By the end of the 5th century AD, Latin – the language used for the administration of the Roman Empire – was no longer what it used to be. In its place, a growing patchwork of regional dialects was emerging. These new varieties of speech, though still recognizably Latin in origin, were beginning the slow evolution into what we now know as the Romance languages: Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, and others.

But how did this transformation happen? And why, at the moment when Latin seemed most entrenched – enshrined in law, literature, religion, and administration – did it begin to break apart?

Latin: From Forum to Fortress

Latin began its imperial life as the language of the Roman Republic’s legal and military machine. As Rome expanded, Latin spread, gradually replacing or coexisting with local languages across Italy, Gaul, Iberia, and North Africa. By the 2nd century AD, Latin was entrenched across the western half of the empire, especially in urban centers.

But Latin wasn’t monolithic. There were already two major registers:

- Classical Latin, the literary language of Cicero, Virgil, and Tacitus – learned, standardized, elegant.

- Vulgar Latin (from vulgus, “the common people”), the spoken, ever-shifting language of daily life.

This spoken Latin, not the version taught in elite schools, was the ancestor of the Romance languages. As long as the empire remained relatively stable, Classical Latin continued to dominate writing and education, while Vulgar Latin adapted to the streets, markets, and villages. But that balance began to tip in the 4th century – and by 390 AD, cracks were showing.

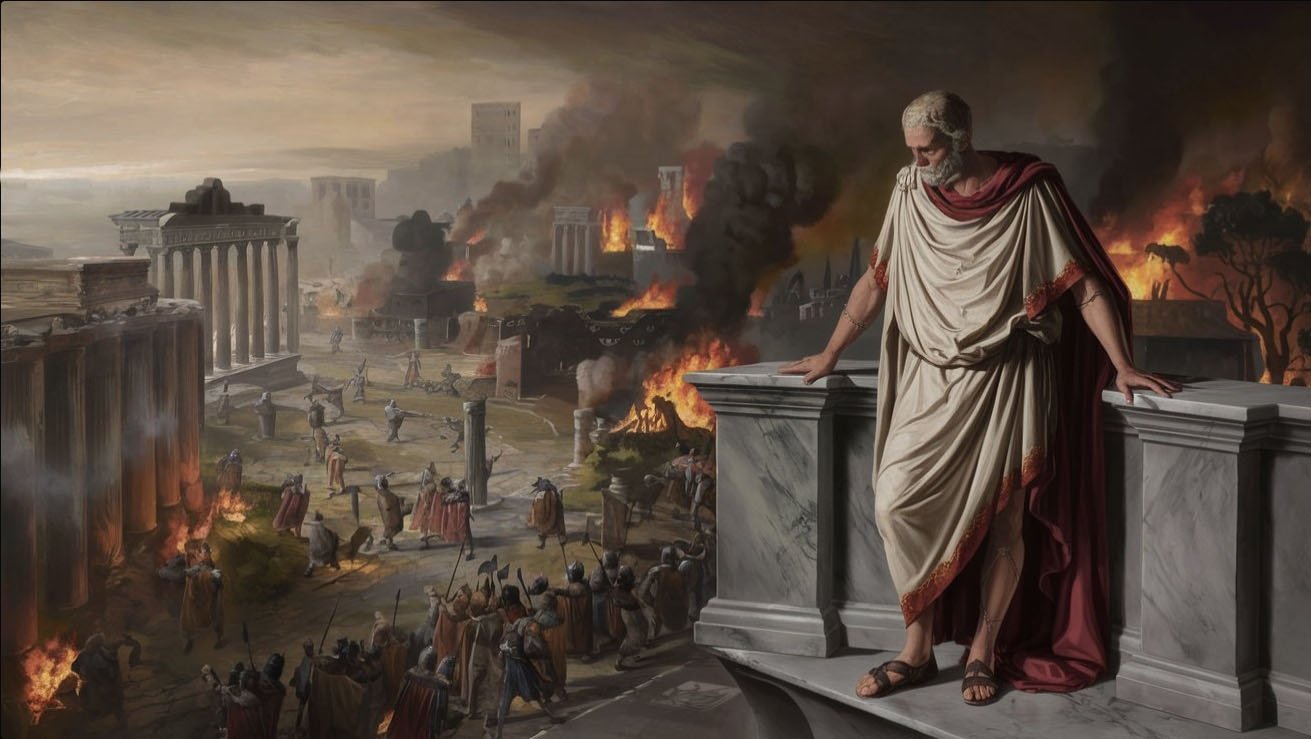

Barbarians at the Gates – and Inside Them

The late 4th and 5th centuries saw massive migrations of Germanic and other non-Latin-speaking peoples into the empire: Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Alans, Burgundians, Franks. Many settled as foederati (allied peoples), nominally under Roman control but increasingly autonomous.

These groups brought with them their own languages – Gothic, Frankish, Vandalic – and although they learned Latin to navigate administration and trade, they influenced its spoken form profoundly.

Think of a frontier town in Gaul, where Roman veterans speak rough Latin, traders speak Punic or Greek, and Gothic mercenaries are trying to learn enough Latin to negotiate pay. Language, here, is messy, hybrid, and in flux.

In these multilingual melting pots, grammar weakened, vocabulary shifted, and pronunciation blurred. Over time, this led to the divergence of dialects.

The Collapse of Education

One of the greatest threats to Latin’s stability was the decline of classical education.

In the early empire, education was widespread among the elite. Boys (and some girls) learned Latin grammar, rhetoric, and literature from early childhood. But by the 5th century, the school system was crumbling – especially in the western provinces.

Cities lost revenue. Teachers fled. Libraries were looted or closed. Fewer and fewer people could write in grammatical Latin, and fewer still could read the classics.

This meant that Classical Latin lost its role as a cultural unifier. People still spoke Latin – but without formal training, they spoke and wrote in the vernacular, with increasing variation.

Clerics, not orators, became the new teachers – and their Latin was deeply influenced by the Bible, by translation Greek, and by pastoral simplicity. A new style, “Christian Latin,” emerged – practical, often awkward, and full of innovations.

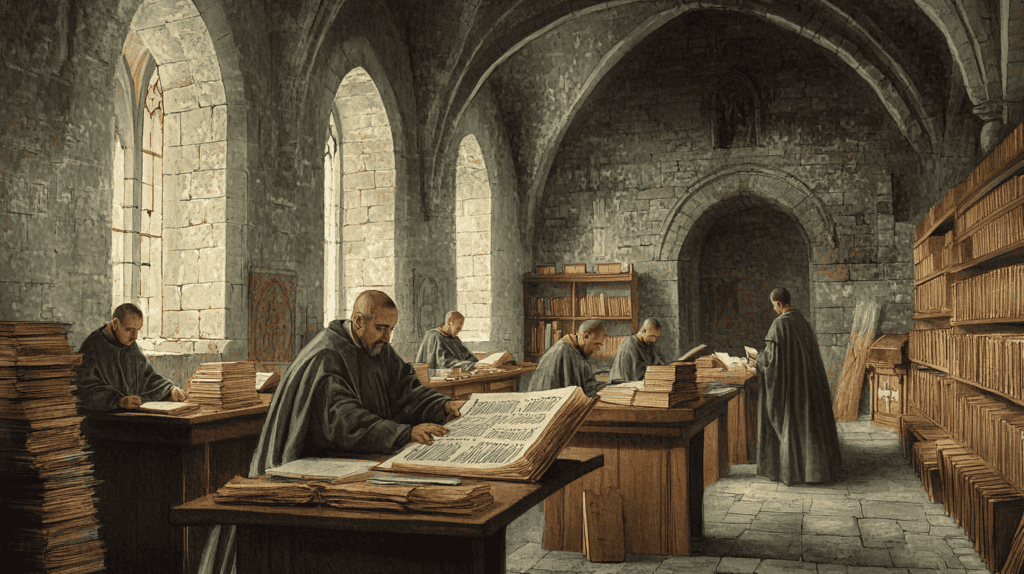

Christianity’s Curious Role

Christianity played a paradoxical role in the decline of Latin.

On one hand, it preserved the language: Church councils, canon law, and theological treatises were written in Latin. Monasteries copied Latin texts, even after the Western Empire collapsed. But on the other hand, Christianization also contributed to the shift toward simpler, less formal Latin.

Early Christian writers like Tertullian, Jerome, and Augustine reached broad audiences, often choosing clarity over elegance. Their Latin was functional, personal, and sometimes infused with biblical Greek. Sermons, homilies, and hymns were composed in Latin forms much closer to the spoken tongue of the people.

In the provinces, bishops and priests often came from the local population – not the Roman elite. They spoke and wrote in regional variants of Latin, which accelerated dialectical divergence.

Cities Shrink, Roads Crumble, Isolation Grows

As the empire fractured, so too did its infrastructure. Roads, aqueducts, and postal systems deteriorated. Trade networks shrank. The great cities of the West – Lugdunum (Lyon), Augusta Treverorum (Trier), Carthago (Carthage) – declined or were sacked.

Urban collapse led to cultural isolation. A Latin speaker in northern Gaul might go their whole life without hearing the Latin spoken in southern Italy or the Pyrenees. Without mobility, dialects ossified.

Compare this to the Roman heyday, when soldiers, merchants, and bureaucrats moved constantly across the empire, spreading and stabilizing Latin. That world was gone.

The Sound of Change: Phonological Drift

Even before the empire fell, spoken Latin was changing phonetically. Here’s what began to happen in the 4th and 5th centuries:

- Loss of final -m: lupum → lupo

- Short vowels merging: i and e, o and u became harder to distinguish

- Reduction of case endings: Word order and prepositions took over from inflected forms

- Palatalization: Latin caelum (“sky”) pronounced more like chélum in some regions

- Diphthong shifts: ae and oe became simple e

These changes varied by region. In Iberia, for instance, some shifts happened faster or more drastically than in Gaul or North Africa.

By the late 5th century, written Latin began reflecting spoken Latin more and more. In short: people were writing Latin as they spoke it, not as they learned it in school. And that spoken language was now regional and variable.

The First Glimpses of the Romance Languages

While no one in 500 AD would say “I speak French” or “I speak Spanish,” the precursors were there.

In Gaul, the Latin spoken by Gallo-Romans and Franks was diverging rapidly. The Council of Tours in 813 (a few centuries later) would famously note that sermons should be delivered in rusticam Romanam linguam—“the rustic Roman tongue”—because people could no longer understand classical Latin.

In Iberia, Latin persisted strongly under Visigothic rule, but Gothic influences crept into vocabulary and pronunciation.

In North Africa, Latin was resilient—used in church and administration—but gradually fell into disuse after the Arab conquest in the 7th century.

In Italy, the heartland of Latin, dialectal differences were slower to emerge, but by the 9th century, regional vernaculars were unmistakably separate from Classical Latin.

What About Greek?

In the eastern empire, Greek was dominant – and remained so. Latin had never replaced Greek in the East. In places like the Balkans, Anatolia, Syria and Egypt, Latin was mostly just used for military and legal purposes. Greek was the working language of traders right across the Roman Empire.

By 500 AD, Greek was the working language of the Byzantine court, education, and church. Latin was still used ceremonially and for some laws, but was retreating fast.

The East-West linguistic split would become a permanent divide – mirrored in the cultural and religious schisms that followed.

Legacy: Latin Dies, But Never Really Dies

By the end of the 5th century, Latin as a unifying spoken language was no more. But it didn’t disappear.

Ecclesiastical Latin survived in the Catholic Church, eventually codified in the medieval period, becoming the language of scholarship, science, and diplomacy in Europe. But beneath all that, the real living legacy of Latin was unfolding in the mouths of peasants, merchants, soldiers, and monks as the Romance languages like French, Spanish, Italian, Catalan, Romanian, Occitan and Portuguese.

Between 390 and 500 AD, Latin didn’t “die” so much as it transformed—quietly, gradually, and irreversibly. The empire fractured. Cities shrank. Invasions came and went. Education faltered. Christianity reshaped culture. Through it all, people still spoke Latin – but not the same Latin, and not the same way. New languages were born from the old. Local, earthy, expressive, and future-bound.