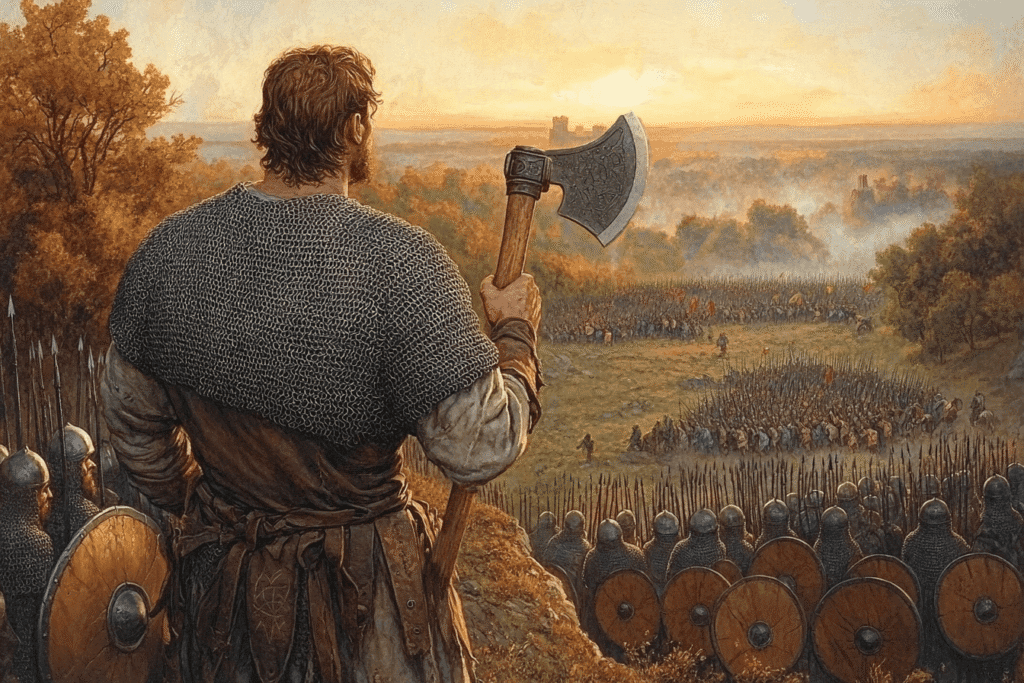

The Mayors as Military Commanders

The growing military responsibilities of the mayor were crucial to their rise. As external threats mounted—from the Saxons in the north to the Moors advancing from Spain—the mayors led armies, defended the realm, and expanded Frankish power. Charles Martel, son of Pepin of Herstal, became legendary for his victory over the Moors at the Battle of Tours in 732, a feat that secured his reputation as the savior of Christendom and cemented the military authority of the mayor.

Charles Martel ruled without appointing a new king during the last years of his life, demonstrating that the office of mayor had become synonymous with real sovereignty.

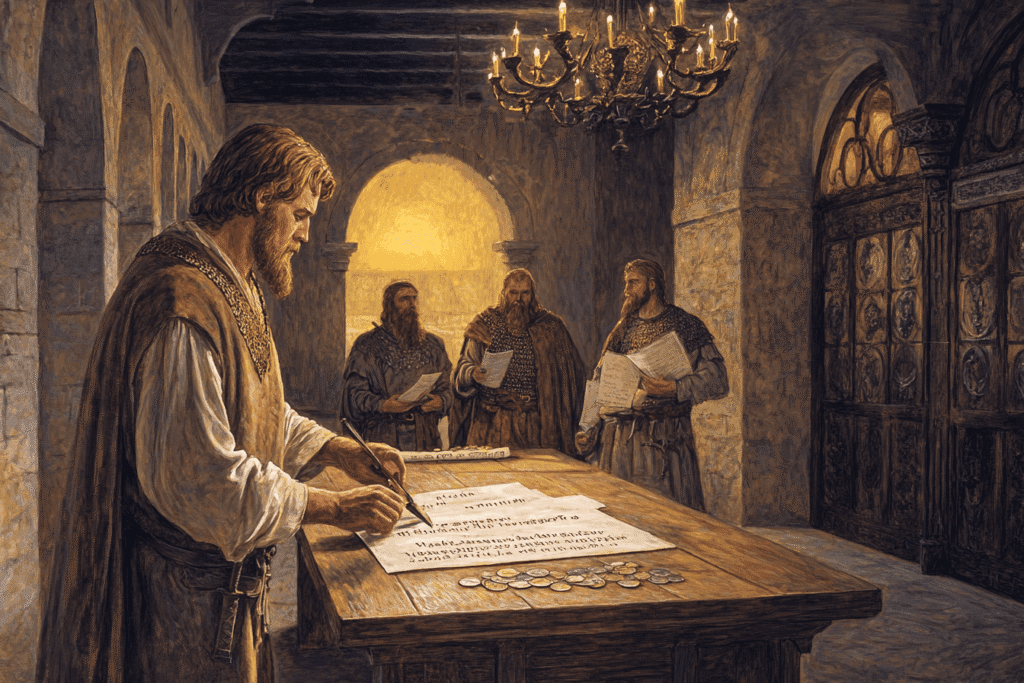

From Mayor to Monarch: The Carolingian Revolution

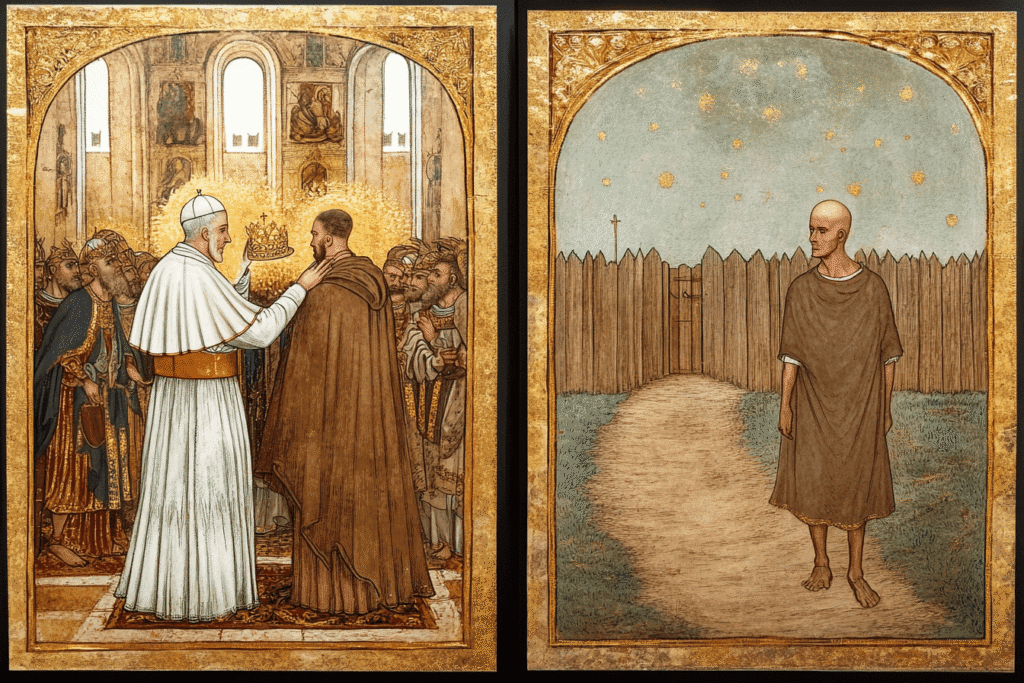

After Charles Martel’s death, his sons Carloman and Pepin the Short continued to rule as mayors, keeping the Merovingian king as a puppet. Eventually, Pepin decided to formalize the reality of power by seeking the support of the papacy. By the mid-8th century, the fiction of Merovingian rule had worn thin. In 751, with the blessing of Pope Zachary, Pepin deposed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, and was crowned king himself, inaugurating the Carolingian dynasty.

Childeric was tonsured (his long hair, a symbol of royal power, was cut) and sent to a monastery, marking the end of Merovingian rule and the absorption of the mayoralty into the kingship.

The Pippinid–Carolingian Ascendancy

The transformation of the office into a hereditary power base began with the Pippinid family. Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, decisively defeated his rivals at the Battle of Tertry in 687, uniting Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy under his effective rule as “Duke of the Franks”.

His successors, notably his son Charles Martel, further consolidated this power. Charles Martel ruled without even bothering to install a Merovingian king for several years, acting as the undisputed leader of the Franks. He passed his power to his sons, Carloman and Pepin the Short, who continued to rule as mayors with the king as a mere puppet.

The End of the Merovingians and Birth of the Carolingians

In 751, Pepin the Short, with papal approval, deposed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, and had himself crowned king, founding the Carolingian dynasty. This marked the final transformation of the mayoral office from royal servant to monarch, a dramatic shift in Frankish history.

The rise of the mayor of the palace from household manager to kingmaker – and finally to king – was a defining moment of the Frankish empire. It was a story of political acumen, military strength, and the gradual eclipse of royal authority by ambitious nobles who became the architects of a new order.