In the tumultuous world of 9th century Ireland, few figures loom as large as Bardr mac Imair, the Viking sea-king who ruled Dublin from approximately 873 to 881 CE. Known by various names including Barid mac Imair, Barith, and Baraid, this Norse warrior left an indelible mark on Irish history through his military campaigns, political maneuverings, and role in the burgeoning slave trade.

To fully appreciate the significance of Bardr mac Imair’s reign, it’s essential to understand the historical context in which he operated. The 9th century was a period of great change and conflict in Ireland, with Viking invasions and settlements dramatically altering the political and social landscape.

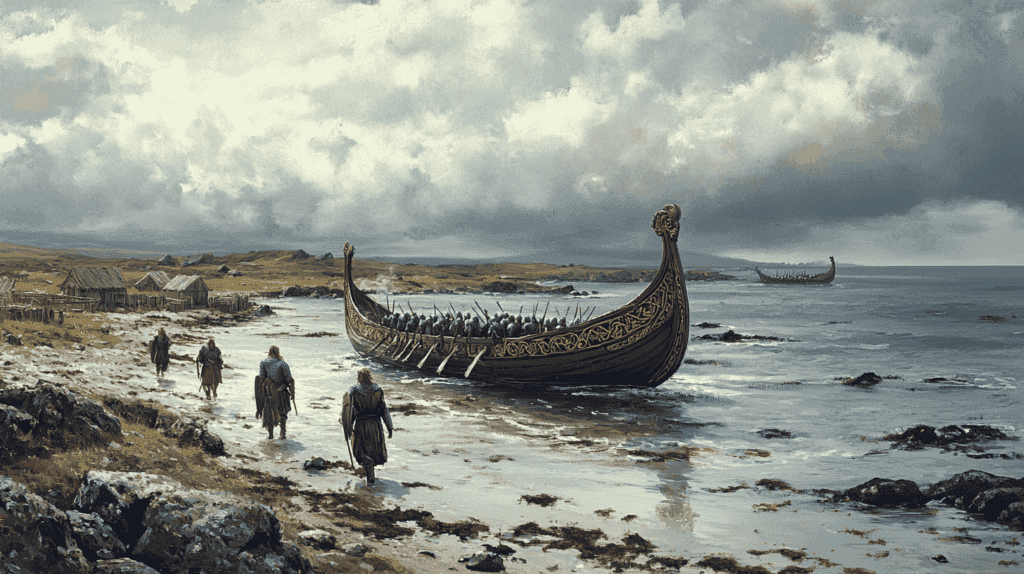

The Vikings, or Norsemen, had first appeared on Irish shores in the late 8th century. Initially, their raids were sporadic and focused on easily accessible coastal targets. However, by the mid-9th century, they had established permanent settlements, with Dublin emerging as the most important of these Norse-Gael kingdoms.

Bardr’s father, Imair, was instrumental in establishing the Uí Imair (descendants of Imair) dynasty, which would dominate the Irish Sea region for generations. Bardr’s reign, which began around 873 CE with the death of his father, therefore, represented a crucial period of consolidation and expansion for this Viking dynasty.

Military Campaigns and Raids

Bardr’s reign was characterized by frequent military campaigns against Irish monasteries, religious institutions, and other communities. These raids were primarily motivated by the desire for plunder, which was then brought back to enrich Dublin.

One of Bardr’s most notable campaigns occurred in 872 CE when he raided Moylurg and the islands of Lough Ree. This expedition, recorded in the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, demonstrates the Viking king’s ability to navigate Ireland’s inland waterways, a skill that would prove crucial in many of his military endeavors.

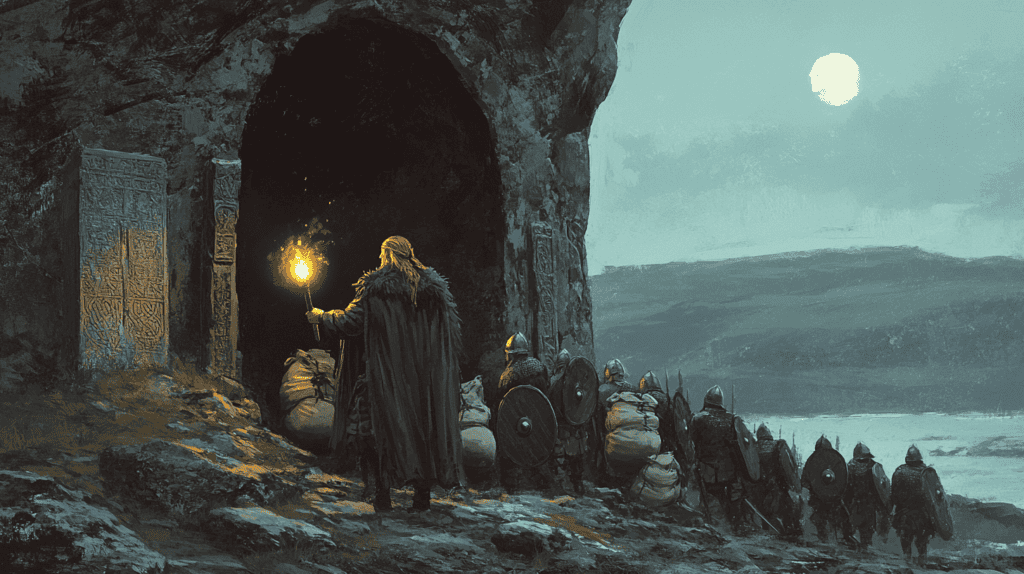

The following year, Bardr led a significant military expedition that solidified his reputation as a “Viking sea-king”. In 873 CE, he commanded a great fleet from Dublin (Áth Cliath) and sailed westward to the Kingdom of Munster. This campaign was notable for its audacity and unconventional tactics. The Annals of Inisfallen record that Bardr “plundered Ciarraige Luachra underground, i.e., the raiding of the caves”. This likely referred to the plundering of ancient tombs for treasure. In this, Bardr seemed to revert to older Viking tactics, echoing the 863 CE expedition led by his father Imair and uncles Amlaib and Auisle into the Boyne Valley, where they had raided megalithic tombs such as Newgrange and Knowth.

Another notable campaign in Bardr’s military career was the sack of Armagh in 879 CE. Armagh held immense religious and political significance as the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. By targeting this city, Bardr struck at the heart of Irish Christian culture and governance. The attack on Armagh likely yielded valuable loot and hostages, further enhancing Dublin’s power and influence.

The Vikings brought with them advanced shipbuilding technology and naval tactics that allowed them to navigate not just the seas around Ireland, but also its rivers and lakes. This ability to strike deep into the Irish interior, plundering efficiently and retreating before a significant defense could be raised, gave them a significant advantage over their opponents and was a hallmark of Viking warfare in Ireland.

Political Maneuverings

While Bardr’s military exploits are well-documented, his political acumen should not be overlooked. The Fragmentary Annals suggest that Bardr fostered a son of Áed Findliath, the overking of the Northern Uí Néill. This practice of fosterage was commonly used in Ireland to strengthen ties between ruling families, indicating that Bardr may have been attempting to integrate himself into the Irish political elite.

The Slave Trade and Economic Impact

Under Bardr’s reign, Dublin continued to be a major center of the slave trade, a practice that had been established during the rule of his predecessors. In fact, the sale of slaves generated more wealth for the growing city than any other commodity.

Bardr’s activities in Connacht, for instance, focused heavily on capturing citizens for the slave trade. This practice likely contributed to the hostility he faced from the men of Connacht, who at one point attempted to kill him.

Challenges and Conflicts

Despite his military successes, Bardr’s reign was not without its challenges. In 875 CE, his cousin and possible co-ruler Oistin was “deceitfully” killed by a figure known as “Albann,” generally believed to be Halfdan Ragnarsson. This event may have been part of an attempt by Halfdan to claim Dublin for himself.

While Halfdan’s initial attempt seems to have failed, he tried again in 877 CE. This time, he fell in battle against an army of “fair foreigners” at the Battle of Strangford Lough. The Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib identifies Bardr as the leader of these “fair foreigners,” and states that he was wounded in the battle “so that he was lame ever after”.

Legacy and Death

Bardr mac Imair’s reign came to an end in 881 CE, following a raid on the oratory of St. Cianan (or St. Ciaran, depending on the source) in Dunleek, Meath. His death, through drowning or burning, was attributed to divine retribution, seen as punishment for his desecration of sacred sites.

Despite the violence that characterized much of Bardr’s reign, there’s evidence to suggest that he, like many Viking rulers in Ireland, was not opposed to cultural exchange and even assimilation with the native Irish population. Over time, many Viking settlers in Ireland adopted Gaelic customs, language, and even names. This process of cultural exchange would eventually lead to the emergence of the Norse-Gael culture, a unique blend of Norse and Gaelic elements that would characterize much of medieval Irish society.

Barid turns up in my family tree as my 36th great grandfather and part of the reason my surname is as it is today: MacLachlan. I’m missing some bits and branches but Barid remains a steady beginning to half of my family tree.