The Carolingian Empire, once a beacon of power and unity in Western Europe, began its slow but inexorable decline in the latter half of the 9th century. This is the story of how this great empire, founded by Charlemagne, crumbled under the weight of internal strife, external threats, and poor leadership.

The Seeds of Decline

The year is 850 CE. The Carolingian Empire, spanning vast territories across modern-day France, Germany, Italy, and beyond, stands as the most powerful political entity in Western Europe. Yet, beneath its impressive facade, cracks are beginning to show.

Louis the Pious, son of the great Charlemagne, had died in 840, leaving behind a legacy of conflict. His death sparked a three-year civil war among his sons, culminating in the Treaty of Verdun in 843. This treaty divided the empire into three kingdoms: Francia Occidentalis in the west, ruled by Charles the Bald; Francia Orientalis in the east, under Louis the German; and Francia Media, including Italy and Rome, governed by Lothar, who also inherited the imperial title.

This division, while temporarily resolving the fraternal conflict, sowed the seeds for future instability. The concept of a unified empire remained, but the reality on the ground was far different. Each kingdom began to develop its own identity, and the bonds holding them together grew increasingly tenuous.

Viking Invasions and Internal Strife

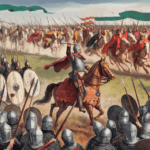

As the 850s progressed, a new threat emerged from the north. Viking raiders, drawn by the wealth of the Carolingian lands, began to strike with increasing frequency and ferocity. Their longships, capable of navigating both open seas and inland waterways, allowed them to penetrate deep into Carolingian territory.

In 856, a group of Vikings sailed up the Seine, reaching Paris itself. The city, once the pride of the Frankish kingdoms, was sacked. Charles the Bald, ruler of West Francia, proved unable to mount an effective defense. Instead, he resorted to paying the Vikings to leave – a short-term solution that only encouraged further raids.

Meanwhile, the Carolingian rulers continued to squabble among themselves. In 858, Louis the German invaded Charles the Bald’s territory, attempting to seize control of West Francia. Though this attempt ultimately failed, it further weakened the already strained bonds between the Carolingian kingdoms.

The Decay of Imperial Infrastructure

As the 860s dawned, the empire faced not only external threats and internal conflicts but also a slow decay of its very foundations. The vast network of roads and bridges, essential for communication and trade, began to crumble. The manufacturing base, never strong to begin with, weakened further.

The monetary system, once a symbol of Carolingian power and unity, began to fragment. Gold coins, once minted in abundance, became increasingly rare. By the end of the decade, no Carolingian gold was circulating, replaced by a patchwork of local silver coinages – a clear sign of the erosion of central authority.

The Rise of Local Powers

As imperial power waned, local nobles began to assert their independence. Counts, dukes, and margraves, originally appointed as representatives of the emperor, increasingly treated their offices as personal possessions. They demanded land in exchange for their support in the endless civil conflicts, further depleting the royal domains.

When the Carolingian monarchs ran out of land to give, these nobles turned to the lands of churches and monasteries. The central government, weak and distracted, could no longer protect these institutions. This not only weakened the economic base of the empire but also strained its relationship with the Church, long a pillar of Carolingian power.

The Brief Resurgence and Final Decline

In 881, a glimmer of hope appeared. Charles the Fat, youngest son of Louis the German, was crowned emperor. Through a series of fortuitous deaths and political manoeuvres, he managed to reunite most of Charlemagne’s empire under his rule by 884.

However, this reunification proved short-lived. Charles the Fat, suffering from what historians believe may have been epilepsy, proved incapable of defending the empire against continued Viking raids. In 886, he infamously paid off Vikings besieging Paris rather than fighting them, earning him a reputation for cowardice and incompetence.

The following year, 887, saw the final unraveling of Carolingian power. Arnulf of Carinthia, an illegitimate nephew of Charles the Fat, raised the standard of rebellion. Instead of fighting, Charles fled to Neidingen, where he died in 888.

The Aftermath

With Charles the Fat’s death, the Carolingian Empire fractured irreparably. Local nobles, no longer bound by even the pretense of imperial authority, elected their own kings. In East Francia, Arnulf of Carinthia took the throne. In West Francia, Odo, Count of Paris, was elected king, though he would eventually be replaced by a Carolingian, Charles the Simple, in 898.

The next two decades saw a rapid decentralization of power. The idea of a unified empire faded, replaced by a patchwork of kingdoms and duchies. In many areas, real power devolved to the local level, with counts and dukes exercising near-independent authority.

The Last Gasp

As the 10th century dawned, Carolingian rule persisted in name in some areas, but its power was a mere shadow of its former glory. In East Francia, the Carolingian line ended in 911 with the death of Louis the Child. In West Francia, Carolingian kings continued to rule intermittently until 987, but their authority rarely extended beyond the immediate vicinity of their capital.

The Viking threat, which had played such a significant role in weakening the empire, began to transform. In 911, the Viking leader Rollo was granted the territory that would become Normandy, in exchange for his allegiance to the West Frankish king. This marked the beginning of the Vikings’ integration into the post-Carolingian political landscape.

By 911, the Carolingian Empire, which had once dominated Western Europe, was no more. In its place stood a collection of successor kingdoms, each grappling with the challenges of a new era. The dream of a unified Christian empire, so vividly realized by Charlemagne, had faded into history.