The year 867 CE marked a turning point in the history of the Byzantine Empire. In that year, Basil I, a man of humble origins, seized the throne and established the Macedonian dynasty, heralding a period of renewed strength, cultural flourishing, and military expansion that would last for nearly two centuries.

The Rise of Basil I: From Peasant to Emperor

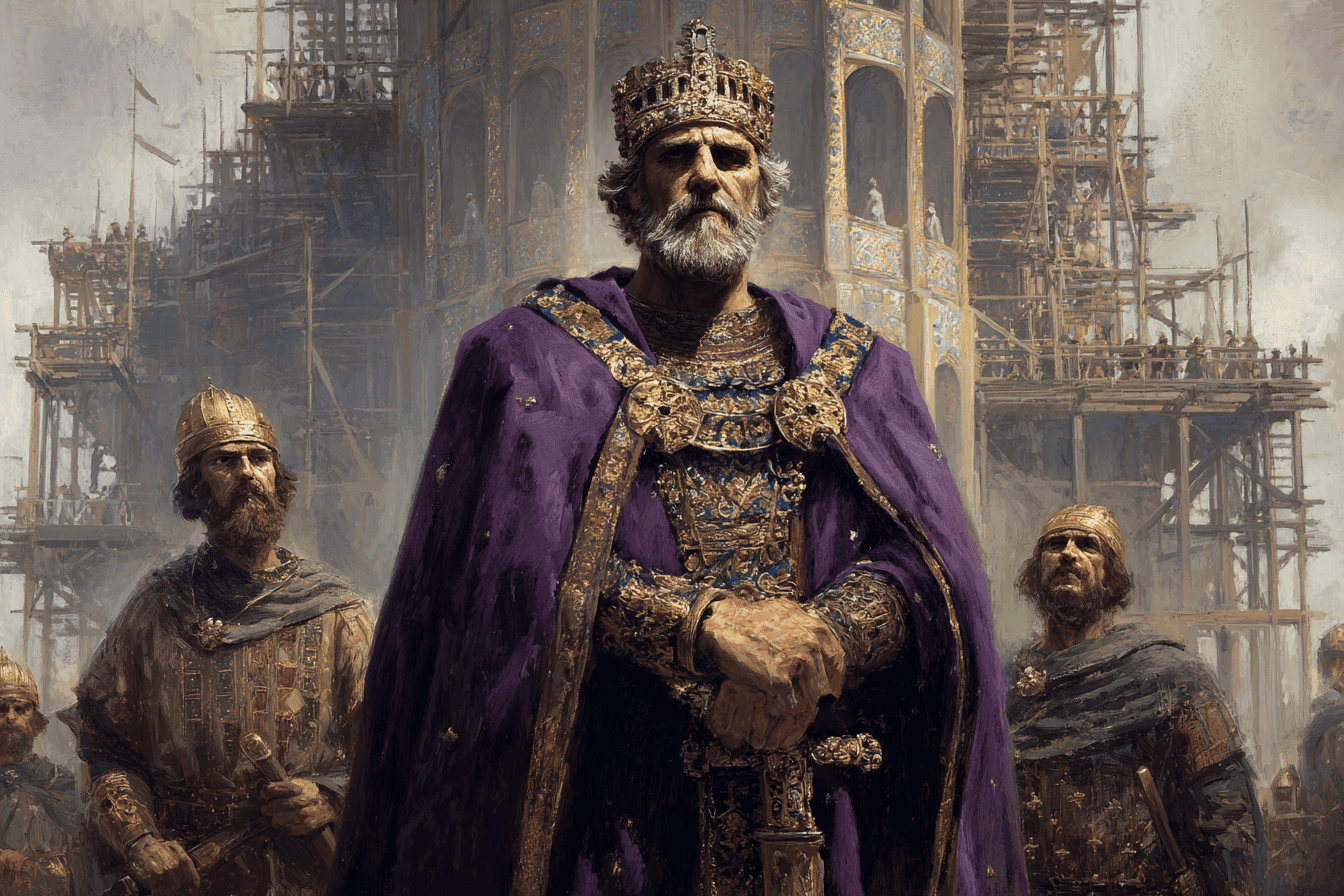

Basil I was born in the Byzantine province of Macedonia, likely between 826 and 835 AD, to a peasant family that may have had Armenian roots. His early life was unremarkable, but his ambition and physical prowess set him apart. Basil’s journey from obscurity to the imperial throne is a testament to the social mobility that was possible – albeit rare – in the complex world of Byzantium.

Basil’s fortunes changed when he caught the eye of Emperor Michael III, who was known for his unconventional lifestyle and lack of interest in administrative duties. Basil rose rapidly through the ranks, eventually marrying Michael’s mistress, Eudokia Ingerina, on the emperor’s own orders. In 866, Michael proclaimed Basil co-emperor, a move that would ultimately seal his own fate.

The immediate trigger for the assassination was Michael’s shifting favor. In the weeks before his death, Michael had begun to shower attention on another courtier, Basiliskianos, whom he reportedly threatened to elevate as yet another co-emperor. This move alarmed Basil, who feared for his position and the future of his own family’s claim to the throne. The threat of Basiliskianos’ rise was not merely a personal insult but a direct challenge to Basil’s carefully laid plans for succession.

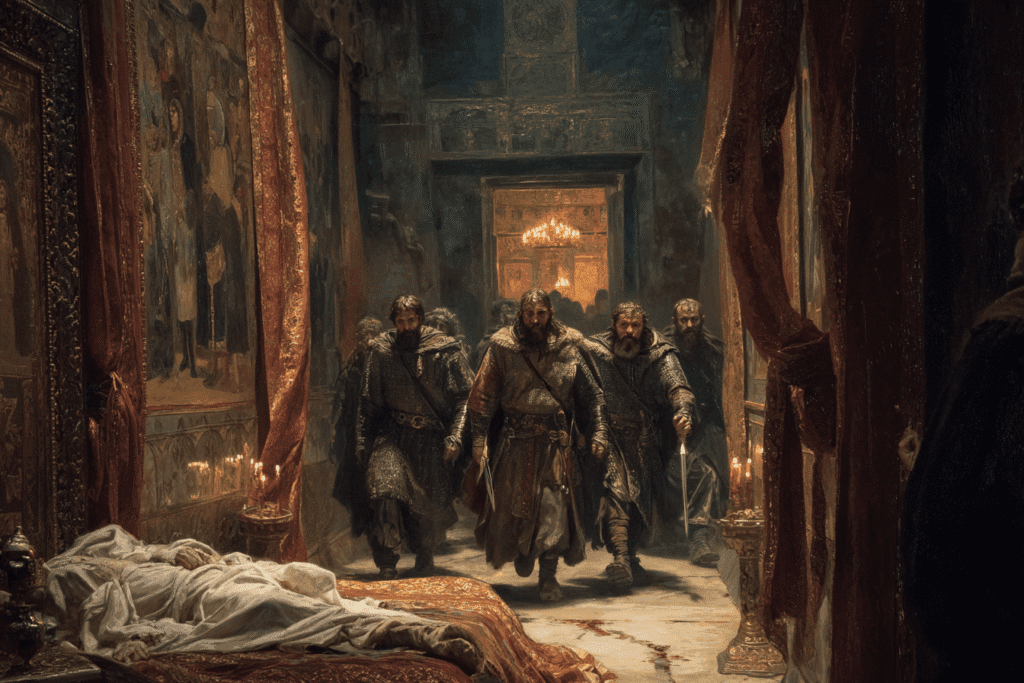

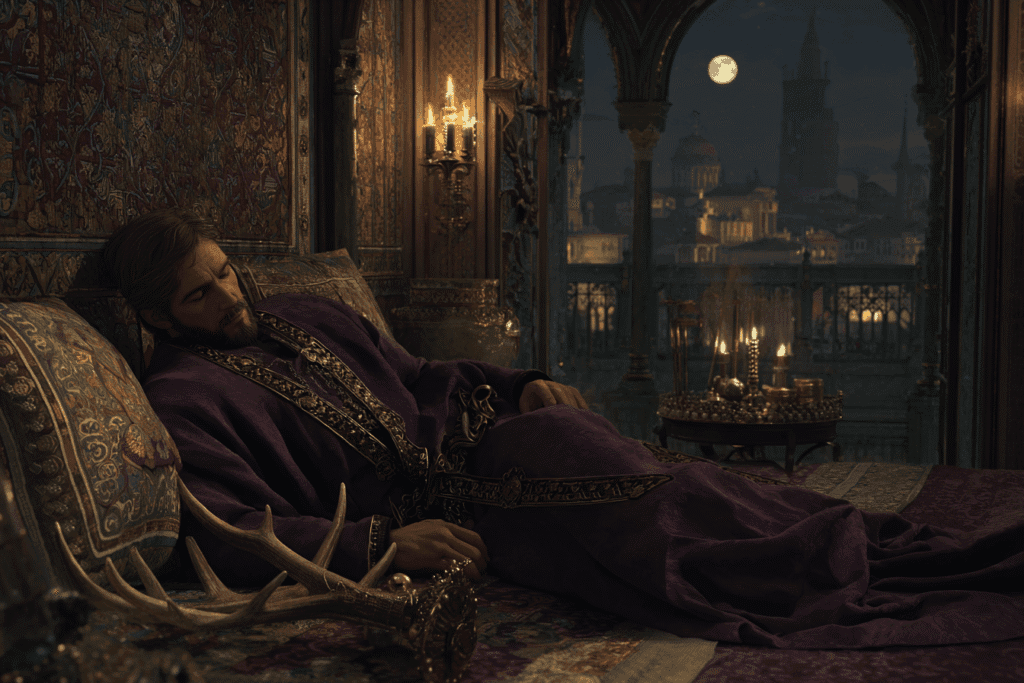

On the night of the assassination, Michael had indulged in a drinking bout – a habit that had earned him the disparaging epithet “the Drunkard” among later historians, though this portrayal may have been exaggerated by his detractors. Inebriated and vulnerable, he retired to his bedchamber, unaware that his trusted co-emperor had already set the wheels of treachery in motion. Basil, accompanied by a group of male relatives and accomplices, approached the emperor’s private quarters. The locks had been tampered with, and no guards stood in their way – a testament to the careful planning and insider knowledge that made the plot possible.

Inside the chamber, Michael lay insensible, defenseless against the coming violence. The actual killing was carried out by a man named John of Chaldia, whose method was both symbolic and gruesome: he severed both of Michael’s hands with a sword before delivering the fatal thrust to his heart. The mutilation of the emperor’s hands may have been intended to symbolize the severing of Michael’s power or to serve as a warning to would-be challengers. With Michael dead and Basiliskianos presumably eliminated as well, Basil emerged as the sole surviving emperor, his path to absolute power now clear.

The Reign of Basil I (867–886)

Despite his lack of formal education and administrative experience, Basil I proved to be an effective ruler. He was deeply religious and sought to present himself as a pious and orthodox emperor, dedicating his crown to Christ at his coronation. One of his most significant achievements was the overhaul of Byzantine law. He initiated the codification and revision of legal texts, a monumental project that would be completed by his successor, Leo VI, and become known as the Basilika. This legal code would remain the foundation of Byzantine law for centuries.

Basil also focused on ecclesiastical policy, maintaining good relations with Rome while asserting imperial control over the church. He exiled the controversial Patriarch Photios and restored Ignatios, whose claims were supported by the Pope. This move helped to ease tensions between the Eastern and Western churches, at least temporarily.

Basil I was also a patron of the arts and architecture. He oversaw the construction of the Nea Ekklesia cathedral and the palatine hall Kainourgion, symbols of the empire’s renewed confidence and piety. His reign set the stage for the cultural revival that would characterize the Macedonian dynasty.

The Macedonian dynasty is often associated with the “Byzantine Renaissance” or “Macedonian Renaissance,” a period of renewed interest in classical scholarship, philosophy, and the arts. Ancient texts were preserved and recopied, education flourished, and Byzantine art reached new heights of sophistication. The empire’s cities expanded, and affluence spread across the provinces as production and trade increased.

Military and Foreign Policy

Eastern Front: Subjugation of the Paulicians and Raids into Arab Territory

Basil’s early years on the throne were dominated by the need to neutralize the Paulicians, a heretical sect based in Tephrike on the upper Euphrates. The Paulicians had long been a thorn in the side of the empire, raiding deep into Anatolia, even sacking Ephesus and forging alliances with the Arabs. Basil recognized that their continued presence threatened the stability of the eastern frontier and endangered Byzantine efforts to reclaim lost territory. In 872, Basil’s general, Christopher, led a decisive campaign against the Paulicians, culminating in the death of their leader, Chrysocheir, and the subjugation of their state. This victory removed a major internal threat and allowed Basil to focus on external enemies.

With the Paulicians subdued, Basil turned his attention to the Arabs. Raids across the eastern frontier into the Euphrates region became a hallmark of his military strategy. In 873, Byzantine forces captured Samosata, a key city in eastern Anatolia. This was followed by further incursions into Cilicia and northern Mesopotamia, regions that had long been under Arab control. By 879, these territories were pillaged, and the Byzantines had reestablished a foothold in areas that had been lost for generations. Although Basil did not succeed in taking Melitene, a major Arab stronghold, his campaigns destabilized Arab rule and set the stage for future Byzantine advances.

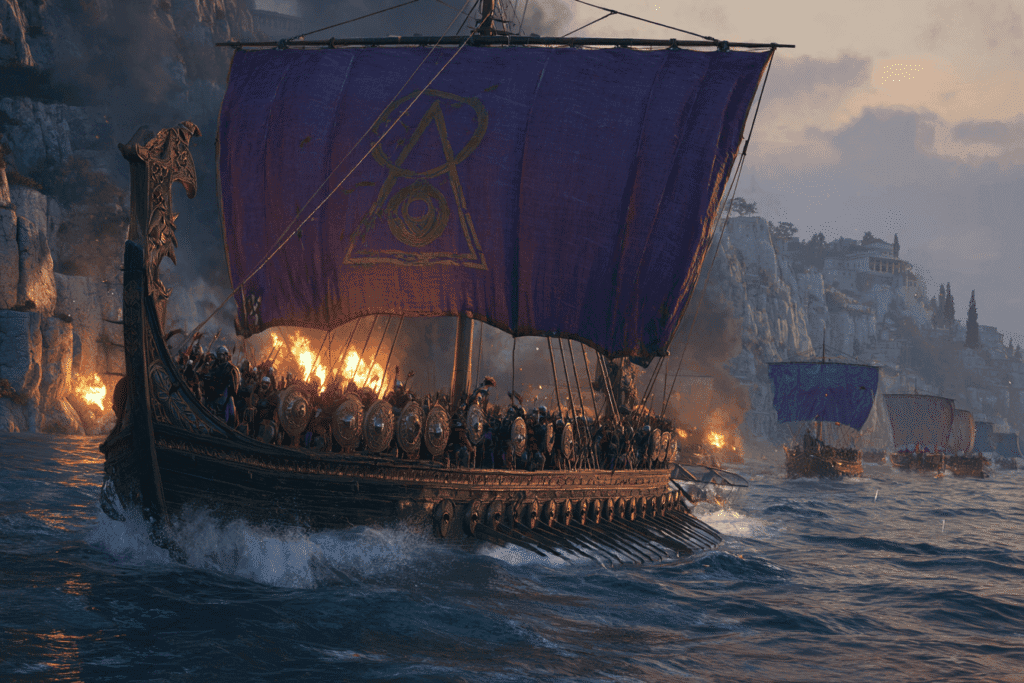

Naval operations also played a crucial role in Basil’s eastern strategy. In 873, he defeated the Cretan Arab fleet, weakening Arab dominance in the eastern Mediterranean. Two years later, in 875, Byzantine forces captured Cyprus, a strategically vital island that had been a bone of contention between the empire and the caliphate. These victories restored Byzantine naval prestige and secured vital sea lanes for trade and military operations. However, the gains were not always permanent; the empire’s hold on Cyprus and other territories remained tenuous, and future emperors would have to continue the struggle.

Western Front: Battles for Southern Italy and the Adriatic

While Basil’s efforts in the East were significant, his campaigns in the West were equally ambitious. The Arab emirates of Bari and Taranto had established themselves as piratical powers, threatening Byzantine interests in southern Italy and the Adriatic. Basil recognized the importance of reasserting imperial control over these regions, both to secure the empire’s western flank and to protect vital trade routes.

Basil pursued a policy of active engagement in Italy, allying with the Holy Roman Emperor Louis II against the Arabs. In 871, with Byzantine naval support, Louis II captured Bari from the Arabs. The city eventually came under direct Byzantine control in 876, marking a major success for Basil’s western strategy. Basil also sent a fleet of 139 ships to clear the Adriatic of Arab raiders, demonstrating the empire’s renewed naval strength and commitment to protecting its western provinces.

The struggle for southern Italy was not without setbacks. Basil’s position on Sicily deteriorated rapidly, and his attempt to relieve the Arab blockade of Syracuse in 868 ended in defeat. The diversion of a relief fleet to transport marble for church construction, rather than to aid Syracuse, is often cited as a critical error. As a result, Malta fell to the Arabs in 870, and Syracuse was stormed in 878, marking the effective loss of Byzantine Sicily. Despite this, Basil’s forces achieved notable successes elsewhere in Italy. They relieved the Arab siege of Ragusa in 868 and, under the command of the general Nikephoros Phokas the Elder, captured Taranto and much of Calabria in 880. These victories opened a new period of Byzantine domination in southern Italy and reestablished the empire as a major power in the western Mediterranean.

Alliances and Diplomacy: The Role of Cooperation with Western Powers

Basil’s military campaigns were not conducted in isolation. He understood the value of alliances and diplomacy in achieving his strategic objectives. His cooperation with Louis II of the Holy Roman Empire was a prime example of this approach. The alliance was mutually beneficial: the Byzantines provided naval support, while the Western Empire contributed ground troops, compensating for the Byzantines’ relative lack of manpower in Italy. This partnership was instrumental in the capture of Bari and the suppression of Arab piracy in the Adriatic.

Basil’s diplomatic efforts extended beyond military alliances. He worked to mend fences with the papacy, despite tensions arising from the autonomy of the Bulgarian Church and other ecclesiastical disputes. These efforts, while not always successful, helped to stabilize the empire’s western frontier and ensure that Byzantine interests were not undermined by internal Christian rivalries.

PAranoia and Death

Basil’s later years saw the empire outwardly stable, but inwardly, the emperor’s personal world was unraveling. In 879, the death of his eldest and favorite son, Constantine, plunged Basil into deep grief. This loss weakened his resolve and perhaps his judgment, as he increasingly focused on securing the succession for his youngest son, Alexander, whom he raised to the rank of co-emperor.

His relationship with his other surviving son, Leo, was strained from the start. Leo, whom Basil suspected of being the biological son of his murdered predecessor Michael III, was disliked by the emperor for his bookishness and perceived weakness. Basil’s distrust was so profound that he occasionally beat Leo, and when rumors of a plot against him surfaced – prompted by informer Theodore Santabarenos – Basil had Leo imprisoned. The public, however, was not indifferent to Leo’s plight. Rioting erupted, and Basil, in a fit of rage, threatened to blind Leo, only to be dissuaded by Patriarch Photios. Leo’s release after three years did little to mend the rift between father and son, and suspicion lingered until the very end.

Toward the close of his life, Basil exhibited signs of declining mental health. Sources from the period describe him as suffering fits of derangement, and his cruelty toward Leo became more pronounced. The emperor’s paranoia was not unfounded: court intrigue was rife, and Basil, who had himself risen through murder, knew the fragility of imperial power. His final days were marked by a sense of isolation and foreboding, with the specter of his own violent ascent haunting his court.

Basil’s death in 886 was as dramatic as any episode from his reign. According to official records, the elderly emperor was on a hunting expedition in Thrace when he was thrown from his horse and impaled on the antlers of a stag. Basil was rescued by an attendant, who cut him free with a knife. The emperor, however, suspected the attendant of attempting to assassinate him and had the man executed shortly before succumbing to his own injuries. Basil died of fever on August 29, 886, the result of wounds sustained in this bizarre accident.

The circumstances of Basil’s death have fueled speculation ever since. Some historians suggest that the hunting accident may have been a cover-up for foul play, possibly orchestrated by those who wished to see Leo on the throne. Indeed, the fact that Leo – rumored to be the son of Michael III, the emperor Basil had murdered – succeeded him adds a layer of irony and poetic justice to the story. One of Leo VI’s first acts as emperor was to exhume Michael III’s body and rebury it with great ceremony in the Imperial Mausoleum, a move widely interpreted as an acknowledgment of his true paternity and a symbolic repudiation of Basil.

The end of Basil’s reign thus encapsulates the contradictions of his rule. He was a man of humble origins who rose to the pinnacle of imperial power through ruthlessness and ambition, only to see his legacy overshadowed by suspicion, violence, and a haunting sense of unfinished business. His dynasty would go on to rule Byzantium for over two centuries, but the manner of his passing – whether by accident or design – remains one of the most intriguing mysteries of Byzantine history. In death, as in life, Basil I was a figure of paradox: a builder of empires and a man haunted by the ghosts of his past.