In the early 9th century, the Balkan Peninsula was a cauldron of rivalry and ambition. The Byzantine Empire, heir to Rome’s eastern legacy, sought to reassert its dominance over its northern neighbors, especially the First Bulgarian Empire. The Battle of Pliska, fought on 26 July 811 AD, became a defining moment in this struggle – a catastrophic defeat for Byzantium and a triumph for Bulgarian resilience under the leadership of Khan Krum.

Background: Byzantine–Bulgarian Rivalry

The roots of the conflict trace back to the late 7th century, when the Bulgars, a Turkic people from the Pontic Steppe, migrated toward the Danube region. They defeated Byzantine forces and, by subduing local Slavic communities, established a powerful state that blended nomadic warrior traditions with settled agricultural society. The Bulgars’ rise was marked by their victory at the Battle of Ongal in 680, which forced the Byzantine Empire to recognize Bulgaria as a legitimate state – an unprecedented humiliation for Constantinople.

Relations between the two powers oscillated between uneasy truces and open warfare. By the early 9th century, the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros I (r. 802–811) was determined to reclaim lost territory and reassert imperial authority over the Balkans. His ambitions set the stage for a dramatic confrontation.

The Road to Pliska

In 807, Nikephoros launched his first campaign against the Bulgars, but internal conspiracies in Constantinople forced him to abort the effort. The Bulgars seized the initiative: Khan Krum counterattacked, capturing the strategic city of Serdica (modern Sofia) in 809. Determined to crush the Bulgarian threat, Nikephoros assembled a massive army in 811, drawing troops from across the empire and including many irregulars eager for plunder.

The Byzantines marched north through the Balkan Mountains, their goal clear: to capture Pliska, the Bulgarian capital. The approach of this formidable force caused panic among the Bulgarian populace, who fled into the hills and mountains. Krum, recognizing the danger, withdrew his main forces into the mountains, leaving a token force to defend the capital.

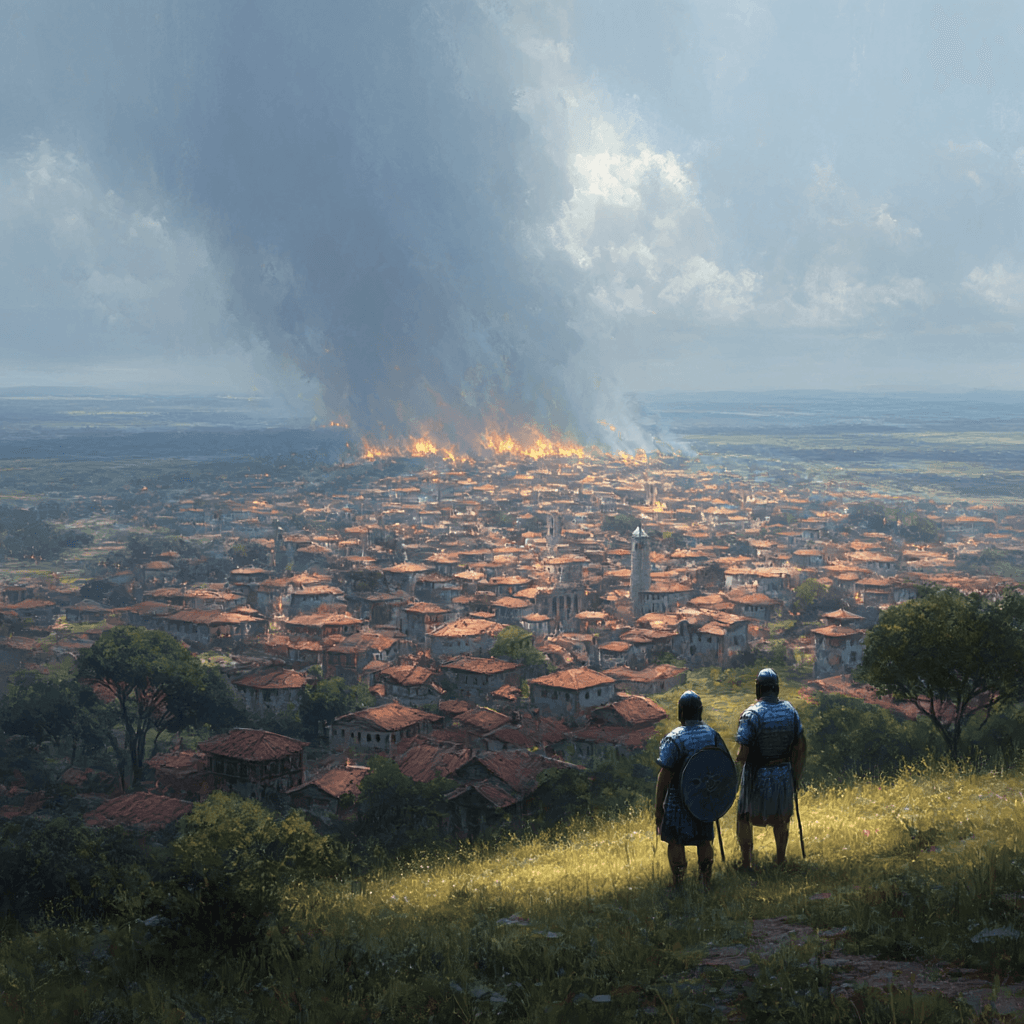

The Fall and Sack of Pliska

On 23 July 811, the Byzantines reached Pliska. The city was virtually undefended, and Nikephoros’s troops quickly captured it. What followed was a scene of destruction: the Byzantines looted and burned Pliska, seizing the khan’s treasury and devastating the capital. The emperor and his high-ranking officials, confident of victory, celebrated their success. Many believed the campaign was over and that the Bulgars had been decisively defeated.

However, while the Byzantines indulged in plunder, Krum was far from finished. He mobilized his people, including women and Avar mercenaries, and set about preparing a devastating trap in the mountain passes that the Byzantines would need to cross on their return journey.

The Trap in the Vărbitsa Pass

As the Byzantine army, burdened with loot and complacent after their “victory,” began its retreat, Krum’s forces blocked the passes in the Balkan Mountains – most notably the Vărbitsa Pass. The Bulgars constructed thick wooden barricades and fortified the heights overlooking the narrow valley, creating a deadly killing ground.

Nikephoros, ignoring warnings from his scouts, led his army into the pass on 25 July. When the Byzantines realized the road was blocked, they attempted to burn the wooden walls, but the Bulgars had prepared a moat behind the barricade, trapping the invaders in a confined space. Unable to maneuver, the emperor ordered his troops to make camp, despite the pleas of his generals to break out immediately.

That night, the Bulgars tightened their encirclement. At dawn, they launched a surprise attack, descending from the heights and charging into the Byzantine camp. The Byzantines, caught off guard and unable to form effective battle lines, were slaughtered en masse. Some were cut down by sword, others drowned in the muddy river while fleeing, and still others perished in the fires they themselves had started to burn the barricades. The battle was a complete disaster for the Byzantines: almost the entire army was annihilated, and Emperor Nikephoros I was killed – the first Byzantine emperor to die in battle since Valens at Adrianople in 378.

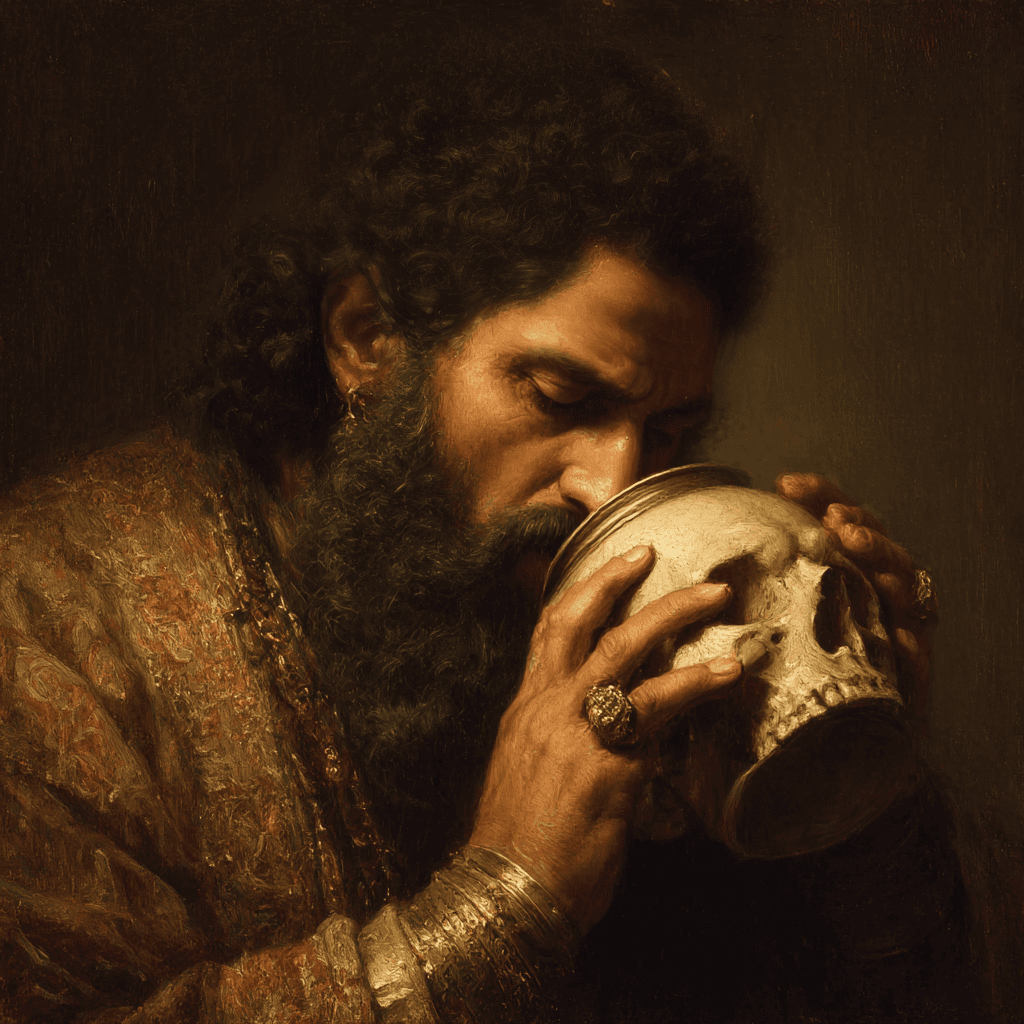

The Skull Cup: Symbol of Triumph and Defeat

The aftermath of the battle was marked by one of the most infamous acts in medieval Balkan history. According to contemporary accounts, Khan Krum ordered the head of Nikephoros to be displayed on a spike. He then had the emperor’s skull lined with silver and used it as a drinking cup – a macabre symbol of victory and a stark warning to future enemies. This act, while shocking, was rooted in steppe tradition and served to cement Krum’s reputation as a fearsome and uncompromising leader.

Consequences and Legacy

The Battle of Pliska was one of the worst defeats in Byzantine history. The loss of an emperor and the near-total destruction of a massive army sent shockwaves through the empire. The psychological impact was profound: for more than 150 years, Byzantine rulers were reluctant to send large armies north of the Balkans, allowing the Bulgarians to expand their influence and territory to the west and south.

For Bulgaria, the victory was a defining moment. Khan Krum’s leadership and the mobilization of the entire population – including women and mercenaries – demonstrated the resilience and unity of the young state. The victory at Pliska solidified the First Bulgarian Empire’s position as a major power in the region, capable of challenging the Byzantine Empire on equal terms.

Broader Historical Significance

The Battle of Pliska is significant not only for its immediate military and political consequences but also for its role in shaping the cultural and ethnic identity of the Balkans. The fusion of Bulgar and Slavic traditions, combined with the adoption of Roman bureaucratic practices, created a unique and enduring political entity. The battle also highlighted the importance of terrain and tactics in medieval warfare: the Bulgars’ use of ambush and fortification in the mountain passes proved decisive against a numerically superior but overconfident foe.

The defeat at Pliska forced the Byzantine Empire to reconsider its strategy in the Balkans, leading to a period of relative peace and consolidation. However, the rivalry between Byzantium and Bulgaria would continue for centuries, with both empires shaping the destiny of southeastern Europe.