The “Rule of the Harlots,” also known as the Saeculum obscurum or Pornocracy, marks one of the most infamous and controversial periods in the history of the papacy. Spanning roughly sixty years from 904 CE, this era was characterized by the profound influence of a powerful Roman aristocratic family – the Theophylacti – over the papal throne, and by accounts of rampant corruption, intrigue, and scandal at the heart of Christendom.

Origins: Seeds of Chaos

The roots of the Rule of the Harlots can be traced to the political and social upheaval that followed the death of Pope Formosus in 896. The late ninth and early tenth centuries were marked by instability, with seven or eight papal elections occurring in as many years. The papacy, once a stabilizing force, became a pawn in the power struggles between Roman nobility and external rulers.

The Frankish Carolingian dynasty’s decline and the fragmentation of imperial authority left Rome vulnerable to the ambitions of its aristocratic families. The Theophylacti, leveraging their wealth and connections, rose to dominate the city and, by extension, the papal office. Their ascent set the stage for a period in which the papacy was less a spiritual institution and more a prize to be won and wielded for secular gain.

The Theophylacti and the Rise of Marozia

At the center of this drama stood Theophylact I, Count of Tusculum, and his wife Theodora, whose influence over the papacy was legendary. Their daughter, Marozia, would become the most notorious figure of the era. Chroniclers, especially Bishop Liutprand of Cremona, painted Marozia and her mother as the true rulers of Rome, manipulating popes and orchestrating their rise and fall.

Marozia’s power was not merely behind the scenes. She held the titles of senatrix and patricia of Rome, and her marriages and liaisons linked her to a succession of popes and noblemen. Her ability to install and depose popes at will led to the widespread belief that the papacy was under the control of “harlots” – a characterization that, while vivid, is now recognized as being colored by the misogyny and political biases of the time.

The Papacy Under Siege

The Rule of the Harlots began in earnest with the installation of Pope Sergius III in 904, a figure closely associated with the Theophylacti. Sergius’s papacy set a precedent for the era: popes were often chosen for their loyalty to the ruling family rather than their spiritual or moral qualifications. Sergius ascended to the papal throne through a violent coup, reportedly orchestrating the murders of his predecessors, Leo V and Antipope Christopher, to secure his position.

Sergius’s reign was characterized by rampant nepotism and the promotion of his own family and political allies to positions of power within the church. His personal life was equally controversial. Chroniclers, especially the hostile Liutprand of Cremona, alleged that Sergius had an affair with Marozia. This liaison supposedly produced an illegitimate son, who would later become Pope John XI, certainly the persistent rumors reinforced the perception of a corrupt and decadent papacy.

The Cadaver Synod and Ecclesiastical Turmoil

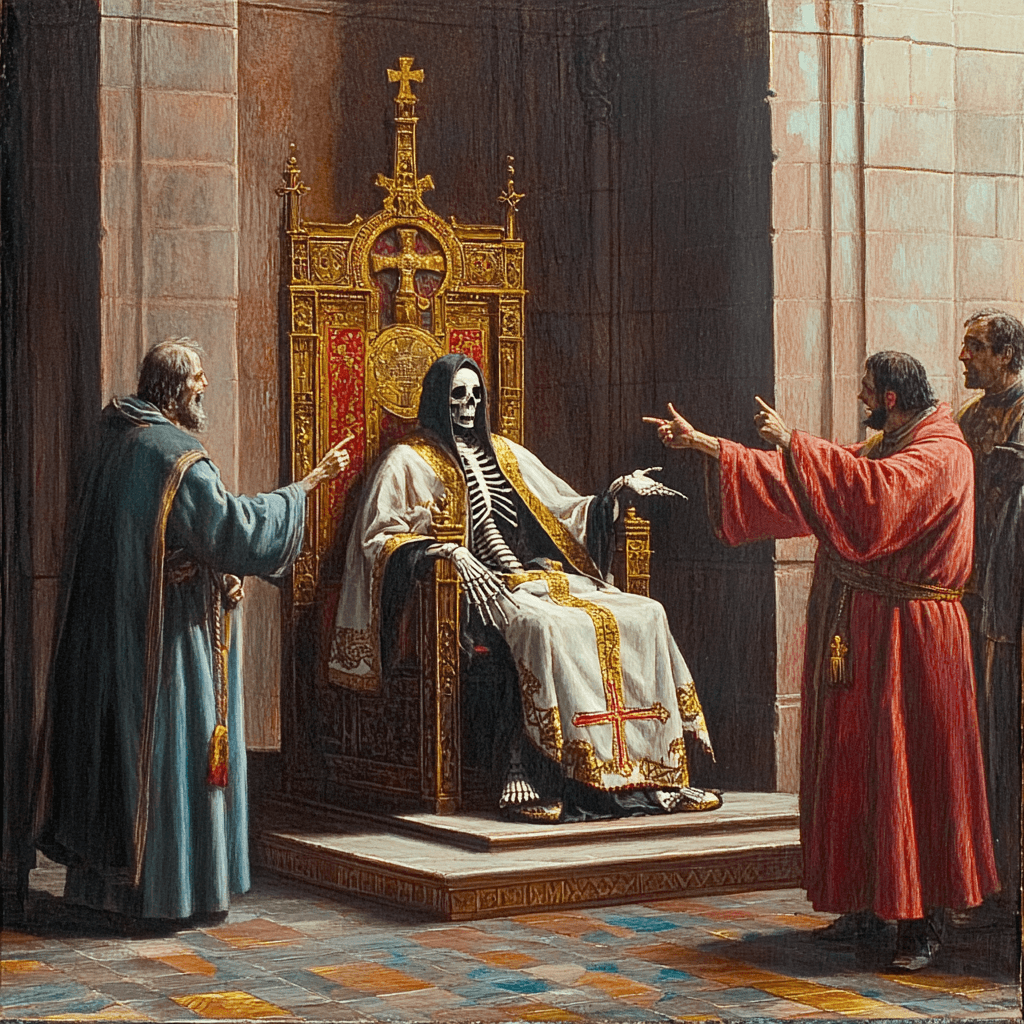

Sergius III’s involvement in the aftermath of the Cadaver Synod – where the corpse of Pope Formosus was disinterred, clad in papal vestments, and seated on a throne to face charges from Pope Stephen VI – added to his notoriety. As a staunch supporter of Stephen VI, he convened a synod that reaffirmed the acts of the Cadaver Synod, once again invalidating all ordinations performed by Pope Formosus. This decision, reportedly secured through bribery, threats, and violence, caused widespread unrest within the church. Bishops outside Rome largely ignored Sergius’s decrees, and the controversy over Formosus’s legacy continued to fester.

The reign of Sergius III is widely regarded as a low point in papal history. Contemporary and later chroniclers described his pontificate as “dismal and disgraceful,” marked by murder, corruption, and moral bankruptcy. His willingness to serve as a tool of secular powers, his alleged personal scandals, and his ruthless suppression of rivals left a legacy that overshadowed any positive contributions he may have made.

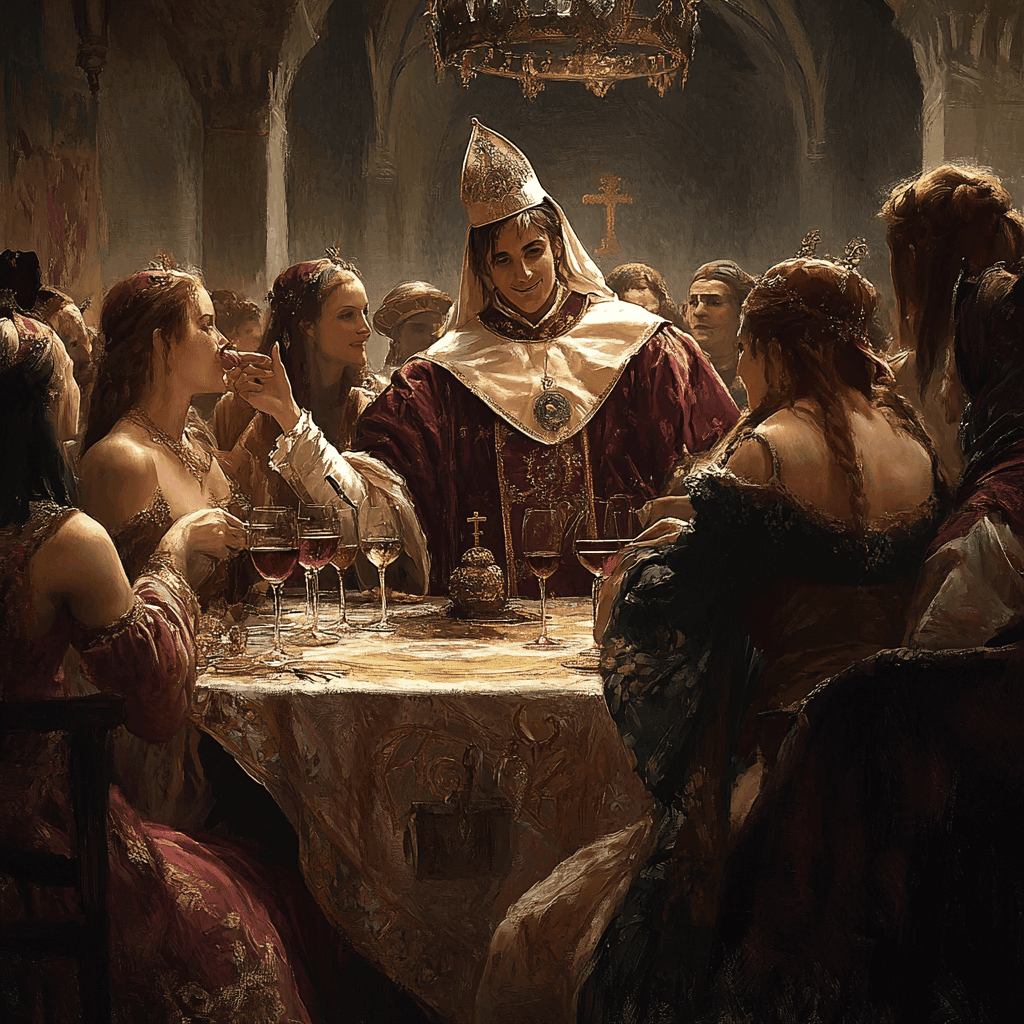

The influence of the Theophylacti was not limited to political maneuvering. Contemporary sources accused the papal court of moral decadence, with tales of simony, nepotism, and sexual scandal abounding. The papal palace, it was said, became “an abode of riot and debauchery,” and the Church’s spiritual authority was severely undermined.

Pope John X1

Marozia’s grip on Rome was so tight that in 931 she orchestrated the election of her son John’s election as pope at the age of just 21, despite his lack of experience or qualifications. He was little more than a pawn, raised to the papacy to serve his mother’s political interests.

Marozia herself was infamous for her multiple marriages and alleged affairs. She was accused of orchestrating the deposition and death of Pope John X, clearing the way for her son’s rise to power. Her marriage to Hugh of Italy, a move intended to strengthen her political position, backfired spectacularly. The union was so unpopular and her rule so resented that a rebellion led by her own son, Alberic II, resulted in her imprisonment and the exile of her husband.

After Marozia’s fall from power in 932, John XI’s situation grew even more dire. His half-brother Alberic II seized control of Rome and confined John to the Lateran Palace, effectively making him a prisoner for the remainder of his life. Stripped of all secular and even most ecclesiastical authority, John was reduced to performing only the most basic spiritual duties, while Alberic II ruled the city and the Church with an iron hand.

John XI’s pontificate was marked by his utter lack of autonomy. Even important ecclesiastical decisions, such as the granting of the pallium to the Archbishop of Reims and the confirmation of the Patriarch of Constantinople, were made at the insistence of Alberic II, not the pope himself. John’s reign, therefore, stands as a symbol of the papacy’s subjugation to secular power during this period.

John XI died in December 935, still a virtual prisoner. His brief, ignominious reign is remembered as one of the lowest points in papal history – a time when the spiritual leader of the Catholic Church was a mere puppet of his family’s ambitions, and when the papacy itself was widely seen as corrupt and scandal-ridden.

Yet, even in this dark chapter, some seeds of reform were sown. John XI granted privileges to the Congregation of Cluny, which would later become a driving force for renewal and moral reform in the Church. His reign, therefore, marks both the nadir of papal authority and the beginning of the long road to recovery.

Pope John XII

Marozia’s grandson became the next pope – John XII – and his reign quickly became synonymous with excess and depravity. Contemporary chroniclers and later historians alike accused him of transforming the Lateran Palace, the papal residence, into a den of vice – a “brothel” where mistresses, concubines, and women of ill repute mingled with the clergy. His sexual exploits were legendary, reportedly involving noblewomen, widows, his father’s former concubine, and even his own niece. The chronicler Liutprand of Cremona, admittedly an ally of John’s political rival Otto I, painted a lurid picture of the pope’s court, describing orgies, gambling, and drunken banquets where John XII toasted the devil and invoked pagan gods.

His disregard for ecclesiastical norms did not stop at personal vice. John XII was accused of simony – selling church offices for money and political support-undermining the Church’s spiritual authority. He reportedly celebrated Mass without taking communion, ordained clergy in stables, and neglected even the most basic religious gestures, such as making the sign of the cross. Churches fell into disrepair, and the sacred was routinely profaned.

The list of his alleged crimes grew to include violence and murder. He was said to have ordered the blinding of his confessor, castrated and killed a cardinal, and set fire to priests’ houses. These acts of brutality, combined with his licentiousness, made John XII’s papacy a byword for corruption and sacrilege even in an age not unaccustomed to clerical vice.

Political Intrigue and the Holy Roman Empire

Despite his personal failings, John XII was not without political cunning. Early in his papacy, he sought to assert papal authority by leading military campaigns to reclaim lost papal territories, though these efforts ended in failure and left him vulnerable to his enemies. Facing threats from Berengar II, King of Italy, John turned to Otto I, King of Germany, for military assistance. In 962, in a move that would shape European history, John crowned Otto as Holy Roman Emperor, reviving the imperial title first bestowed on Charlemagne.

This alliance, however, was short-lived. John XII soon regretted granting Otto so much power and began plotting with Otto’s enemies, including Berengar’s son and foreign powers like the Magyars and Byzantines. Otto, discovering the betrayal, marched on Rome, deposed John, and installed Leo VIII as pope. John fled with the papal treasury but soon returned with his own supporters, briefly reclaiming the papacy and forcing Leo VIII into exile.

However, John XII’s return to power was fleeting. His enemies were legion, and his reputation was irreparably tarnished. In 963, the Synod of Rome, convened by Otto, formally charged John with a litany of crimes: perjury, sacrilege, murder, adultery, incest, and desecration of holy spaces. The charges were so severe that Otto declared, “You are accused of such heinous misdeeds that our faces would blush even if you were an ordinary actor. It would take a whole day to list them all here”.

John’s final days were as ignominious as his reign. According to legend, he died at age 27, either of a stroke while in bed with a married woman or, in a more dramatic version, after being thrown from a window by the enraged husband. He was buried in the Lateran Palace, the site of so many of his excesses.

Legacy and Reappraisal

The Rule of the Harlots remains a cautionary tale in the history of the Church, it was a period of extraordinary turbulence and scandal in the history of the papacy. While the lurid tales of debauchery and corruption have been amplified by centuries of polemic and propaganda, the underlying reality was one of profound institutional weakness and the struggle for power in a fractured world. The era’s legacy endures, not only as a warning of the perils of corruption but also as a testament to the resilience of the papacy, which would eventually emerge from its darkest hour to reclaim its spiritual and moral authority