The closing years of the eighth century were a time of turbulence, transformation, and realignment across Europe. The once-mighty Roman Empire was long gone, its western half fractured into kingdoms and territories ruled by ambitious warlords or rising dynasties. It was in this fragile setting that Pope Leo III, head of the Roman Church, suffered a dramatic attack by enemies who sought to discredit and destroy him.

The Background: Rome in the Late Eighth Century

Rome in the late eighth century bore little resemblance to the imperial capital of antiquity. Its glory days as the center of the ancient world had ended centuries before, and the city was reduced to a shadow of its past magnificence. Once teeming with hundreds of thousands, Rome’s population had dwindled drastically. Ancient structures, crumbling from centuries without upkeep, were mined for stone. Nevertheless, Rome retained a prestige and sanctity far greater than its material wealth or military strength.

The Pope, successor of Saint Peter, stood at the head of the Western Church. However, the papal office was as much a political one as it was spiritual. While the Church had secured lands through the Donation of Pepin (granted by Pepin the Short, Charlemagne’s father), papal authority in Rome faced constant opposition from noble families within the city. Many Roman aristocrats, descendants of patrician families, resented the increasing involvement of Frankish kings in Italian affairs and jealously guarded their influence within the papal court.

Pope Leo III

Elected in December 795, Pope Leo III was not from Rome’s old aristocracy. His background made him suspect in the eyes of Rome’s noble elite, who favored papal candidates from their own ranks. Although Leo was pious and diligent, he lacked strong connections within the city to secure unquestioned loyalty.

Tensions soon erupted into open hostility. Allegations of corruption and personal misconduct, whether true or politically motivated, circulated widely. In societies where accusation was itself a weapon, enemies of the Pope understood the power of scandal to weaken papal legitimacy.

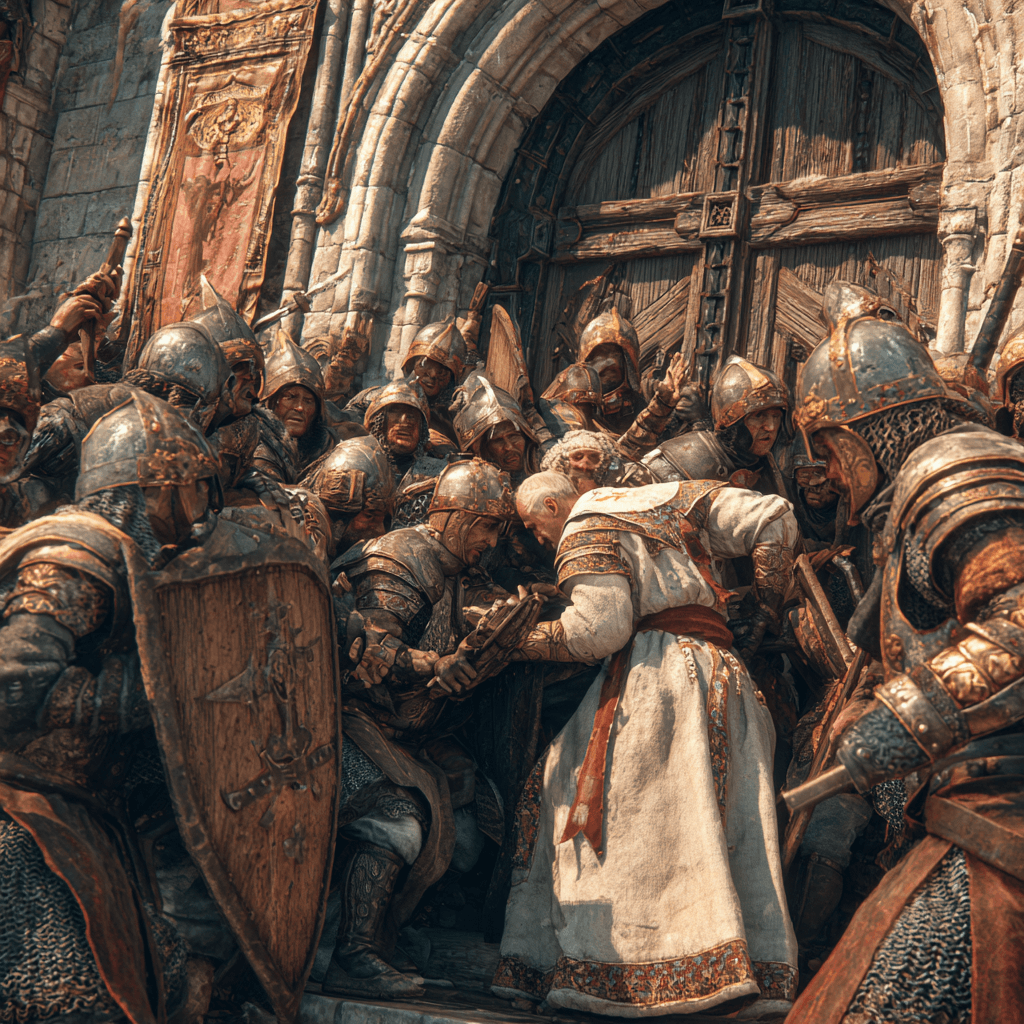

The Attack of April 799

On April 25, 799, the Feast of St. Mark, Pope Leo III took part in a public procession through the streets of Rome. At that moment, a band of armed men, made up of high-ranking Roman nobles opposed to his rule, suddenly surrounded and assaulted him.

According to later accounts, they attempted to blind him and cut out his tongue, an act intended not only to humiliate him but to disqualify him permanently from office, as a mutilated man was considered unfit to serve as Pope. Though severely beaten and left bloodied, Leo miraculously did not lose his sight or speech.

This shocking attack in broad daylight revealed just how vulnerable the papacy was. Rome’s noble families had, in effect, staged a violent coup attempt against the spiritual leader of Christendom.

Rescue and Escape

Leo’s loyal supporters managed to free him from his attackers. He was given refuge in the monastery of Saint Erasmus and later in the protection of Saxon soldiers loyal to Charlemagne who were stationed nearby. Realizing that he could not guarantee his safety in the city itself, Leo fled Rome entirely.

His destination was the court of Charlemagne, then residing in Paderborn in Saxony (modern-day Germany). The move was extraordinary: for the Pope himself to leave Italy and personally seek protection from a secular monarch underscored his desperate circumstances, but it also highlighted how reliant the Papacy had become on Frankish power.

Charlemagne Enters the Picture

Charlemagne (Charles the Great), king of the Franks since 768, was by 799 the most dominant ruler in Western Europe. Through campaigns in Saxony, Bavaria, and Italy, he had vastly expanded Frankish territory. He was a master of both war and governance, enforcing Christianization of conquered peoples and supporting the spread of learning and clerical reform.

For the Pope, Charlemagne was not simply a military ally, but a figure who represented stability in a turbulent world. Rome could no longer rely on Byzantine emperors for consistent protection. The Franks were the only power strong enough and close enough to intervene.

When Pope Leo arrived at Paderborn and threw himself at Charlemagne’s mercy, the king received him with reverence and hospitality. The presence of the Pope conferred spiritual legitimacy upon Charlemagne’s rule, while Charlemagne’s protection offered Leo a chance to reclaim his authority. Their relationship was one of mutual reinforcement.

Investigation and Return to Rome

Charlemagne understood the gravity of Leo’s situation. He did not immediately march an army to Rome, but he did escort Leo back, making clear to the Roman nobility that the Frankish king stood firmly by the papal cause. In November 799, Leo returned to his city under royal protection.

However, the accusations against him had not been silenced. His enemies charged him with perjury, misconduct, and immorality. A formal trial was demanded. Yet, as Pope, Leo could not be judged by any earthly power without undermining the spiritual supremacy of his office.

December 799: Oath of Purification

In order to put an end to the controversy, Charlemagne convened a council in Rome. Instead of facing a trial, Leo III took an oath of purification on December 23, 799, swearing before God and before Charlemagne that he was innocent of the charges. This symbolic resolution preserved both the dignity of the pope and the principle that only God could judge the apostolic successor of Peter.

Charlemagne, for his part, acted as a protector and arbiter – carefully balancing the independence of the papal office with the reality of Frankish power. The reconciliation between Leo and his Roman opponents smoothed the way for an even greater event to come.

The Road to the Imperial Coronation

The alliance between Leo III and Charlemagne reached its climax in the year 800. On Christmas Day, inside the majestic confines of St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Leo III placed a crown upon Charlemagne’s head, declaring him Emperor of the Romans (not quite the Holy Roman Emperor).

This act carried immense symbolic power. Though Charlemagne had already been the de facto ruler of the West, being crowned by the Pope linked his kingship with divine sanction and the legacy of ancient Rome. According to contemporary sources, Charlemagne claimed he had not anticipated this act, though many historians believe it was anticipated, if not planned outright.

Why the Coronation Mattered

- For the Pope, it meant security. By granting Charlemagne the imperial title, Leo bound the mightiest temporal authority in Christendom to the service of the Papacy.

- For Charlemagne, the coronation elevated his rule above other kings, placing him in a unique position as a protector of the Church and heir to Roman imperial dignity.

- For Europe, it inaugurated the institution later called the Holy Roman Empire, a political-religious framework that would persist, albeit with changing forms, for almost a thousand years.

Broader Historical Context

The attack on Pope Leo III was more than an isolated power struggle within Roman nobility. It represented:

- The Decline of Byzantine Influence in Italy – The Eastern emperors, based in Constantinople, could not prevent Roman nobles from turning against their pope, nor could they respond when the papacy reached out to the Franks. This event emphasized the papacy’s shift westward for support.

- The Increasing Role of the Franks – With Leo’s appeal to Charlemagne, the Carolingian dynasty established itself as the primary defender of Christendom in the West.

- Fusion of Religion and Politics – The mutual dependency between pope and emperor would shape medieval European politics. The question of “Who holds supreme authority: the spiritual pope or the temporal emperor?” would eventually ignite fierce conflicts in later centuries.

Historical Significance

The attack on Pope Leo and his rescue by Charlemagne are milestones because they illustrate how violence, politics, and religion overlapped in an age defined by fragility and transformation.

- Institutional Impact: The papacy’s reliance on Frankish kings gave rise to a precedent of secular rulers influencing church matters.

- Cultural Consequences: By supporting Leo, Charlemagne positioned himself not just as a king but as a new kind of Christian ruler, the prototype medieval emperor.

- Symbolism: Leo’s blinding attempt symbolized the attempt to silence the Church’s independence. His survival and restoration, by contrast, symbolized the endurance of papal authority through divine providence.

The Human Dimension

It is easy to view these events through political analysis alone, but they were also profoundly human. Leo, a man born outside aristocratic circles, endured humiliation and a near-fatal assault at the hands of his own city’s nobles. His flight to Charlemagne was an act of desperation, a plea for survival, but it also showed courage in trusting a foreign king for salvation.

Charlemagne, often remembered for his conquests, emerges in this episode as a mediator and guardian. His image as a Christian monarch was reinforced not only on the battlefield but in his role as protector of the pope.

The Long-Term Legacy

The partnership between Leo III and Charlemagne set into motion a legacy that would endure through the centuries:

- The Holy Roman Empire, claiming to be the heir to Rome, would dominate medieval European politics.

- The papacy, though weakened internally in 799, emerged with new spiritual authority, directly connected to shaping emperorship.

- The Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of learning and culture sponsored by Charlemagne, owed much of its legitimacy to his role as pope-appointed emperor.

Even centuries later, echoes of that Easter-time procession turned violent in 799 could still be felt across Europe’s evolving institutions.

Conclusion

The story of 799, when Pope Leo III was attacked in Rome and later rescued by Charlemagne, is much more than an episode of political intrigue. It marks a turning point in European history: it deepened the union between secular kingship and spiritual authority, elevated Charlemagne onto the world stage as the new Roman Emperor, and reaffirmed the pope’s position at the heart of Western Christendom.

Had Leo been permanently mutilated or deposed, the papacy might have entered decline or fallen under Byzantine or noble domination. Instead, thanks to Charlemagne’s intervention, the papacy was secured, and Western Europe entered a new phase of medieval civilization.