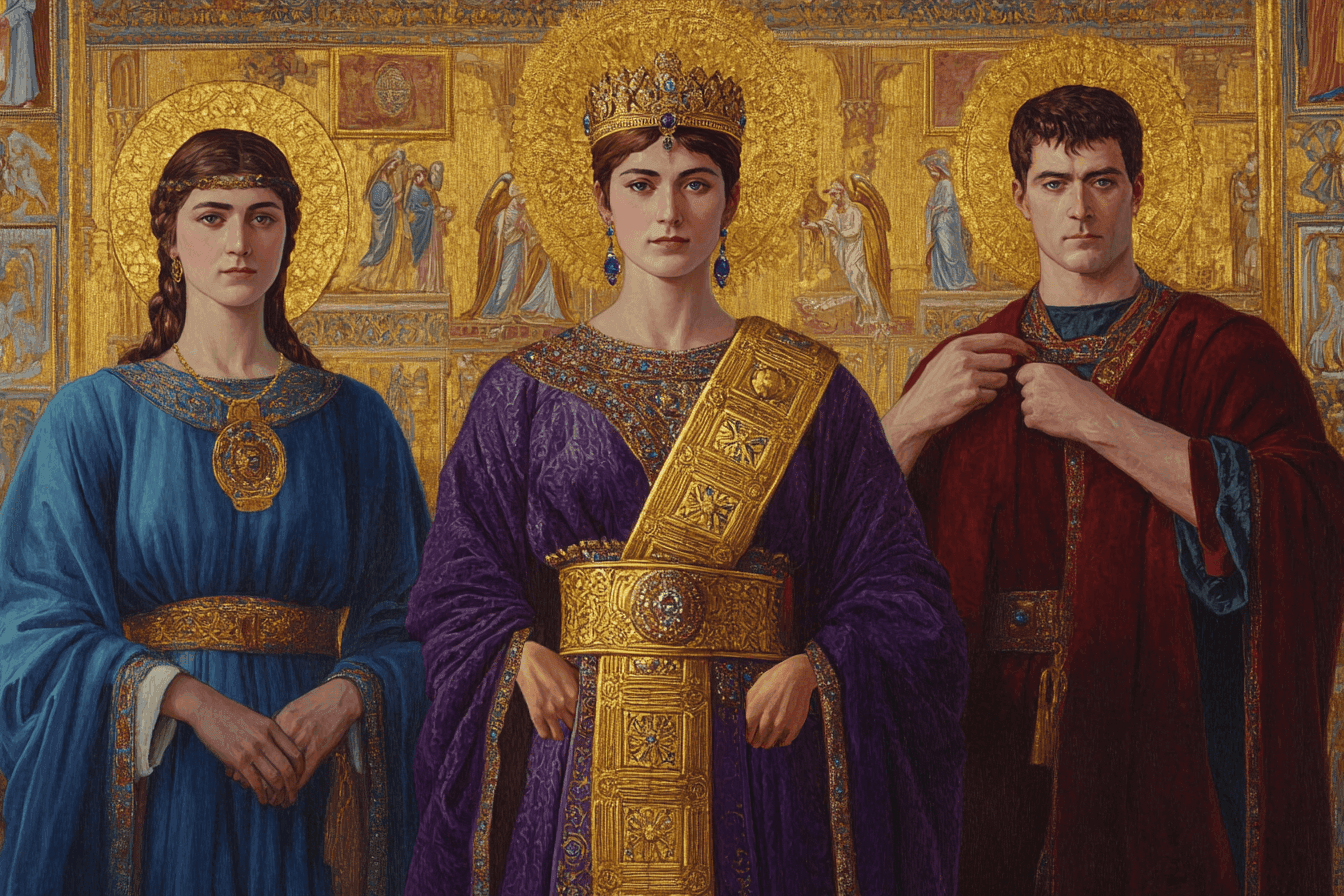

For over two decades, Zoë Porphyrogenita wielded power through strategic marriages, court intrigue, and an unshakable claim to dynastic legitimacy. Her life epitomized the political theater of 11th-century Constantinople. Alongside her sister Theodora, Zoë became one of only four women to rule the Byzantine Empire in her own name.

Born into the Purple: Dynastic Destiny

Zoë’s title Porphyrogenita (“born in the purple”) signaled her birth in the porphyry-lined chamber reserved for children of reigning emperors. As the daughter of Emperor Constantine VIII and niece of Basil II, the “Bulgar-Slayer,” Zoë inherited a realm stretching from Italy to Armenia. Yet her path to power was fraught with uncertainty: Basil II, fearing challenges to his authority, refused to let Zoë or Theodora marry during his lifetime, leaving the dynasty’s future precarious.

When Basil died childless in 1025, Constantine VIII inherited the throne. By then, Zoë was in her late 40s—an age considered ancient for marriage in Byzantium. Her father, desperate to secure the succession, arranged her union with Romanos III Argyros, a wealthy bureaucrat 30 years her senior. The marriage on November 12, 1028, lasted mere days before Constantine’s death, catapulting Zoë into the role of empress consort.

Romanos III (1028–1034): A Marriage of Convenience

Romanos III proved an unpopular ruler, alienating the military and squandering funds on vanity projects like monasteries. His tax reforms sparked unrest, while his military campaigns against Aleppo ended in humiliation. Privately, the marriage soured; Zoë, then in her 50s and desperate for an heir, consulted sorcerers and physicians, but no child came. Romanos openly favored his mistress, while Zoë took a lover—Michael, a low-born but charismatic court chamberlain.

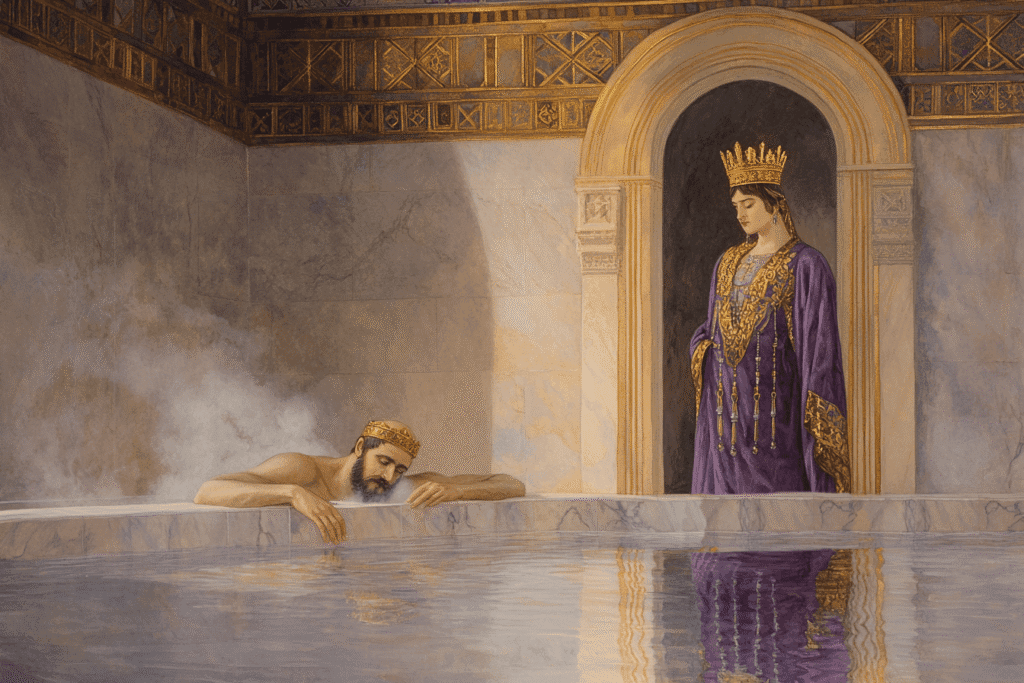

Regicide and Scandal

On April 11, 1034, Romanos was found drowned in his bath—a death officially deemed accidental but widely attributed to Zoë and Michael. Psellus, the contemporary historian, implied her direct involvement: “She had long desired to be rid of him… and now saw her chance”. Within hours, Zoë married Michael, securing his coronation as Michael IV.

Michael IV (1034–1041): The Lover-Turned-Emperor

Zoë married Michael days after Romanos’ death, elevating him to co-emperor. Michael IV, though epileptic and guilt-ridden, initially indulged Zoë’s whims. However, his brother John the Orphanotrophos, the empire’s de facto administrator, sidelined her from power. Zoë’s confinement to the palace gynaeceum marked a stark reversal and she became a prisoner in all but name.

Michael’s health deteriorated, but Zoë’s attempts to reassert influence were thwarted. By 1041, facing rebellion and illness, Michael adopted his nephew Michael V, bypassing Zoë entirely. His death later that year left Zoë vulnerable to her adopted son’s machinations.

From Caulker’s Son to Caesar

Born around 1015 to Stephen, a ship caulker turned disgraced admiral, and Maria, sister of Emperor Michael IV, Michael V owed his ascent to the machinations of his uncle John the Orphanotrophos. Despite Michael IV’s preference for another nephew, John and Empress Zoe pushed the young Michael as heir. In 1035, he was adopted by Zoe and granted the title kaisar (caesar), positioning him as successor. When Michael IV died in December 1041, Michael V was crowned emperor, inheriting an empire strained by financial woes and Norman incursions in Italy.

Michael V (1041–1042): The Nephew’s Betrayal

Determined to rule autonomously, Michael V immediately exiled his uncle John, reversing many of his policies. He recalled exiled nobles, including the future patriarch Michael Keroularios, and reinstated general George Maniakes to counter Norman threats in southern Italy. These moves, however, failed to stabilize his rule. Michael’s fatal miscalculation came in April 1042, when he accused Zoe—his adoptive mother and co-ruler—of plotting to poison him. Under cover of night, he exiled her to the island of Principo, declaring himself sole emperor.

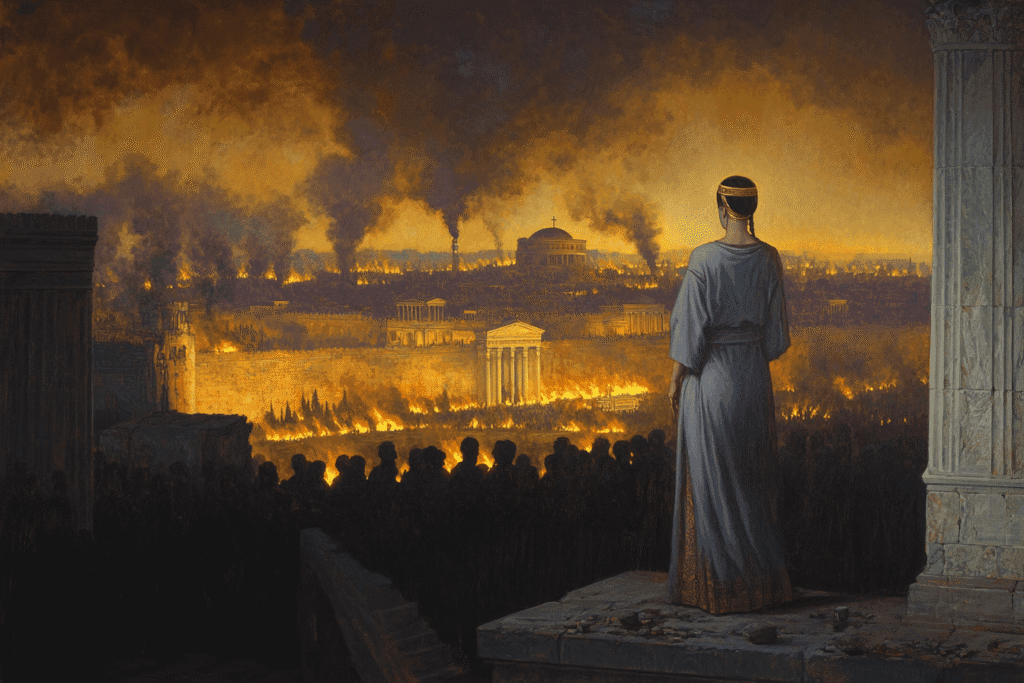

The public backlash was swift and brutal. By dawn, mobs surrounded the Great Palace, demanding Zoe’s restoration. When she was paraded before the crowds in a nun’s habit, the sight further enraged the populace.

The revolt escalated into full-scale urban warfare, with attackers breaching the palace gates and looting treasures. It was among Constantinople’s most destructive uprisings. For three days, the city became a battleground, with fires raging near the Hippodrome and corpses littering the streets. The mob’s specific targeting of tax records reflected widespread resentment over Michael IV’s heavy levies, which his nephew failed to mitigate. This eruption of popular will demonstrated that even an emperor’s divine mandate could be shattered by the collective anger of his subjects.

Downfall and Mutilation

As chaos engulfed Constantinople, Zoe’s sister Theodora was dragged from her convent and crowned co-empress. The siblings’ joint rule marked the first time women led Byzantium without male oversight.

Meanwhile, Michael V fled to the Monastery of Stoudion, where he took monastic vows in a bid for sanctuary. His efforts proved futile: Harald Hardrada, future king of Norway and then-chief of the Varangian Guard, arrested him. Blinded and castrated—a traditional punishment for deposed emperors—Michael died in monastic exile later that year.

The Sister Emperors: Zoë and Theodora (April–June 1042)

The joint reign of Zoë and Theodora was unprecedented. While Zoë charmed crowds with her beauty and generosity, Theodora, austere and pragmatic, handled administration. Together, they:

- Abolished corrupt practices, including the sale of judicial offices.

- Pardoned political exiles and restored confiscated properties.

- Crushed Michael V’s rebellion, ordering his blinding and exile.

Yet tensions simmered. Zoë, resentful of Theodora’s competence, sought a third husband to reassert control. Theodora, wary of Zoë’s impulsiveness, resisted. “The empire is not a woman’s dowry,” she reportedly snapped.

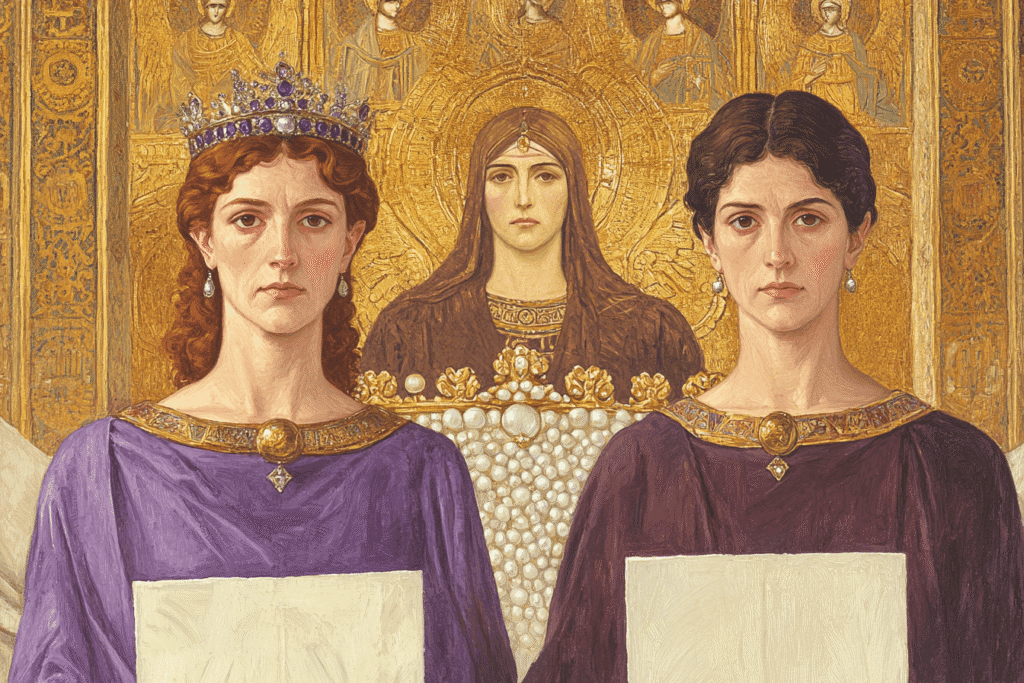

Constantine IX (1042–1050): The Final Marriage

Zoë’s choice for her third husband was Constantine IX Monomachos, a man she had admired during earlier years but who had been exiled by her previous husband Michael IV on charges of treason. Constantine was recalled from Lesbos in 1042 after seven years of banishment and married Zoë on June 11. At the time, Zoë was 64 years old while Constantine was about 42—a significant age gap that underscored the strategic nature of their union.

Their marriage faced immediate opposition from ecclesiastical authorities due to Byzantine laws limiting remarriage. Third marriages were considered contrary to both Roman law and church doctrine, with Patriarch Alexios reluctantly officiating under pressure from imperial authority. Despite these challenges, Constantine was crowned emperor alongside Zoë the day after their wedding.

A Scandalous Court

The reign of Zoë and Constantine IX was marked by scandalous domestic arrangements that shocked Byzantine society. Constantine brought his long-time mistress Maria Skleraina to court, insisting on publicly sharing his life with her despite being married to Zoë. Maria was granted official recognition and treated with great favor, receiving titles and privileges that rivaled those of the empress herself.

Surprisingly, Zoë tolerated this arrangement, perhaps due to her waning interest in romantic entanglements or her pragmatic approach to maintaining power. Increasingly Zoe spent her days in her laboratories concocting perfumes and poisons. However, public outrage over Maria’s presence at court nearly led to a revolt in 1044. The crisis was resolved only when Maria died suddenly from pulmonary disease—a turn of events that quelled unrest but left a stain on Constantine’s reputation.

Political Dynamics

Zoë’s marriage to Constantine IX represented a shift in Byzantine governance. While she retained her status as empress and wielded considerable influence, Constantine assumed significant administrative powers. His reign saw efforts to reform imperial policies alongside continued military decline—a trend that had begun during Zoë’s earlier marriages.

Constantine IX focused on cultural patronage and intellectual pursuits rather than strengthening the empire’s defenses or addressing its economic challenges. His lavish spending on artistic projects led to financial strain but enriched Constantinople’s cultural legacy. Meanwhile, incursions by Seljuk Turks into eastern Anatolia highlighted the empire’s weakening military position.

Zoë died in 1050, leaving Constantine IX and her sister Theodora as co-rulers. When Constantine died in 1055, Theodora ruled alone—the last Macedonian emperor. Her death in 1056 ended a dynasty that had ruled for 189 years.

Zoë’s Paradox: Frivolity and Power

In a world that saw women as mere vessels for dynastic continuity, she became power itself: capricious, enduring, and unforgettable. Her three marriages—each to a man raised to the throne solely by virtue of their union—defined her 22-year reign and underscored the precarious balance of power, ambition, and dynastic survival in 11th-century Byzantium. Zoe successfully ensured her Macedonian dynasty’s survival in her lifetime as she outmaneuvered rivals through marriages and popular support.A cultural icon of her time, her perfumes and piety (she owned a revered icon of Christ) made her a symbol of Byzantine opulence. Yet her extravagance drained the treasury, while her neglect of governance hastened Byzantium’s decline.