Reading it feels like uncovering a lost manuscript, one that’s worth translating and understanding.

If you’re fascinated by the Norman Conquest, the fading twilight of Anglo-Saxon England, or the cultural upheavals that shaped the island’s identity, then Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake is a novel you need to read, though be warned: it’s not like anything else on your bookshelf.

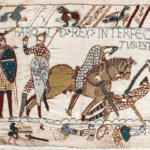

Set in the aftermath of 1066, The Wake plunges us deep into the mind of Buccmaster of Holland, a proud, angry, increasingly unhinged Lincolnshire freeman who watches his world collapse after the Norman invasion. With his lands seized, his sons killed, and his sense of order shattered, Buccmaster takes to the fens and marshes to wage a personal war of vengeance. He becomes a self-styled “grene man,” leading a ragtag band of guerrilla fighters in the name of lost gods and shattered oaths.

Sound like historical fiction? It is – but not in the conventional sense.

A Language Rebellion

The first thing you’ll notice – and perhaps the most talked-about feature of the book – is its language. Kingsnorth has written The Wake in what he calls a “shadow tongue”: a sort of invented Old English-inflected English that evokes the sounds and rhythm of Anglo-Saxon speech while remaining (mostly) intelligible to modern readers. Here’s a taste:

“i seen now what it is for a man to have his worold broc. i seen now what is the angland of efry man. i seen now what is the triew gods.”

At first, this can be jarring – even frustrating. But once you tune your ear to the voice, it becomes immersive. This isn’t just a stylistic gimmick; the language is integral to the book’s themes. The world Buccmaster knew is gone, and he’s narrating his own cultural and personal apocalypse in a tongue that feels like it’s clinging to the edge of memory. Reading it feels like uncovering a lost manuscript.

History from the Inside

Many novels set during the Norman Conquest – especially those we tend to find in the historical fiction shelves – give us sweeping accounts of kings, battles, and political machinations. The Wake takes the opposite approach: it’s a claustrophobic, intensely psychological tale told from the margins. We don’t see Hastings. We don’t meet William. Instead, we get a deeply unreliable narrator whose sense of self is tied to a world order that no longer exists.

Buccmaster is not a likable hero. He’s proud, wrathful, arrogant, xenophobic, and often cruel. But he’s also human. Kingsnorth isn’t asking us to root for him uncritically – he’s asking us to understand what it feels like to be on the wrong side of history. The Norman Conquest, for Buccmaster, is not a new chapter in England’s story – it’s the end of the world. And in a way, it was.

The Slow Death of Anglo-Saxon England

What The Wake captures so brilliantly is the slow death of conquest – the way a culture is hollowed out, how language, memory, religion, and identity are eroded over time. It’s not just about battles and burning villages (though there is violence here). It’s about the grief of watching familiar ways vanish, your status turned to dust, your voice lost.

Buccmaster sees himself as a guardian of the “triew angland,” a land of ancient freedoms and gods like Woden and Thunor. But we, the readers, can see how much of this “true England” is already myth, half-remembered and romanticized. His resistance is both tragic and futile – but in that futility lies the novel’s emotional weight.

A Book for the Patient and the Passionate

Make no mistake: The Wake is a demanding read. The language, the pacing, and the lack of conventional narrative structure mean it’s not a book to breeze through on a weekend. But for readers who love this period of history – especially those who’ve read about Hereward the Wake, the Harrying of the North, or the lingering Anglo-Danish resistance in the fens – it’s a rewarding, haunting experience.

In fact, Kingsnorth’s Buccmaster is often read as a fictionalized echo of Hereward, though darker and more psychologically unmoored. Where most retellings of post-Conquest rebellion romanticize the resistance, The Wake explores its moral complexity and emotional cost.

Final Thoughts

The Wake isn’t your typical historical novel. It’s a raw and unsettling account of cultural dislocation, and a bold literary experiment that succeeds on its own uncompromising terms.

For readers interested in the Anglo-Saxon period, the Norman Conquest, and the idea of Englishness itself, The Wake offers something rare: a story that feels rooted in the period, not just draped in its aesthetics. It doesn’t reconstruct the past – it lets you feel what it might have meant to live through its violent unraveling. If you’re willing to immerse yourself in its language, The Wake will leave a mark.