Few figures from the Viking Age have left a legacy as complex and enduring as Olaf II Haraldsson – better known as St. Olaf. Born into a world of Norse gods and warring chieftains, Olaf’s journey from Viking raider to Christian king, martyr, and saint reshaped not only Norway’s destiny but also left a surprising mark on England and beyond.

From Pagan Roots to Christian Zeal

Olaf Haraldsson was born around 995 in Ringerike, Norway, the son of Harald Grenske, a minor king in Vestfold. Like many of his contemporaries, Olaf’s early years were steeped in the traditions of Norse paganism and the violent exploits of Viking raiders.

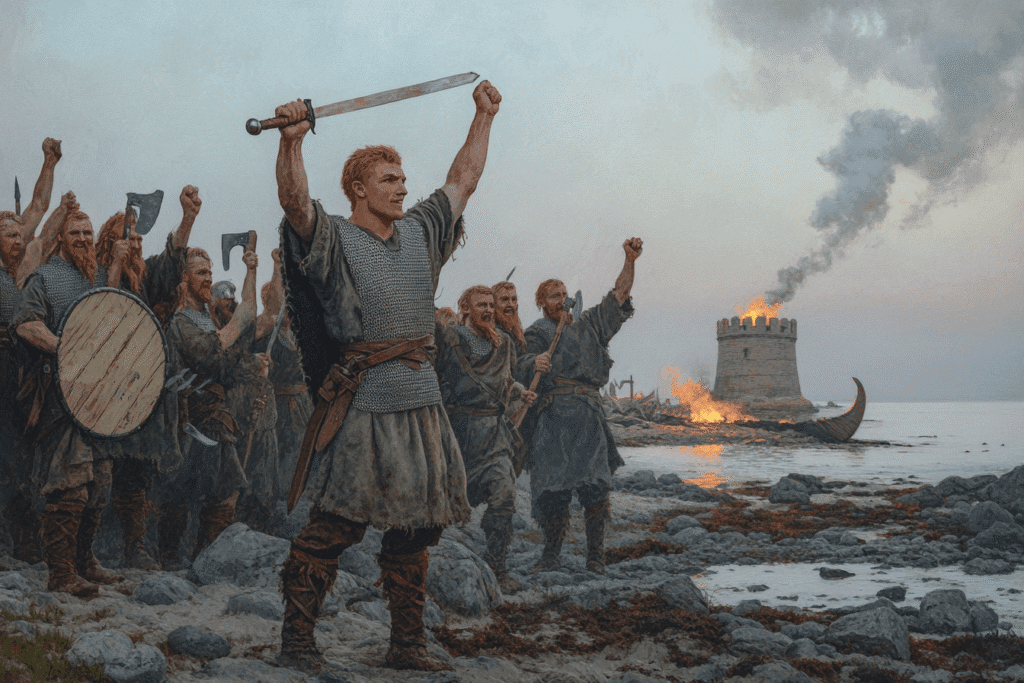

Early Raids in the Baltic and Scandinavia

Olaf’s Viking career began at age 12, a common initiation for Norse nobility. His first targets lay eastward: the Baltic coasts and Finland. Around 1007–1008, he clashed with Finnish tribes at Herdaler (likely in modern-day Uusimaa), where his forces were ambushed in dense forests. The Finns, skilled in guerrilla tactics and reputedly witchcraft, conjured a storm to harry Olaf’s retreat. Despite heavy casualties, he escaped.

Next, Olaf landed on Saaremaa (Osilia), an Estonian island. After initial negotiations collapsed, he crushed the Osilians in battle, securing loot and dominance. These early campaigns honed his tactical acumen, preparing him for larger ventures.

The English Campaigns: Sieges and Betrayals

The following year (1009), Olaf joined forces with Thorkell the Tall, a notorious Danish warlord, to raid England during King Æthelred the Unready’s reign. Their forces attacked Anglo-Saxon London repeatedly, though the city’s fortified bridges and walls resisted capture. Skaldic poetry credits Olaf with destroying London Bridge – a claim absent from Anglo-Saxon chronicles but immortalized in Norse lore.

In 1010, Olaf turned to East Anglia (the eastern coast of England that was frequently raided by vikings) defeating local militias at Ringmere near Ipswich, following which, over a three-month period the Danes wasted East Anglia, burning Thetford and Cambridge. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle laments the slaughter of Æthelred’s allies, including his son-in-law Æthelstan, marking a low point for English resistance.

The following year, Olaf and Thorkell besieged Canterbury, capturing Archbishop Ælfeah. When Ælfeah refused a ransom, the Vikings pelted him to death with animal bones – a grisly act that later haunted Olaf’s conscience.

However in 1012, Æthelred bribed Thorkell into defecting, splitting the Viking coalition. Olaf, now a mercenary for Æthelred, briefly defended England until Sweyn Forkbeard’s invasion in 1013 forced him to flee. This pivot from raider to royal ally hinted at Olaf’s growing political pragmatism.

Raid and Redemption: Brittany, France, and Spain

After leaving England, Olaf sailed south, pillaging Brittany and Normandy. In Rouen, he encountered Duke Richard II, a Christian ruler who may have influenced his religious outlook as Olaf was baptized at Rouen in 1013. This spiritual turning point, however, did not curb his raids.

Olaf’s fleet then struck Galicia and northern Spain, though details remain sparse. Norse sagas suggest he planned a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but a visionary dream – a “terrible man” proclaiming his destiny as Norway’s eternal king – redirected him homeward. Olaf returned to Norway with a new mission: to unite his homeland under the banner of Christ.

Uniting Norway: King and Lawgiver

In 1015, Olaf returned to Norway and declared himself king. Through a combination of military prowess and political cunning, he subdued rival petty kings and defeated his greatest rival Earl Sweyn of Lade at the Battle of Nesjar in 1016, consolidating his rule over a unified Norway.

Olaf’s reign was marked by relentless efforts to Christianize his people. He invited missionaries from England, built churches, and established a national church structure that embedded Christianity into the very fabric of Norwegian society.

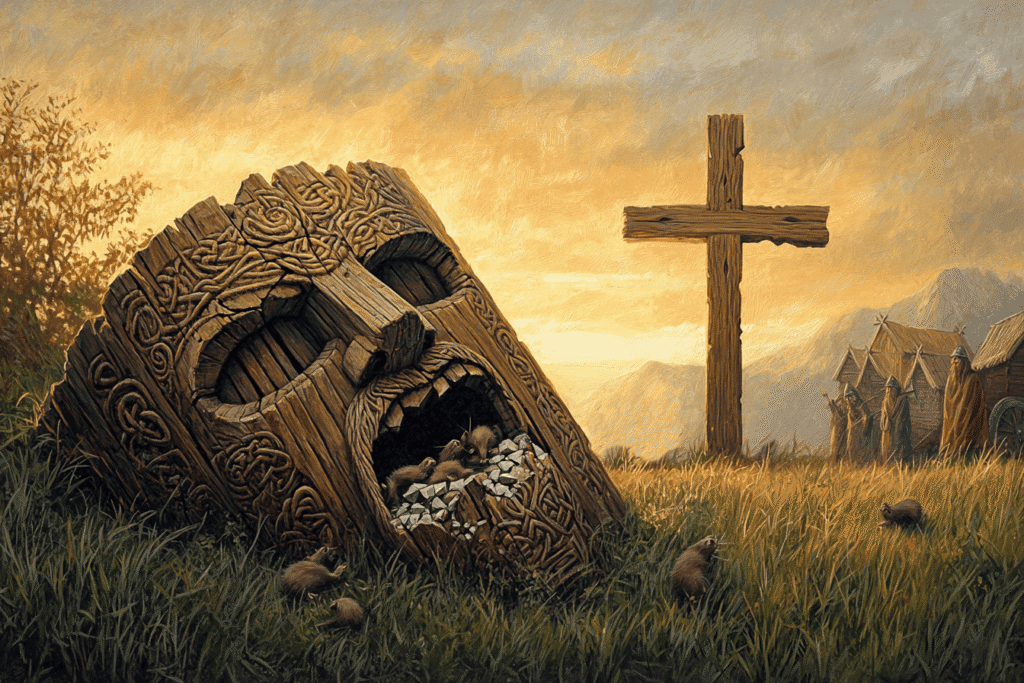

Olaf destroyed pagan temples, outlawed sacrifices, and even starved northern rivals by banning grain sales to them. One iconic episode at Gulbrandsdal saw Olaf challenge a Thor idol. As pagans marveled at a symbolic sunrise (representing Christ), his men smashed the idol, revealing rats and rot-a staged metaphor for paganism’s decay. Such theatrics, combined with brute force, spread Christianity but alienated traditionalists, sowing seeds for his downfall.

One of Olaf’s most lasting contributions was the introduction of a religious code at the Synod of Moster in 1024, Norway’s first national legislation. This code not only mandated Christian worship but also introduced the concept of equality before the law, a radical departure from the old Norse legal traditions. For the next 500 years, Norwegian law would be known as St. Olaf’s Law – a testament to his enduring influence.

Conflict, Exile, and Martyrdom

Olaf’s zeal for Christianization and his sometimes harsh rule alienated many of Norway’s powerful nobles. By 1028, discontent among the aristocracy reached a boiling point. With the support of King Canute the Great of Denmark, the nobles rebelled, forcing Olaf into exile in Kievan Rus. During his time in exile, Olaf is said to have led a monastic life, devoted to prayer and fasting, and even baptized many locals in Sweden’s province of Nerike.

The Battle of Stiklestad

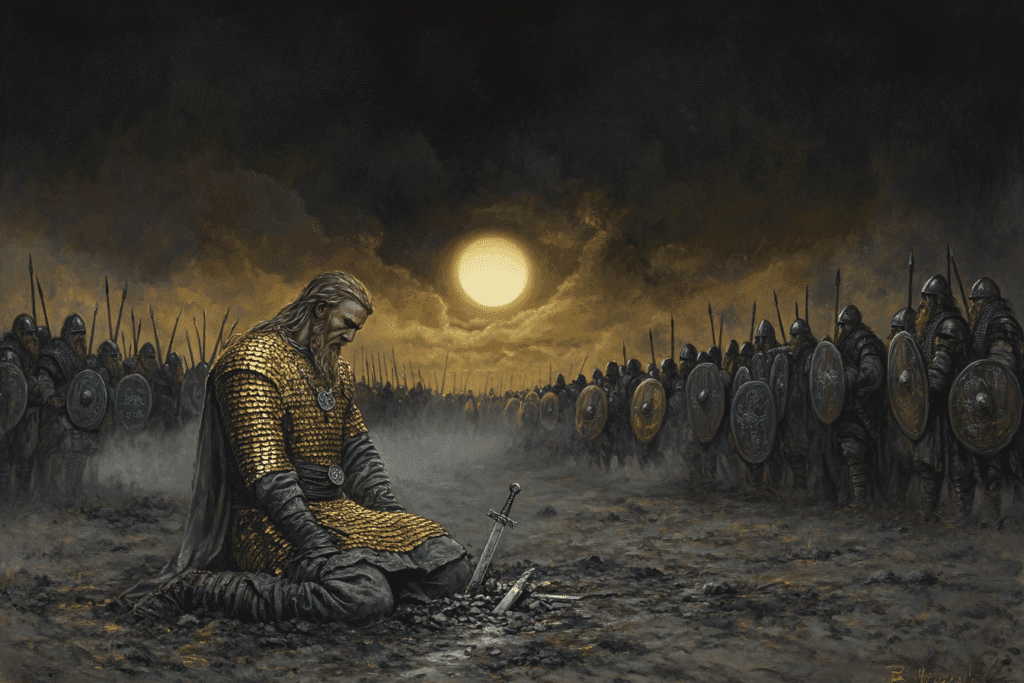

In 1030, Olaf saw an opportunity to reclaim his throne. With support from King Anund Jacob of Sweden, he returned to Norway, only to face a formidable coalition of Danish forces under King Cnut the Great and a vast Norwegian peasant levy. Olaf’s smaller army of loyalists faced his foes at Stiklestad, a site named for a legendary shield-maiden, where faith and fate collided under a mysteriously darkened sky.

Olaf, armored in gold-accented mail and wielding the sword Hneitir, deployed his forces in the Viking wedge formation (svinfylking) to split the enemy line. His speech before battle blended earthly rewards with heavenly promises: “I swear I will not flee… but triumph or die”. The initial charge, described as a “headsman’s axe” blow, shattered the peasant ranks. However, one of the the local Norwegian leaders Thorir Hund, clad in reindeer hide armor believed to be magically charmed, led the cry “Fram, fram, buandmenn!” as his forces enveloped Olaf’s wedge.

The battle’s turning point came as the sky turned “dark as night” – likely a reference to the solar eclipse now dated to August 31, 1030. Amidst the chaos, Olaf was struck down, reportedly uttering the words, “God help me,” as he died. His banner-bearer Thord Folason planted the serpent standard defiantly before falling, while Olaf’s teenage half-brother Harald (later Hardrada) narrowly survived, foreshadowing his own legendary fate at Stamford Bridge in 1066.

The Making of a Saint

Olaf’s death marked a turning point. Though he had been a controversial figure in life, stories of miracles at his tomb quickly spread. It was said that his blood healed the wound of one of his killers and restored sight to a blind man. A year after his death, Bishop Grimketel exhumed Olaf’s body and found it incorrupt – a sign of sainthood in medieval Christianity. Olaf was canonized in 1031, and his remains were enshrined in Nidaros (modern Trondheim), where the great Nidaros Cathedral would later rise above his grave.

Pope Alexander III confirmed Olaf’s sainthood in 1164, making him a recognized saint of the Catholic Church. He became known as Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae – the Eternal King of Norway.

St. Olaf’s Impact on Norway

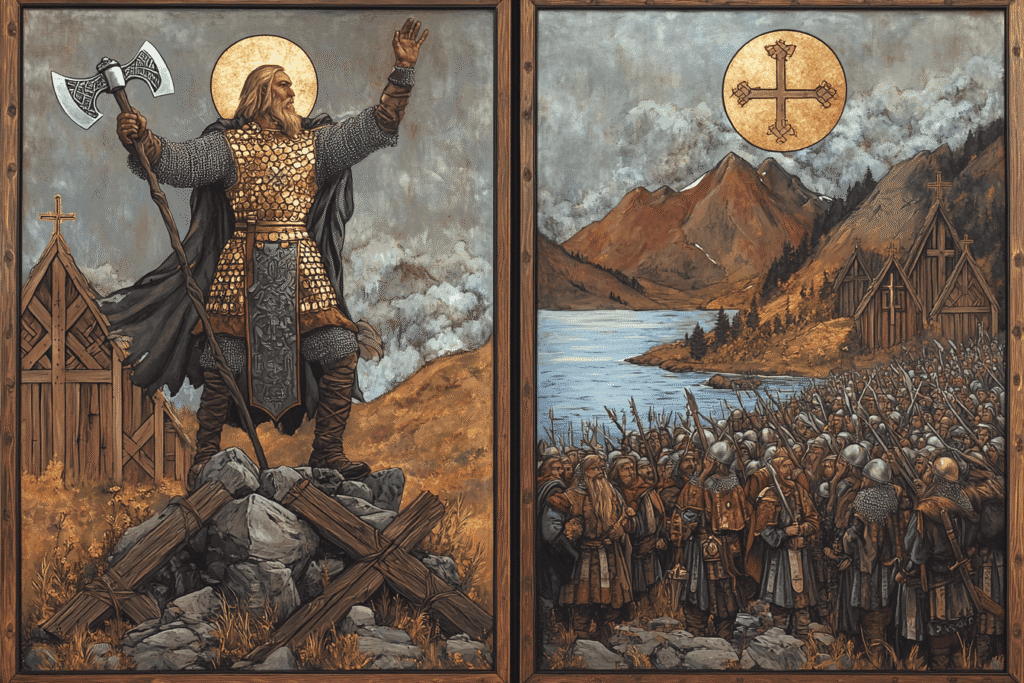

Olaf’s most profound legacy lies in the Christianization of Norway. His efforts ensured that Christianity, not paganism, would shape the nation’s future. After his death, the spread of Christianity accelerated, and pagan customs gradually faded. The laws of the land incorporated Christian values, and the Church of Norway became a central institution.

St. Olaf became a symbol of Norwegian independence and national pride, especially during periods of foreign domination or national revival. His image-often depicted with an axe, the symbol of Norway’s coat of arms-embodied the fusion of Viking strength and Christian virtue. His feast day, Olsok (July 29), remains a day of celebration in Norway.

Olaf’s shrine at Nidaros became one of the most important pilgrimage sites in medieval Europe, drawing visitors from across Scandinavia and beyond. Churches dedicated to St. Olaf sprang up throughout Norway, Sweden, Iceland, and even as far as Finland and Germany.

St. Olaf in England: The Viking Saint Across the Sea

Olaf’s influence was not confined to Scandinavia. The cult of St. Olaf found fertile ground in England, particularly among communities with Scandinavian roots. Several English churches were dedicated to him – often under the name St. Olave. Notably, St. Olave’s Church in York, mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1055, is considered the earliest known English church dedicated to Olaf.

The dedication of churches to St. Olaf in England reflects the intermingling of Viking and Anglo-Saxon cultures during a period of intense conflict and migration. For Scandinavian immigrants, Olaf was both a spiritual protector and a link to their ancestral homeland.

A Saint for East and West

Unusually, St. Olaf was venerated by both the Western and Eastern churches. He became the patron saint of the Varangians, the elite Scandinavian bodyguards of the Byzantine emperors. The chapel of the Varangians in Constantinople was dedicated to him, making Olaf the last Western saint accepted by the Eastern Orthodox Church before the Great Schism.