The story of the Jutes in Britain is an often overlooked chapter in the island’s early Dark Age history. While the Angles and Saxons tend to dominate narratives of post-Roman Britain, the Jutes played a significant role in shaping the cultural and political landscape of what would eventually become England.

Origins and Migration

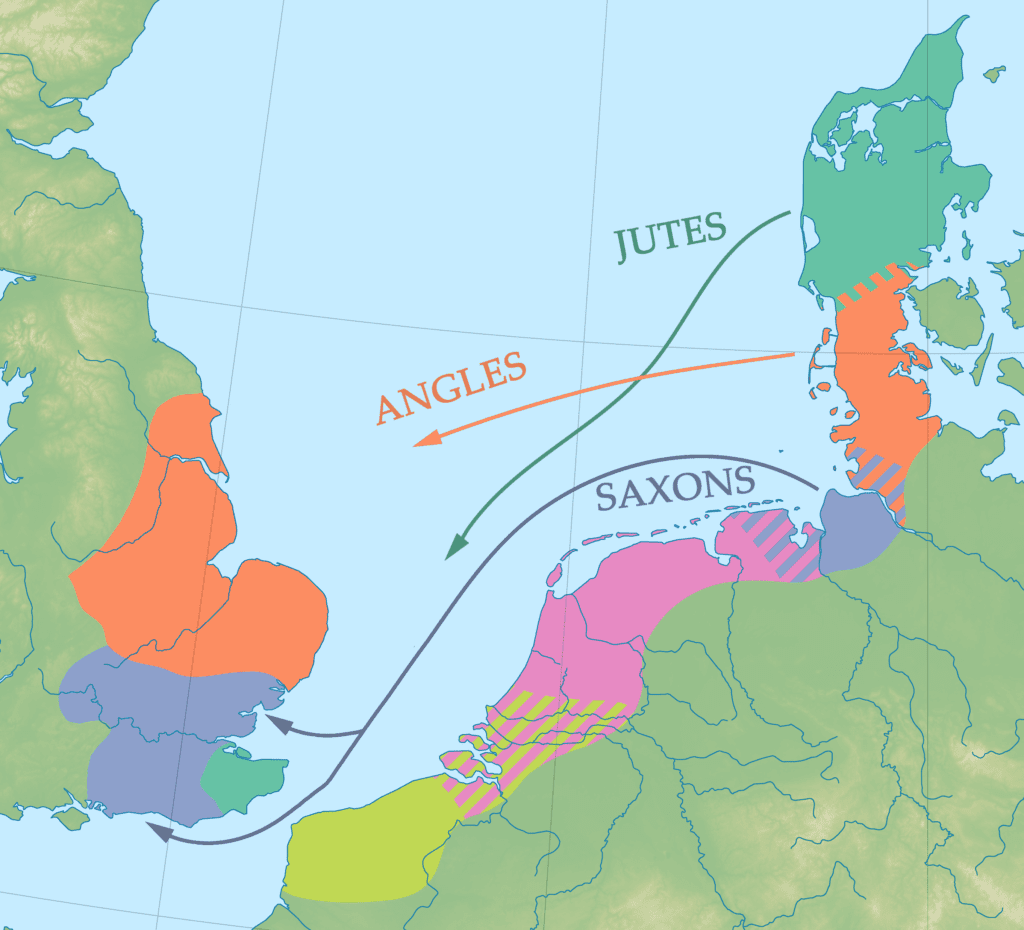

The Jutes were one of the Germanic tribes that settled in Britain after the departure of the Romans in the 5th century CE. According to the Venerable Bede, an 8th-century English monk and historian, the Jutes were one of the three most powerful Germanic nations to settle in Britain, alongside the Angles and Saxons.

Traditionally, the Jutes were believed to have originated from the Jutland peninsula in modern-day Denmark. However, recent archaeological evidence has cast doubt on this assumption. Analysis of grave goods from the period shows strong links between East Kent, southern Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, but little connection to Jutland. Some historians now suggest that the Jutes who migrated to Britain may have come from northern Francia or Frisia (now the Netherlands) instead.

Settlement in Britain

According to Bede, the Jutes primarily settled in three main areas of southern Britain: the Isle of Wight, Parts of Hampshire and Kent. The latter would become the Kingdom of Kent, one of the most powerful and influential of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Source: Wikipedia

The Kingdom of Kent

The story of the Jutish Kingdom of Kent begins with the legendary figures of Hengist and Horsa. According to historical tradition, these Jutish brothers were invited by the Romano-British ruler Vortigern to help defend Britain against Pictish invasions from the north. They landed at Wippidsfleet (Ebbsfleet in Kent), and went on to defeat the Picts wherever they fought them. Hengist and Horsa sent word home to Germany asking for assistance. Their request was granted and support arrived. This invitation, whether historical fact or later embellishment, marks the beginning of a significant shift in the power dynamics of post-Roman Britain.

The initial settlement of the Jutes in Kent was likely a complex process, involving a mix of migration and integration with the existing Romano-British population. One of the earliest recorded diplomatic moves of the Jutish leaders was Hengist’s alleged arrangement of a marriage between his daughter and Vortigern. By creating familial ties with the existing power structure, the Jutes were able to solidify their position and gain legitimacy in the eyes of both their followers and the local population.

The initial cooperation between the Jutes and Britons did not last long. As more Jutish settlers arrived, tensions grew, eventually leading to open conflict. The Jutes, leveraging their military skills and increasing numbers, began to expand their control beyond their initial base on the Isle of Thanet. This period of expansion was likely characterized by a series of battles and skirmishes against both British forces and rival Germanic groups. The Jutes’ success in these conflicts allowed them to establish control over what would become the Kingdom of Kent, stretching from the Channel coast to the banks of the Thames.

Interestingly, the rulers of Kent did not explicitly identify themselves as Jutes. Instead, they used titles such as “Kynges Cantwaras” or “Kings of the people of Cantiaca,” referring to the pre-existing Brythonic/Roman name for the area. This suggests that the Jutish settlers in Kent may have integrated themselves into existing communities rather than establishing an entirely new political entity.

The Kingdom of Kent reached its zenith under the rule of King Æthelberht, who reigned from around 580 to 616 AD. He is recorded as holding the title of Bretwalda, indicating his status as the most powerful ruler among the southern Anglo-Saxon kings. Æthelberht’s reign was characterized by astute diplomacy, particularly in his relations with the Frankish kingdoms across the Channel.

The Frankish princess Bertha arrived in Kent around 580 to marry King Æthelberht. Bertha was already a Christian and had brought a bishop, Liudhard, with her across the Channel. Æthelberht rebuilt an old Romano-British church and dedicated it to St Martin allowing Bertha to continue practising her Christian faith. In 597 Pope Gregory I sent Augustine to Kent, on a mission to convert the Anglo-Saxons. Æthelberht was the first of the Anglo-Saxon rulers to be baptised.

Æthelberht’s marriage to Bertha, a Christian Frankish princess, was a masterstroke of diplomatic maneuvering. This union not only strengthened Kent’s ties with the powerful Frankish realms across the Channel but also paved the way for the introduction of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. This event had far-reaching consequences, establishing Kent as the birthplace of English Christianity and enhancing its prestige among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

As Kent’s power waxed and waned, it faced increasing pressure from neighboring kingdoms. The rising power of Mercia in the 7th century posed a particular threat. In 676 AD, the Mercian king Æthelred invaded Kent, causing significant destruction. Subsequently, Mercia exerted increasing influence over Kent. While Kent maintained its own kings, they were often subject to Mercian overlordship, and Kent’s role shifted from that of a dominant power to a subordinate kingdom within the Mercian sphere of influence.

The late 8th and 9th centuries brought a new threat in the form of Viking raids. Kent’s coastal position made it vulnerable to these attacks and the need to defend against these incursions strained the kingdom’s resources and undermined its stability. As Mercia’s power also waned in the face of Viking attacks, Wessex emerged as the dominant Anglo-Saxon kingdom. Under kings like Egbert and Alfred the Great, Wessex gradually absorbed the other southern Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, including Kent. By the mid-9th century, Kent had lost its independence, becoming part of the larger Kingdom of Wessex

The Fading of Jutish Identity

Despite their initial prominence, the distinct Jutish identity seems to have faded relatively quickly. By the 9th century, when Kent had become a sub-kingdom of Wessex, it was likely considered “Saxon” for most purposes. Certainly over time, the distinctions between Jutes, Angles, and Saxons became less pronounced as these groups intermarried and developed a more unified “English” identity.