The Siege of Constantinople in 717-718 stands as one of history’s most dramatic battles for survival – a clash that decided the fate of empires and reshaped the trajectory of European and Islamic history. Over thirteen turbulent months, the majestic Byzantine capital became the prize in a grueling contest between the adventurous Umayyad Caliphate and the tenacious defenders of Eastern Christendom.

Background: Two Decades of Tension

After the end of the first Arab siege (674–678), Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire enjoyed a brief respite – but this peace was delicate. The Umayyad Caliphate, energized after its own civil war, renewed hostilities and began a relentless campaign of raids, expansion, and encroachment into Byzantine frontier lands. By the second decade of the 8th century, the Arab tide had swept through Armenia and the Caucasus, bringing hard-fought border fortresses and towns under Umayyad control. Byzantine defenses, strained by near-constant coups and internal turmoil, struggled to stem the relentless pressure. In this climate, the idea of a final assault on the imperial capital itself took shape – turning Constantinople into the ultimate prize for a Caliphate at the peak of its ambition.

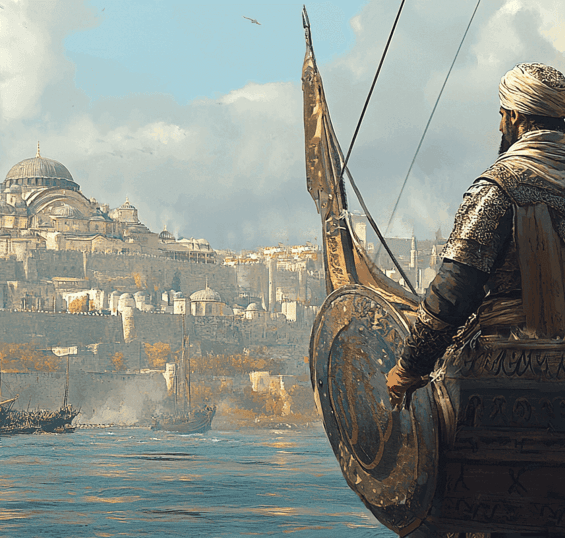

The Players: Armies and Alliances

Preparations for the 717 campaign were staggering in their scale. Contemporary sources, though prone to exaggeration, suggest the Arabs fielded tens of thousands of troops and a fleet perhaps numbering over 1,800 ships, all entrusted to the command of Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik. The siege army was heavily equipped – not just with weapons, but also with agricultural supplies, intended to settle in for a long blockade and even sow crops around the city. The Byzantine defenders, meanwhile, counted on their famous fortifications – the Theodosian Walls – and on key allies, most notably the First Bulgarian Empire whose ruler, Tervel, would play a dramatic role in the battle’s outcome.

The Opening Moves: Outmaneuvering and Deceit

Civil war and palace intrigue within Byzantium shaped the earliest moves. The Arabs tried to exploit the empire’s chaos by allying with Leo III the Isaurian, a powerful general who seemed open to negotiation but ultimately deceived them to gain the throne and unite the city’s defense. As Maslama led the Umayyad army from Asia Minor into Thrace, they ravaged the countryside and cut Constantinople off from its hinterlands, surrounding it on land with dual siege walls. By early September, the full weight of the Arab fleet was brought to bear, aiming to block the city’s lifeline – the Bosphorus and Golden Horn – from seaborne support.

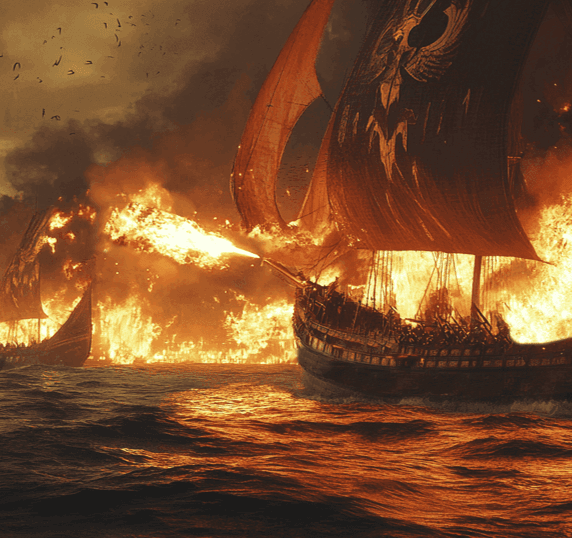

Greek Fire and Naval Brilliance

The greatest weapon in the Byzantine arsenal was not a sword or a wall, but science itself – a secret blend known as Greek fire. As the Arab fleet attempted to close in, Byzantine fire-ships equipped with bronze siphons unleashed torrents of napalm-like flames, instantly destroying scores of enemy vessels. This stunning demonstration of technological and tactical superiority, combined with the raising of the great chain across the Golden Horn, crippled the Umayyad attempt to blockade the city by sea. The Byzantines retained their crucial supply channels, while the besieging army outside the walls soon faced hunger and pestilence.

Winter of 717–718: Hunger, Disease, and Desperation

The full fury of nature joined the struggle in the winter of 717-718. Heavy snow blanketed the Arab camp for months, cutting off foraging and leading to horrifying conditions: famine, epidemics, and desperation. Contemporary accounts describe soldiers eating their horses and camels, scouring the frozen ground for shoots, and even turning to acts of cannibalism. Starvation sapped the vigor and discipline of the besiegers, while within the city, Leo III orchestrated ruses and negotiations that sowed further confusion among the attackers.

Reinforcements and Revolts: The Turning Point

Hoping to break the deadlock, the Umayyad Caliph Umar II sent massive reinforcements and fresh fleets from Egypt and North Africa, packed with supplies and new crews. But the tide turned unexpectedly: many of the ships’ crews, Christian Egyptians, defected to the Byzantine side upon arrival. Armed with intelligence and leveraging their mastery of Greek fire, the Byzantines attacked and destroyed the new fleets, effectively ending the possibility of a renewed naval siege. Meanwhile, a new Arab army marching overland was ambushed and routed. The Bulgars, bound by treaty to Leo III, launched a deadly attack on Arab rear lines. The siege, already faltering, now broke completely.

Retreat and Ruin: The End of the Siege

On August 15, 718, exactly one year after the siege began, Maslama ordered a retreat. The battered remnants of his army and fleet withdrew from Thrace and sailed for home, only to suffer further disasters en route – ships destroyed by storms, volcanic ash, and Byzantine attacks. Fewer than a handful of ships are reported to have reached the safety of Syria, and the campaign cost the Umayyads dearly, with some chroniclers placing casualties in the hundreds of thousands. For the Byzantines, the day was commemorated as a miraculous victory, attributed to divine intervention and celebrated as the feast of the Dormition of the Theotokos.

Aftermath: A Shifting World

The financial and military losses weakened Umayyad control and morale, triggering fiscal strain and opposition within their domains. The immediate threat to Byzantium was vanquished, and though Arab raids would continue, never again would Constantinople face such a direct siege from the Caliphate.

The Byzantine frontier stabilized, and the empire’s survival ensured that Eastern Christianity and its unique culture would endure for centuries more. The Caliphate lost prestige and strategic focus, its expansion west halted not just here, but at Tours in 732, where Charles Martel checked the Muslim advance into Francia. Historians judged the dual defense of Christendom at Constantinople and Tours as decisive in the shaping of medieval Europe.

Historical Significance: Why It Matters

The 717–718 siege was more than a battle for one city – it was an existential struggle whose outcome fashioned the destiny of continents. The survival of Constantinople created a bulwark against further Islamic expansion from the East, allowing the medieval Christian kingdoms of Europe to develop in their own arc. Military historians rank the battle among the great world-changing confrontations, a “decisive date” on par with Marathon or Tours. Without it, the cultural and religious landscape of Europen, as well as political developments from the Carolingians to the Renaissance, might have taken a profoundly different path.