The moment the imperial regalia of the Western Roman Empire left Italy for Constantinople marked more than the quiet end of an empire – it signaled the death of a thousand-year idea. The diadem, purple cloak, orb, and sceptre that once embodied the majesty of Caesar now glimmered in the Eastern sun, far from their birthplace on the banks of the Tiber.

The Shadow After the Fall: The Western Empire in Ruin

By the late fifth century, the Western half of the Roman Empire had already become a hollow shell. Italy, once the heart of Roman civilization, had endured relentless invasions – Visigoths, Vandals, and finally Heruli – each blow cutting deeper into the dignity of a fading order. The imperial court in Ravenna clung to ceremony while mercenary kings commanded the legions. The last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was himself little more than a teenager, a puppet enthroned by his ambitious father Orestes.

When Odoacer, a Germanic general in Roman service, rebelled against Orestes in 476, the dream of the empire’s survival briefly flickered and died. Orestes was executed; Romulus Augustulus was spared but deposed. Yet what followed was not the dramatic collapse one might imagine – Rome did not burn. The Senate still met, taxes were still collected, and Italy remained governed under familiar institutions. But the office of “Emperor of the West” was gone. Odoacer, aware of the Eastern emperor’s authority, declared that one emperor was enough for both East and West and sent his envoys – and the imperial regalia – to Constantinople.

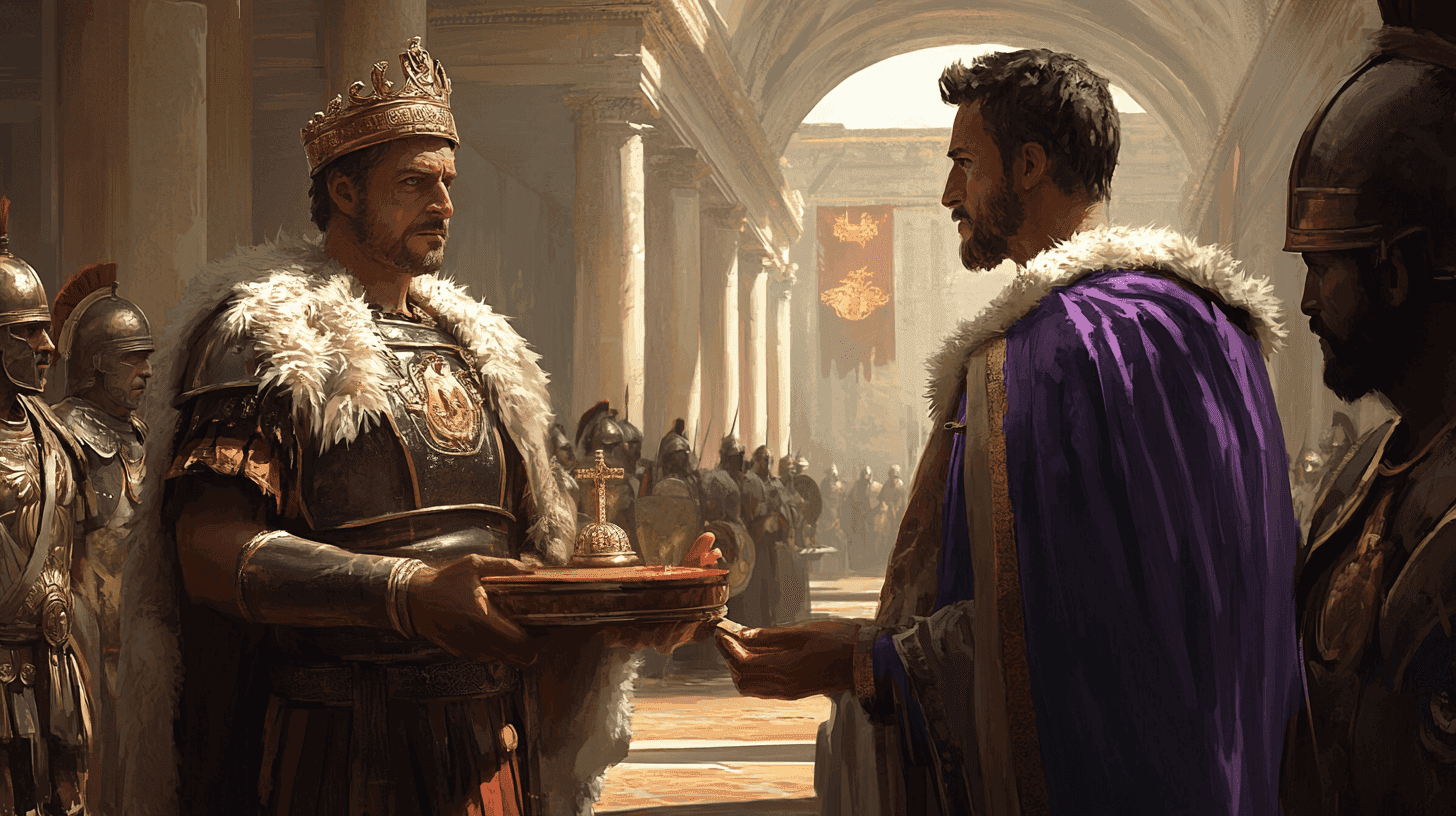

A Mission to the New Rome

It was an act both diplomatic and deeply symbolic. The envoys who carried the diadem, sceptre, and cloak across the Adriatic bore a message as transformative as any conquest: the West renounced its imperial claim. Zeno, the Eastern emperor ruling from Constantinople, received the message with political shrewdness. He accepted the regalia as tokens of unity: emblems that the Roman world, stretched across two continents, was once again united under one crown. But the gesture had deeper consequences than Zeno perhaps realized.

The sending of the regalia represented an acknowledgment that the imperial dignity now resided fully in the East. Constantinople, long called the “New Rome,” had not merely inherited the empire’s strength; it had supplanted the Old Rome’s claim to eternity. In that instant, Italy’s ancient lineage of imperial authority was extinguished, transformed from a living institution into a memory.

The Meaning of the Imperial Regalia

To understand the gravity of this transfer, one must appreciate what the imperial regalia represented. Since the days of Augustus, the trappings of the emperor’s authority carried almost mystical significance. The purple cloak or chlamys, the diadem of twisted gold, the golden orb symbolizing universal sovereignty – all were more than ornaments. They were the living symbols of divine imperium, of the emperor’s role as cosmic mediator between heaven and earth.

In the later centuries of the Roman Empire, these symbols acquired a quasi-sacred character, connecting the emperor’s rule with the order of the universe itself. When Odoacer’s envoys carried them across the sea, they were not simply handing over precious metals – they were transmitting legitimacy, the very spirit of empire. And once those symbols were in Constantinople, any notion of restoring a separate Western emperor became unthinkable. The office was dead; the idea was buried in the gleam of Zeno’s court.

Constantinople: The City That Survived

From the Eastern perspective, the reception of the Western regalia validated Constantinople as the true Rome. Founded by Constantine the Great on the Bosporus in 330 AD, the city had long outshone her older sister. Surrounded by formidable walls and enriched by trade, Constantinople thrived even as the western provinces fell to invading tribes. Its Greek-speaking populace, sophisticated bureaucracy, and imperial ceremonies came to define what it meant to be Roman in the later age.

After 476, there was no longer any doubt where Rome’s destiny lay. Latin might fade, territories might shrink, but the Eastern emperors would rule for nearly a thousand years more, claiming uninterrupted descent from Augustus. From Zeno to Constantine XI, their authority remained bound to the regalia and what it symbolized – the unbroken line of Roman sovereignty now rooted in the East.

Italy After the Regalia

Meanwhile, in Italy, Odoacer ruled in the emperor’s name but without the emperor’s title. He styled himself Patricius of Italy, formally a servant of the Eastern emperor, though he governed independently. His rule preserved a surprising degree of Roman continuity – taxation, administration, and senatorial privilege continued much as before. Yet every official decree, every minted coin, carried the silent absence of imperial Rome.

When Theoderic and his Ostrogoths later conquered Italy under imperial sanction, they too acknowledged Constantinople’s theoretical supremacy even as they ruled as kings in practice. No Roman emperor ever returned to govern Italy directly. The imperial regalia, long kept in the palaces of Constantinople, had sealed that fate.

The Philosophical Death of Rome

Modern historians often debate whether 476 truly marked the “fall” of Rome. After all, daily life carried on; Roman law endured; Christianity filled the vacuum of imperial ideology. But the sending of the regalia was more than administrative convenience – it was an act of metaphysical surrender. In relinquishing the purple and sceptre, Italy confessed that imperial destiny had passed elsewhere.

Rome was no longer the axis of the world but a relic, a holy city whose glory lay in its ruins. The Senate that once decided the fate of kings became a municipal council. Even the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, gradually rose to fill the symbolic void left by the vanished emperors, inheriting their mantle of universal authority in a spiritual form. In this way, the empire’s death fertilized the soil for the medieval order that would dominate Europe for centuries.

Constantine’s Legacy Fulfilled

Ironically, the final transmission of the regalia fulfilled Constantine the Great’s vision far more completely than he likely ever intended. When he founded his new capital on the Bosporus, Constantine imagined a Christian Rome freed from the pagan decadence of the old city – a purified empire reborn in faith. By the late fifth century, that dream had matured into reality. Constantinople alone held the emperor’s court, the imperial treasure, and the religious aura of divine kingship. The regalia’s arrival there affirmed this transformation: Old Rome had died so that New Rome could live.

The Eastern court commemorated the event through renewed ceremonial splendor. The emperor appeared in magnificent processions, his vestments adorned with pearls and icons. Palace rituals, carefully codified by later writers like Constantine Porphyrogenitus, drew directly from the sacred symbolism the regalia embodied. The Western swords and crowns became relics of a bygone world, now absorbed into the eternal rhythm of Byzantium.

The Silent Voyage: Myth and Memory

No contemporary account describes in detail the voyage of the imperial regalia from Italy to Constantinople, but later chroniclers wove it into the mythic texture of Europe’s imagination. Some imagined a solemn procession leaving Ravenna’s harbor under gray skies, bearing the diadem across the sea as monks and soldiers watched in silence. Others spoke of the regalia entering the Golden Horn under the rising sun, greeted by chanting clergy and the city’s resplendent domes. Whether such scenes unfolded or not, they captured the deeper truth – that the age of emperors in Italy ended not with a roar of battle, but with a quiet act of transition.

In medieval lore, the regalia themselves acquired an almost relic-like aura, said to be kept in the Imperial Treasury and used only at coronation ceremonies. Over time, their origins blurred: some said they came directly from Caesar, others from Constantine or even Augustus himself. But all agreed on their meaning – they were the tangible thread connecting the later Byzantine emperors to the divine rulers of Rome’s golden age.

From Empire to Christendom

The political vacuum left by the Western Empire’s disappearance gave rise to something profoundly new: Christendom. The Church, already the most stable institution in the West, began to assume the moral and cultural leadership once held by the Caesars. Bishops took over civic administration; monasteries became economic centers; popes negotiated treaties with kings. And above them all loomed the memory of Rome – no longer a living empire but a sacred inheritance.

When, in the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 AD, Pope Leo III revived the imperial title in the West, it was an act of nostalgia as much as politics. The Frankish emperor’s crown claimed continuity with the ancient Caesars, but the true regalia of Rome remained in Constantinople. The Holy Roman Empire, for all its grandeur, was born in the shadow of that lost authenticity. The act of 476 had, in effect, drawn a permanent line between the classical and the medieval worlds.

The Byzantine Custody of Rome’s Spirit

In the centuries that followed, Byzantium continued to see itself as the sole heir to Rome. Its emperors called themselves Basileus ton Rhomaion – Emperor of the Romans – long after the Latin West had forgotten the language. In art, law, and ceremony, the Byzantines consciously preserved the Roman identity. Justinian’s codification of law, his rebuilding of Hagia Sophia, and even his campaigns in Italy were all expressions of an imperial mission stretching back to Augustus.

Yet this Roman identity would itself evolve. By the time of Heraclius in the seventh century, Greek had replaced Latin in administration, and the empire’s citizens called themselves Romans but spoke Greek, worshipped in Eastern rites, and looked eastward for trade and culture. The regalia that had once crossed the Adriatic thus came to symbolize not merely continuity but transformation – the rebirth of Rome in another language and tradition.

The Final Echo: 1453 and the End of an Idea

Nearly a thousand years after Odoacer’s envoys docked at Constantinople, the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, donned the imperial regalia to defend his city against the Ottoman Turks. As the walls of Constantinople fell in 1453, those same symbols – the purple robe, the diadem, the sacred orb – disappeared into legend. Many medieval chroniclers saw this as the final extinguishing of the Roman Empire. From Augustus to Constantine XI, an unbroken chain of emperors had endured for nearly fifteen centuries, but now the line was truly severed.

In that sense, the regalia’s first transfer from Italy to Constantinople marked Rome’s political death, while their loss to the Ottomans centuries later marked the death of its spirit. Yet both deaths gave birth to new worlds: medieval Europe from the first, and Renaissance humanism from the second.

Epilogue: Rome Without an Emperor

When the Senate of Rome declared to Emperor Zeno that there was “no need for two emperors,” they could not have foreseen the vast world their statement would help create. Their gesture was humble, almost bureaucratic, yet it dismantled the ancient order more thoroughly than any barbarian invasion. From that moment on, “Rome” existed in many guises: as a memory, as a church, as a word of power, as the dream of restoration that haunted kings and popes alike.

The real Rome -the Rome of emperors, adorned with diadem and orb – had sailed eastward. Yet in another sense, it never truly left. Its laws, institutions, and faith persisted in Western thought, and every claim to empire – Byzantine, Carolingian, Ottoman, or even modern – drew legitimacy from its shadow.

Thus the final transmission of the imperial regalia was both an end and a beginning: the death of an empire, the birth of heritage; the extinguishing of a crown, the lighting of a thousand thrones.