In the early 11th century, Scotland was a land of fragmented loyalties and fierce ambitions. Duncan I, a king with grand designs, sought to consolidate his power by bringing the unruly northern regions of Moray, Caithness, and Sutherland under his dominion. His efforts met with mixed success; while Caithness and Sutherland resisted his control, Moray, ruled by his ambitious cousin Macbeth, proved particularly challenging.

Macbeth, a figure shrouded in both historical fact and dramatic fiction, was not merely a nobleman but a mormaer – a title akin to an earl – of Moray. This northern region of Scotland, centered around Inverness, was Macbeth’s inheritance from his father Finlaech. Yet this inheritance came at a bloody cost.

The rise of Macbeth

Finlaech had fallen victim to a brutal murder orchestrated by his nephews Malcolm and GilleComgain. Macbeth’s response was swift and merciless; he avenged his father’s death by setting GilleComgain ablaze in his own manor, thus seizing control of Moray in 1032 CE.

Initially, Macbeth appeared loyal to Duncan I. However, Duncan’s repeated failures on the battlefield soon revealed cracks in his reign. The king’s ill-fated raid on Durham in 1039 CE significantly tarnished his reputation among allies and vassals alike. Meanwhile, Macbeth’s marriage to Gruoch – granddaughter of Kenneth III of Scotland – added another layer of complexity to the political landscape. Gruoch’s previous marriage to GilleComgain had been a source of familial tension, but her union with Macbeth helped quell these disputes. Yet her lineage carried its own historical grievances; Kenneth III had been slain by Duncan’s grandfather Malcolm II in 1005 CE, leaving Gruoch with little affection for Duncan.

Sensing an opportunity amidst Duncan’s waning influence, Macbeth moved decisively. In 1040 CE, Duncan sought to eliminate this potential threat by confronting Macbeth on the battlefield near Pitgaveny. However, it was Duncan who met his end there, paving Macbeth’s path to the throne on August 14th. In the aftermath, Duncan’s sons Malcolm and Donald fled into exile.

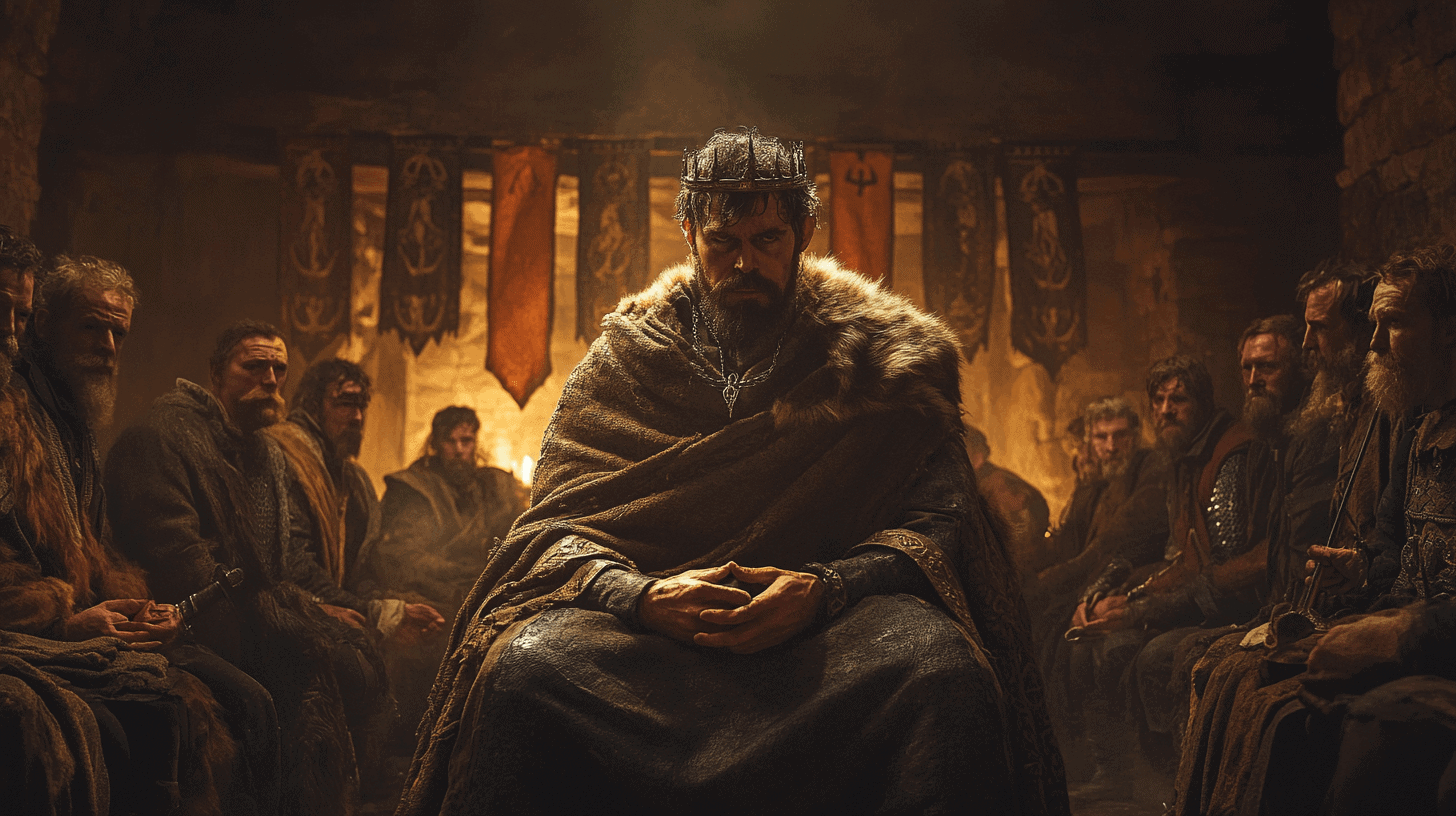

King Macbeth

Macbeth’s reign over Scotland is a subject of sparse historical records and much interpretation. Despite this scarcity of sources, some chronicles suggest that Macbeth governed more effectively than his predecessor. He is credited with fostering prosperity during his rule – an achievement noted even by medieval chroniclers.

Yet challenges persisted. The Viking-controlled territories of Sutherland and Caithness remained a constant threat. Moreover, internal dissent continued to simmer; in 1045 CE, Macbeth faced a rebellion led by Crinán, father of the late Duncan I. The battle at Dunkeld saw Crinán’s demise and reaffirmed Macbeth’s hold on power.

The year 1046 brought new conflicts as Siward, the ambitious earl of Northumbria, launched an incursion into Scottish lands. Siward briefly seized control over regions like Lothian and Strathclyde before being repelled by Macbeth’s counteroffensive from the north. Although Siward viewed this setback as temporary, it underscored the precarious nature of Macbeth’s rule.

Despite these military engagements, Macbeth maintained strong ties with the medieval church—a strategic alliance that bolstered his legitimacy and secured favorable chronicling by monastic scribes. His pilgrimage to Rome in 1050 CE stands as testament to both his piety and confidence in leaving Scotland under capable stewardship during his absence.

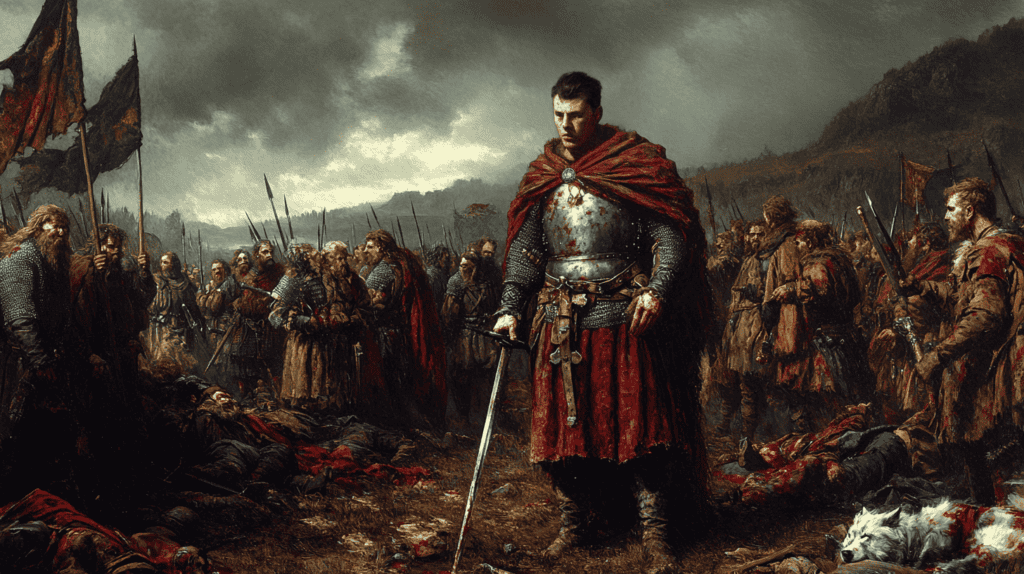

The Battle of Dunsinane

However, threats from the south loomed large as Malcolm Canmore – Duncan I’s son – emerged as a formidable adversary with backing from England’s King Edward the Confessor and Siward. In 1054 CE, an English army invaded Scotland with devastating effect.

The Battle of Dunsinane, fought on July 27, 1054, was a pivotal clash that reshaped the Scottish throne’s fate. This confrontation saw the forces of Macbeth, face off against an invading army led by Siward, Earl of Northumbria, and Malcolm Canmore, the exiled son of King Duncan I. The battle unfolded on the slopes of Dunsinane Hill in Perthshire, a site steeped in both historical and literary significance.

Macbeth’s forces, bolstered by Norman knights who had sought refuge in Scotland, were determined to defend his reign. However, they faced a formidable opponent. Malcolm and Siward’s troops employed cunning tactics, famously advancing under the cover of branches from Birnam Wood—a strategy immortalized by Shakespeare. Despite Macbeth’s valiant defense, his army suffered heavy losses, with 3,000 Scots falling compared to just 1,500 English casualties.

Though Macbeth survived the battle, his power was irrevocably weakened. Siward and Malcolm’s victory allowed them to gain control over key Scottish territories, setting the stage for Malcolm’s eventual ascension as Malcolm III. This battle not only marked a turning point in Scottish history but also cemented its place in cultural memory through Shakespeare’s dramatic retelling.

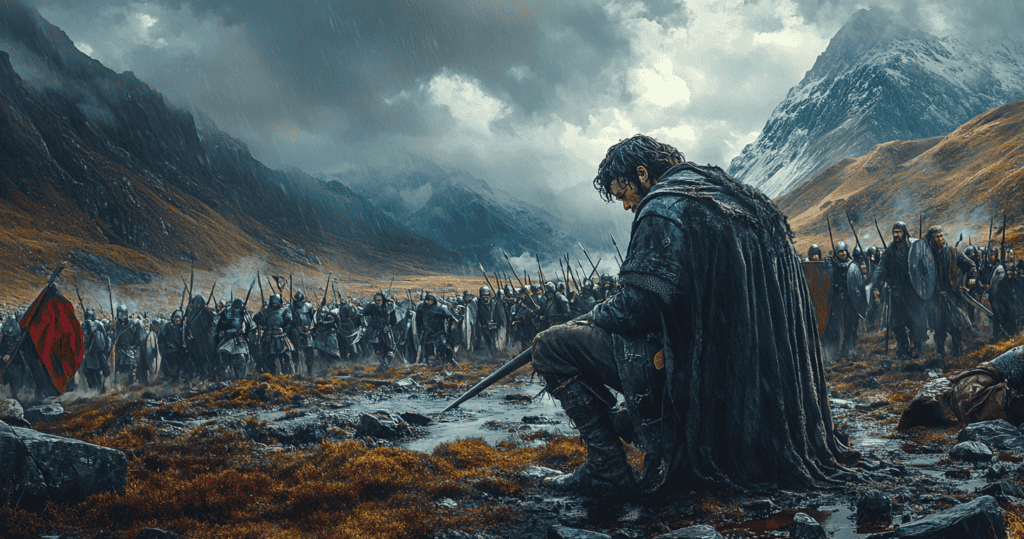

The Battle of Lumphanan

On August 15, 1057, the Battle of Lumphanan unfolded in the rugged landscape of Aberdeenshire, marking the dramatic end of Macbeth’s reign. This pivotal clash was orchestrated by Malcolm Canmore, the son of the slain King Duncan I, who sought to reclaim his father’s throne. Macbeth, known as the King of Alba, was caught off guard by Malcolm’s strategically planned ambush.

As Macbeth and his small band of loyal retainers marched southward, they were suddenly besieged near the Peelring of Lumphanan by a combined Scottish-Viking force led by Malcolm. The battlefield was a chaotic scene where Macbeth’s forces, numbering between 300 and 450 mounted warriors, were vastly outnumbered. Despite their valiant efforts, Macbeth’s men were overwhelmed by Malcolm’s superior numbers and tactical advantage.

In the ensuing melee, Macbeth was either killed in combat or captured and executed shortly thereafter. His death marked an end not only for himself but also for any lingering hopes of maintaining Moray’s independence under his lineage.

Legacy

Following Macbeth’s demise came brief succession by Lulach – his stepson – before Malcolm III ascended as king after orchestrating Lulach’s assassination at Essie in Strathbogie circa 1058 CE. This transition restored Duncan I’s line through Malcolm III whose reign heralded increased Anglo-Saxon influence upon marrying English princess Margaret.

Thus ended one chapter in Scotland’s tumultuous history – a chapter immortalized not only through historical accounts but also through William Shakespeare’s dramatic retelling centuries later – a portrayal that forever etched Macbeth into cultural memory as both tyrant and tragic figure alike.