During the first three decades of Charlemagne’s reign, military campaigns dominated his rule, driven by various factors: the need to defend against external threats and internal separatists, a desire for conquest and wealth, and the urge to spread Christianity. His battlefield prowess earned him a reputation as a warrior king, elevating the Franks into a formidable European power.

Dealing with the Saxons

Charlemagne’s initial campaign as king of the Franks was spent on the eastern frontier in his first war against the Saxons (782CE), who had been engaging in border raids on the Frankish kingdom. In a short and successful campaign, he defeated the Saxons and seized much treasure. This success helped secure Charlemagne’s reputation among the Frankish nobility and funded further military action, but this campaign was merely the beginning of over thirty years of nearly continuous warfare against the Saxons.

This prolonged struggle, which eventually resulted in the Franks annexing a large territory between the Rhine and the Elbe rivers, was marked by years of raids, broken truces, hostage-taking, mass killings, deportations of rebellious Saxons, harsh measures to enforce Christianity, and occasional Frankish defeats.

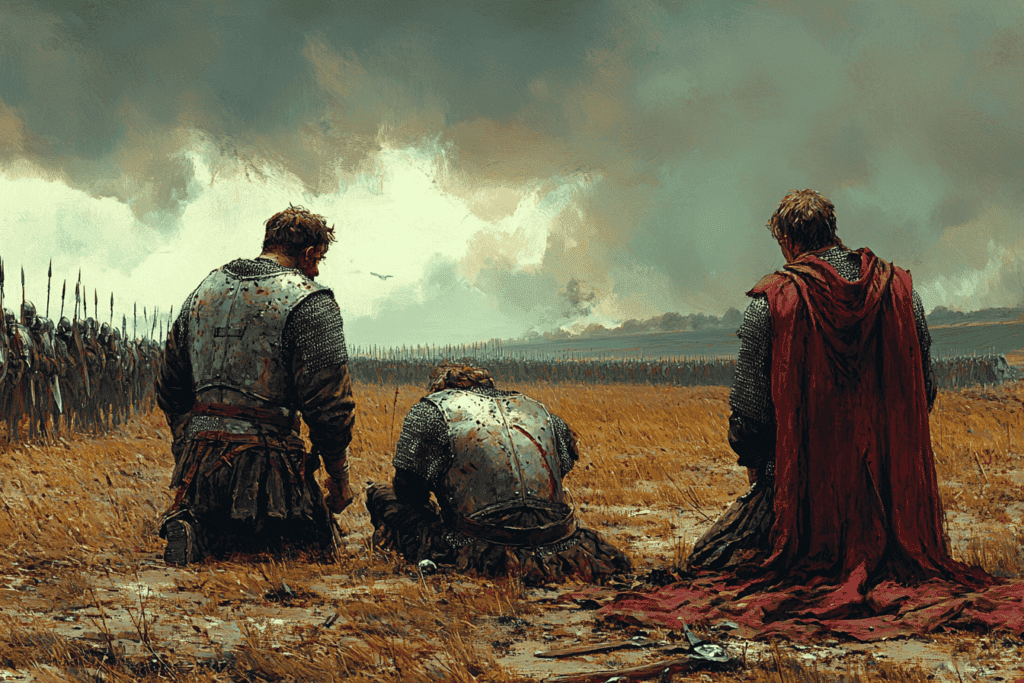

The year 782 saw a major rebellion by the Saxons – and the Frankish response is regarded as the biggest stain on Charlemagne’s legacy. The Saxon rebels, led by Widukind, was initially successful: defeating a Frankish force at the battle of Süntel, before Charlemagne arrived and put down the rebellion. The Saxons surrendered and Charlemagne ordered the execution of 4,500 rebels – who were beheaded in a single bloody day near the confluence of the Aller and the Weser, in what is now Verden. The rebel leader Widukind was not amongst the victims of what became known as the Massacre of Verden since he had fled to Nordmannia [Denmark].

Italy, Spain and Bavaria

While the Saxon conquest was ongoing, Charlemagne launched other campaigns. In 773–774, he responded to Pope Adrian I’s (772–795) appeals for protection by leading a successful expedition into Italy, culminating in his assumption of the Lombard crown and annexation of northern Italy. During this campaign, Charlemagne went to Rome to reaffirm the Frankish protectorate over the papacy and confirm papal rights to territories granted by his father. Additional campaigns were necessary to fully integrate the Lombard kingdom into the Frankish realm, a key step being in 781 when Charlemagne created a subkingdom of Italy with his son Pippin as king.

Concerned with defending southern Gaul from Muslim attacks and lured by promises of support from local Muslim leaders in northern Spain seeking to escape the Umayyad ruler of Cordoba, Charlemagne invaded Spain in 778. This ill-fated venture ended in a disastrous defeat for the retreating Frankish army by Gascon (Basque) forces, later immortalized in the epic poem The Song of Roland. Despite this setback, Charlemagne continued efforts to secure the Spanish frontier. In 781, he created a subkingdom of Aquitaine with his son Louis as king, from which Frankish forces launched campaigns that eventually established control over the Spanish March, the territory between the Pyrenees and the Ebro River.

In 787–788, Charlemagne forcibly annexed Bavaria, whose leaders had long resisted Frankish dominance. This victory brought the Franks into direct conflict with the Avars, Asiatic nomads who had formed a vast empire in the 6th and 7th centuries, inhabited mainly by conquered Slavs on both sides of the Danube. By the 8th century, Avar power was waning, and successful Frankish campaigns in 791, 795, and 796 accelerated the empire’s collapse. Charlemagne seized a significant amount of booty, claimed territory south of the Danube in Carinthia and Pannonia, and initiated missionary work leading to the conversion of the Avars and their former Slavic subjects to Christianity.

Diplomatic success

Charlemagne’s military successes resulted in an ever-expanding frontier that required defense. Through a mix of military force and diplomacy, he established relatively stable relations with various potential adversaries, including the Danish kingdom, several Slavic tribes along the eastern frontier from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans, the Lombard duchy of Benevento in southern Italy, the Muslims in Spain, and the Gascons and Bretons in Gaul.

The situation in Italy was complicated by the Papal States, whose boundaries were problematic, and the pope, who had no clearly defined political status relative to his Frankish protector, now his neighbor as king of the Lombards. Generally, Charlemagne’s relations with the papacy, particularly with Pope Adrian I, were positive, garnering him support for his religious program and praise for his Christian leadership. The increased Frankish presence in Italy and the Balkans intensified diplomatic interactions with the Eastern emperors, strengthening the Frankish position against the Eastern Roman Empire, which was weakened by internal strife and threatened by Muslim and Bulgar pressures on its eastern and northern frontiers. Charlemagne also established friendly relations with the ʿAbbāsid caliph in Baghdad (Hārūn al-Rashīd), the Anglo-Saxon kings of Mercia and Northumbria, and the ruler of the Christian kingdom of Asturias in northwestern Spain. He also held a vague role as protector of the Christian establishment in Jerusalem.

By combining the traditional role of warrior king with aggressive diplomacy and a keen understanding of contemporary political realities, Charlemagne elevated the Frankish kingdom to a leading position in the European world.