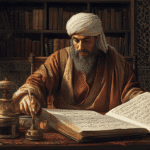

In the Candlelit Scriptorium

Geoffrey of Monmouth, a clever cleric with an eye for legend and a taste for literary mischief, was born around 1095. He is believed to have served as a canon at St. George’s College, rubbing elbows with nobles and theologians, an observer at the swirl of ideas, politics, and myth that colored Norman-English life.

There, by flickering candlelight, he began composing one of the wildest literary rides of the Middle Ages: the Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain). With a sharpened quill, Geoffrey set out to tell the story not only of his people but of a fantastical Britain that never quite was and yet would never again be forgotten.

The Book That Changed British Mythology

Historia Regum Britanniae is a sweeping epic that purports to chronicle some 2,000 years of British history, from the ancient days of Brutus the Trojan – a hero supposedly descended from Aeneas – down to the last of the Britons before the Anglo-Saxons claimed the land. While much of his narrative would make true historians grimace, Geoffrey’s wild invention would prove irresistible to generations of readers eager to hear stories of heroism, betrayal, prophecy, and magic.

This was a quest not for historical accuracy, but for grandeur. Kings rise and fall. Giants walk the land. Roman emperors invade, only to be bested by bold Britons. The tale is at once a chronicle and a romance, an origin myth and a work of proto-nationalism. In the Historia, Geoffrey retells – often invents – episodes that would shape British legend: King Leir and his three faithless daughters (the inspiration for Shakespeare’s King Lear), Merlin the enchanter, the noble Arthur, the sword-wielding Uther Pendragon, and more.

A Feast of Fantastical Origins

Geoffrey begins his history not in the muddy heartlands of the real Britain, but with Brutus, great-grandson of Aeneas of Troy, striding onto Albion’s shores. The British nation, he says, is forged at Troy’s embers – not a downtrodden backwater, but a land of heroic descent! Brutus banishes giants, founds cities, and foreshadows civilizations to come. Geoffrey describes temples to Diana and sacrifices to Jupiter, conjuring a Britain not just ancient but mythic, peopled with echoes of Rome and Greece.

With each king, Geoffrey’s narrative grows ever taller:

- Bladud, who founds the city of Bath by harnessing its mystical hot springs, and learns the dangerous art of flying (with predictably tragic results).

- Leir of Leicester, whose heartbreaking tale of filial betrayal and blindness prefigures Shakespeare’s tragedy.

- Cymbeline, whose reign brings a golden age before the shadow of Rome falls.

The kings multiply. Some become legendary for justice and wisdom; others grievously fall, undone by hubris, jealousy, or fate’s cruel hand.

Romans, Saxons, and Legendary Resistance

Geoffrey’s Britons seldom go quietly into the night. When Julius Caesar arrives to conquer, he is met by Cassivellaunus, a king so cunning he outsmarts Rome’s legions. Although the Britons eventually submit (with a suitable flourish), Geoffrey insists their resistance was fierce and glorious.

Centuries tumble past in a riot of names, battles, and betrayals. After the Romans tire of war and retreat, Geoffrey’s Britons are beset by Picts, Scots, and Danes. Seeking allies, the desperate Vortigern calls in the Saxons – only for these mercenaries to seize the land for themselves. Chaos breeds new heroes. Into the storm steps Merlin, transformed from Welsh wildman Myrddin Wyllt into the immortal wizard who weaves prophecy into politics and helps guide kings.

Geoffrey’s Merlin is a seer, a builder, and a master of riddle – his prophecies, rendered in thunderous verse, foretell both glorious victories and apocalyptic ruin. The wizard becomes a fixture in tales of Vortigern, Aurelius Ambrosius, and Uther Pendragon, whose union (with Merlin’s help) famously gives rise to Arthur.

The Age of Arthur

If Geoffrey had simply stopped with Trojan founders and battling Britons, his book might have faded. But with Arthur, he built an edifice that European literature would never escape. Arthur steps forth as king and conqueror – no mere regional warlord, but an emperor whose banner flies from Ireland to Norway, Iceland to Burgundy. Arthur’s court becomes a place of chivalry and high adventure, a golden age amid darkness.

There are echoes here of Welsh poetry, of earlier Celtic stories – yet Geoffrey weaves them into a tapestry both grander and more dramatic than before. Sir Kay and Sir Bedivere fight at Arthur’s side. Mordred, the traitor, brings doom. Camelot shimmers on the horizon, and the lady in the lake offers Arthur a sword.

Geoffrey tells of great battles, magical beasts, the taking of Rome (an audacious, utterly invented feat), and finally Arthur’s fall at Camlann and his journey to Avalon – a departure that would, centuries later, fuel the hope of the “once and future king.”

A Book of Its Time

Why did Geoffrey write such marvels? The 1130s were a time of turmoil in the British Isles. The Norman conquest was still reshaping cultures, languages, and landowning patterns; kings and nobles vied for legitimacy. Geoffrey’s work, written in Latin but championing a British past, offered both a tool and a consolation: a story that tied new Norman rulers to ancient, noble roots and soothed the anxieties of a conquered people by claiming the island for myth and legend alike.

Geoffrey dedicated his book to powerful men – Robert, Earl of Gloucester; Bishop Alexander of Lincoln; and Stephen, King of England – all eager for a grand narrative that could flatter, inspire, or distract. His sources? Geoffrey famously claimed to be translating a “very old book in the British tongue” brought from Brittany by Walter, archdeacon of Oxford. Modern scholars, and many of Geoffrey’s own contemporaries, quickly saw this “source” as invention or wishful thinking.

Yet Geoffrey’s genius was not in discovery, but in synthesis. He plundered Welsh legends, borrowed freely from Bede, Gildas, and Nennius, then spun his own golden thread through the weave.

Reception, Influence, and Legacy

For centuries, Geoffrey’s opus was treated as gospel truth. Chroniclers, poets, and royalty all embraced his tales; for many, “King Arthur” and the Trojan Brutus were as real as William the Conqueror. The Historia inspired later writers across Europe, from the French romances to Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. Even Shakespeare drew from its riches.

Doubters sharpened their pens over time. The Italian historian Polydore Vergil, in the sixteenth century, famously declared Geoffrey’s stories fables. Yet the damage, and the magic, were done. Geoffrey’s version of history would outlast mere facts; his legacy remains in every retelling of the Arthurian cycle, every reference to Lear’s tragedy, every poetic vision of Avalon’s green hills.

An Entertaining Tapestry: Style and Substance

Geoffrey’s prose style is robust, dramatic, and colored with the rhetorical flourishes of a born storyteller. His kings declaim speeches in the style of Roman senators; his wizards cast spells in thunderous verse. He never met an awkward genealogical connection he could not resolve with a marriage, a prophecy, or the appearance of giants.

His work is sheer fun – a cross between Game of Thrones and mythic epic, brimming with duels, councils, sieges, and magical intrigues. Even his “facts” often hint at a wink and a nudge: why should history be dull when it can sparkle?

The Truth Behind the Legend

Modern readers are quick to dismiss Geoffrey as a fabulist, but his real achievement is subtler. Historia Regum Britanniae is a mirror held up not to the past, but to Geoffrey’s present and future – a tool for legitimizing power, for comforting the vanquished, for building the English imagination anew. His stories tell us as much about 12th-century concerns as they do about pseudo-historical kings, revealing the way myth and history intertwine.

Above all, Geoffrey reminds us that history is, at its heart, a story – and sometimes the most enduring ones are those laced with wonder, wit, and daring invention.

Epilogue: Geoffrey’s Final Days

Geoffrey, clever and ambitious, did not end his days simply a copyist or a dreamer. He rose to become the Bishop of St. Asaph, witnessed major charters, and likely enjoyed the fame and controversy his book brought. When he died in 1155, his Historia was already on its way to becoming a cornerstone of British myth. Subsequent ages would debate, parody, or denounce him, but no one would easily forget him.

So next time you linger over tales of Arthur, Merlin, or the wild kings who once ruled this “precious stone set in the silver sea,” remember the scribe from Monmouth. He taught the world how to make legend – out of little more than ink, imagination, and a hunger for greatness.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, with quill in hand, eternal as his words: chronicler, trickster, and architect of Britain’s grandest myths.