Olaf Cuarán, also known as Amlaíb mac Sitric or Olaf Sihtricson, was a formidable figure in the tumultuous world of 10th-century Britain and Ireland. His life, spanning roughly from 920 to 981, was marked by dramatic shifts in fortune, fierce battles, political marriages, and a legacy that would echo through the centuries as the last great Norse-Gael king to shape the destiny of both Dublin and York. His story is one of ambition, resilience, and the relentless tides of history that swept across the Irish Sea.

Origins and Early Life

Olaf Cuarán was born into the powerful Uí Ímair dynasty, a Norse-Gaelic royal house that dominated the Irish Sea region for generations. His father, Sitric Cáech, was King of Northumbria (in England) and Dublin, and his lineage traced back to the legendary Ivar the Boneless. Olaf’s early years were spent in the shadow of these great Viking lords, absorbing the complex interplay of Norse and Gaelic cultures that defined his world.

Following his father’s death in 927, Olaf’s fortunes took a dramatic turn. The English king Æthelstan seized Deira (part of Northumbria), forcing Olaf to seek refuge in Scotland then Ireland. During these formative years, he participated in the fateful Battle of Brunanburh in 937, fighting alongside a coalition of Norse, Scots, and Britons against Athelstan’s English army.

The Battle of Brunaburh

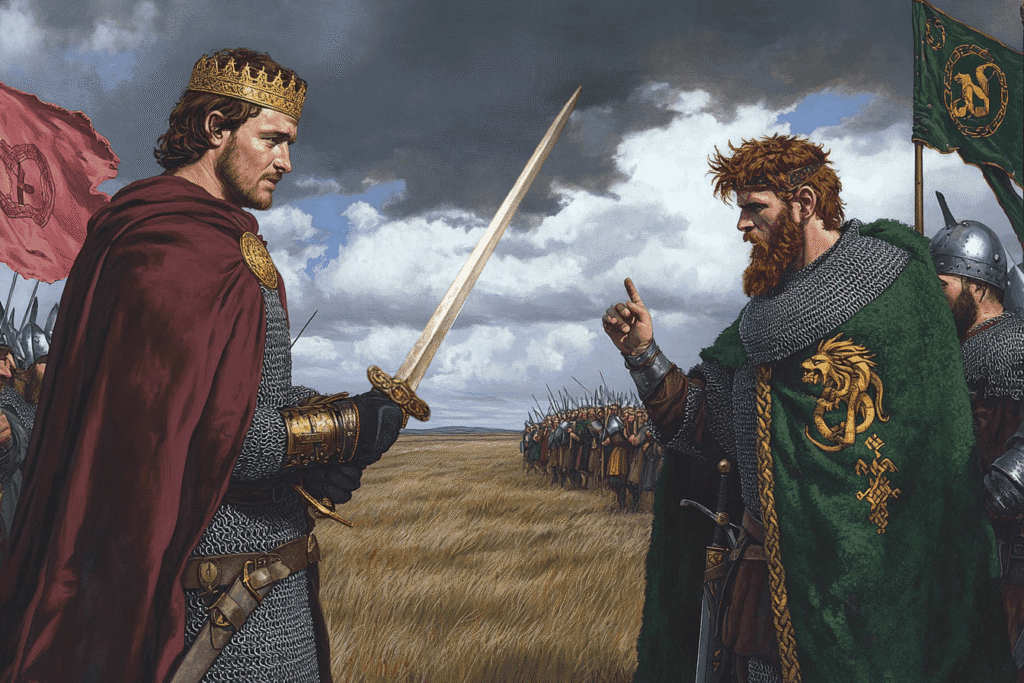

On a chill autumn morning in 937, the fate of Britain hung in the balance as two massive armies faced each other at Brunanburh. The English king, Æthelstan, stood at the head of his forces, flanked by his brother Edmund. Arrayed against them was a formidable coalition: Olaf Guthfrithson, Hiberno-Norse King of Dublin (Olaf Cuarán’s cousin), Constantine II of Scotland, and Owain of celtic Strathclyde, each commanding warriors from across the British Isles and beyond.

Amid the chaos of battle, Æthelstan’s leadership proved decisive. He split his army, taking the left wing himself to face Olaf by the river, while Edmund commanded the right against the Scots. The fighting was brutal and close; the shield wall – a test of endurance and nerve – began to buckle under the relentless assault. As fatigue and losses mounted, a breach opened in the invaders’ line. The Mercians surged through, and the shield wall collapsed. What followed was a rout: the English pressed their advantage, cutting down fleeing foes as the sun dipped toward the horizon.

The carnage was immense. Five kings and seven Viking earls fell with Olaf’s army; Constantine lost his son and many kin. The English, too, paid dearly – two of Æthelstan’s cousins were among the dead, alongside bishops and countless lesser men.

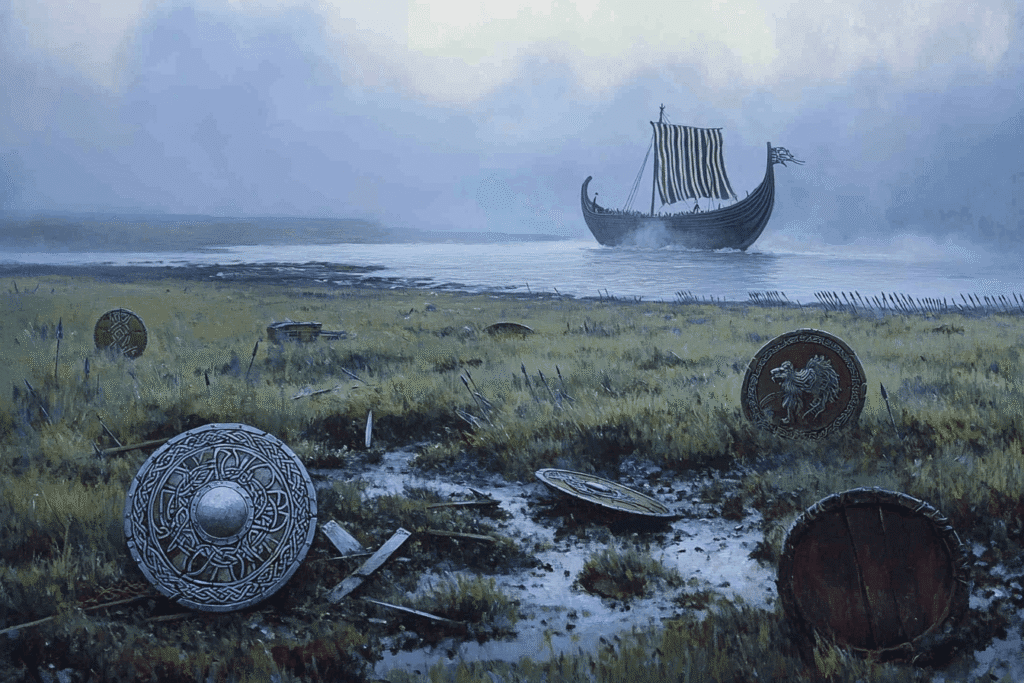

As night fell, the remnants of the coalition fled. Olaf escaped by ship back to Dublin, his army shattered, his cousin with him. Constantine made for Scotland, his ambitions in ruins. The field was littered with the bodies of the fallen – Norse, Scot, Briton, and Saxon alike.

Æthelstan and Edmund returned south in triumph, their victory securing Æthelstan’s rule and forging the idea of a united English kingdom; correspondingly, it was a significant setback for the Norse-Gaelic cause, but it did not extinguish Olaf’s ambitions.

The Struggle for York

The death of Athelstan in 939 created a power vacuum in Northumbria. Olaf Guthfrithson, invaded and forced Athelstan’s successor, Edmund, to cede Deira. Upon Olaf Guthfrithson’s death in 942, Olaf Cuarán seized the opportunity to claim both York and Dublin, seeking to restore his family’s dominance over the region.

Olaf’s rule in York was shared with his cousin Ragnall, and together they launched raids deep into English territory, sacking towns such as Tamworth and Northampton in the English midlands. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Olaf destroyed Tamworth, inflicted heavy casualties, and seized considerable booty, though these victories were short-lived.

In 943, Olaf was baptized in England, with King Edmund standing as his sponsor – a move likely motivated more by political expediency than genuine religious conviction. Despite this, the Northumbrians soon expelled him, replacing him with Ragnall. Olaf’s fortunes in York would wax and wane over the next decade: he briefly regained the throne in 949, only to be ousted again in 952 by the formidable Erik Bloodaxe.

King of Dublin: Power and Turmoil

After his final expulsion from York, Olaf gave up on trying to hold land in England and turned his attention to Dublin, the Norse stronghold on the Irish coast. Dublin had been rebuilt after its destruction by the Irish, and Olaf, ever the opportunist, reclaimed his position as king. His reign in Dublin was anything but peaceful. The city was a nexus of Norse and Irish interests, and Olaf found himself embroiled in a constant struggle for supremacy.

Olaf’s rule was challenged by rival kinsmen – his cousins Blacaire and Ragnall – and by the native Irish kings. The annals record a series of battles, alliances, betrayals, and shifting loyalties. In 945, Olaf rebuilt Dublin and consolidated his power, but the years that followed saw repeated conflicts with Irish rulers such as Congalach, King of Brega, and Domhnall O’Neill, High King of Ireland.

In 956, Olaf defeated and killed Congalach, a significant victory that temporarily strengthened his position. He continued to wage war against his rivals, sacking the monastic community of Kildare in 964 and plundering Kells in 970, often in alliance with the Leinster Irish. Yet, these victories were tempered by defeats, such as his loss at Inistioge to the men of Ossory in 964.

Diplomacy, Marriage, and Legacy

Olaf Cuarán was as adept at diplomacy as he was at war. He forged alliances through marriage, marrying at least three times. His wives included a daughter of Constantine III of Scotland, Gormflaith (a powerful Leinster princess who would later marry Brian Boru), and Dúnlaith ingen Muirchertach of Ailech. These unions produced children who would play important roles in the politics of Ireland and the Norse world. His son Sigtrygg Silkbeard, by Gormflaith, would become one of the most renowned kings of Dublin.

Olaf also engaged with the cultural life of his time. He was a patron of poets and skalds, commissioning works from both Irish and Scandinavian bards. One famous poet, Cináed ua hArtacáin, was rewarded by Olaf with a well-bred horse for his verses. Despite his reputation as a ruthless pillager of churches, Olaf sought to legitimize his rule by adopting the customs and patronage networks of the Irish kings.

The Battle of Tara and Olaf’s Final Days

The twilight of Olaf’s reign was marked by one of the most decisive battles in Irish history: the Battle of Tara in 980. Facing the rising power of Mael Sechnaill mac Domnaill, King of Meath, supported by forces from Ulster and Leinster, Olaf led his Dublin forces into battle, supported by troops from the Hebrides, commanded by his son Ragnall.

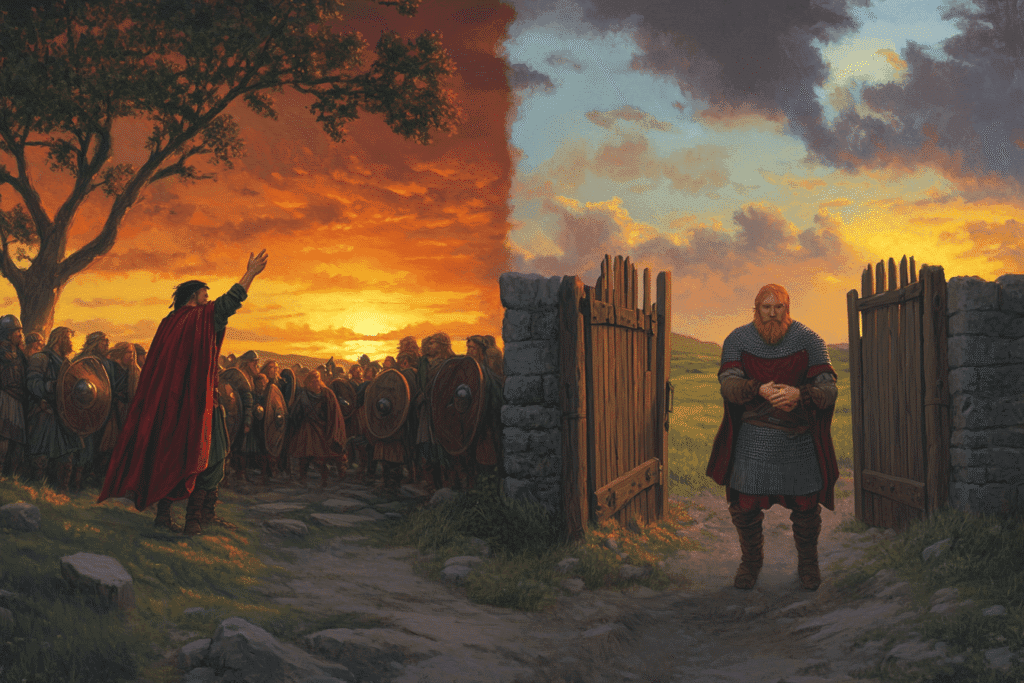

For hours the Norse shield wall held, but the Irish pressed relentlessly. The tide turned when the Irish main force surged forward, breaking the Viking formation and sending panic rippling through their ranks. The rout was swift and brutal. Norse warriors fled toward Dublin, many cut down as they ran, others surrendering in desperation. The Viking army was destroyed; the survivors scattered.

Máel Sechnaill’s victory did not end with the battlefield. He marched on Dublin, besieging the city for three days. When it fell, he freed over 2,000 Irish slaves and forced the Norse to surrender their claims to Irish land and tribute. This act, both political and humane, resonated across Ireland, undermining the Norse economy and cementing Máel Sechnaill’s reputation as a liberator.

Broken-hearted and defeated, Olaf retired to the monastic sanctuary of Iona, where he died in 981. His death marked the end of an era: Dublin’s role shifted from a Viking kingdom to a major trading center under Irish suzerainty.

Olaf Cuarán’s Enduring Legacy

Olaf Cuarán’s life was a microcosm of the Viking Age’s final century in the British Isles. He was a warrior-king, a shrewd politician, and a cultural bridge between Norse and Gaelic worlds. His descendants, notably Sigtrygg Silkbeard, continued to rule in Dublin and the Isle of Man, and the memory of Olaf Cuarán lived on in both Irish and Norse tradition. He was even immortalized in medieval romance as the prototype for Havelok the Dane.

In the end, Olaf Cuarán was both a product and a shaper of his times – a king whose life embodied the turbulence, ambition, and cultural fusion of the Viking world at the edge of its twilight.