Galla Placidia’s life reads like an epic: born into the highest echelons of Roman power, she would endure abduction, widowhood, political intrigue, and ultimately rule as regent over a crumbling Western Empire. Amid one of history’s most turbulent eras she journeyed from imperial hostage to queen and empress regent.

Imperial Origins and Early Upheaval

Galla Placidia was born around 390–393 CE, the daughter of the Roman emperor Theodosius I, one of the last rulers to preside over a united Roman Empire. Her mother, Galla, was herself the daughter of a Western emperor, Valentinian I, making Placidia a scion of both Eastern and Western imperial lines. Raised in the palaces of Constantinople and Milan, she was surrounded by the trappings of power but also by the growing instability that marked the late Roman world.

The death of her father in 395 split the empire between her two half-brothers: Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West. The Western Empire, plagued by internal strife and external threats, soon became the epicenter of crisis. By the early 5th century, waves of barbarian invasions battered the Roman frontiers, and the imperial court, now based in Ravenna, struggled to maintain control.

The Cataclysm: Sack of Rome and Captivity

In 410, the unthinkable happened: Rome, the “eternal city,” fell to the Visigoths under King Alaric. For the first time in nearly 800 years, the city was sacked by a foreign army. Amid the chaos, Galla Placidia, then in her late teens or early twenties, was taken captive by the Visigoths. Her brother Honorius, emperor of the West, refused to ransom her, leaving her fate in the hands of her captors.

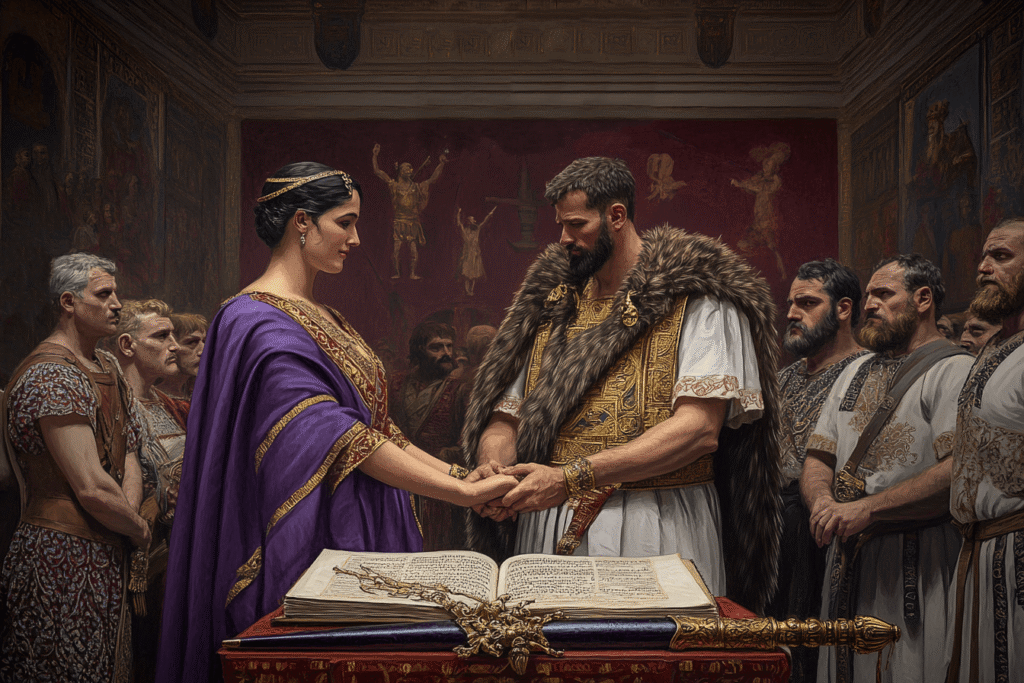

Placidia’s years among the Goths were formative. She was not merely a hostage; she became a bargaining chip in the complex negotiations between the Goths and the Roman state. When Alaric died soon after the sack, his brother-in-law Ataulf succeeded him as king. In a move that shocked both Romans and Goths, Ataulf married Galla Placidia in 414, elevating her to queen of the Visigoths. Their marriage, celebrated in Narbonne, was both a personal union and a political alliance, symbolizing – at least briefly – a hope for reconciliation between Roman and barbarian worlds.

Queen Among the Visigoths

As queen, Placidia lived with Ataulf in southern Gaul and later in Barcelona, where she gave birth to a son, Theodosius. The infant’s death soon after birth was a personal tragedy and a political blow, as he represented a potential union of Roman and Gothic dynasties. The couple’s hopes for a lasting alliance were dashed when Ataulf was assassinated in 415, plunging the Visigoths into further turmoil.

Placidia’s status shifted once again. The new Gothic leadership, eager to restore relations with Rome, returned her to the imperial court in exchange for food supplies and political concessions. Thus ended her extraordinary sojourn among the Visigoths, but her wild ride was far from over.

Back to Rome: Forced Marriage and Political Ascent

Upon her return, Placidia found herself at the mercy of her brother Honorius, who now saw her as a valuable asset. He compelled her to marry his most trusted general, Constantius, in 417. Though the union was political, Placidia played her part, bearing two children: Justa Grata Honoria and a son, Valentinian. Constantius was elevated to co-emperor in 421, making Placidia Augusta, or empress consort.

Constantius’s sudden death later that year left Placidia a widow once more – but now, she was a widow with imperial children and a claim to power. Tensions with Honorius forced her into exile in Constantinople, where she sought support from her nephew, Theodosius II, the Eastern emperor. But Placidia was no passive victim; her fortunes would soon rise again with the death of Honorius in 423, which plunged the Western Empire into a succession crisis.

Regent of a Crumbling Empire

With Honorius dead and a usurper, John, seizing the Western throne, Placidia and her young son Valentinian became the focus of imperial legitimacy. Backed by Eastern Roman troops, Placidia returned to Italy in 425. The usurper was overthrown, and six-year-old Valentinian III was proclaimed emperor, with Placidia as regent.

Placidia’s regency (425–437) was marked by both achievement and adversity. She navigated a treacherous political landscape, balancing powerful generals, ambitious courtiers, and the ever-present threat of barbarian invasions. Her early supporters, such as Bonifacius and Felix, were gradually sidelined or eliminated, while the formidable general Flavius Aetius rose to dominate military and political affairs.

Placidia’s earlier experiences as a captive and later queen among the Visigoths gave her unique diplomatic skills, but the sheer scale of the barbarian incursions and the empire’s military weakness limited her ability to respond effectively. Despite her efforts, the Western Empire continued to unravel. The Visigoths and other barbarian groups carved out independent kingdoms in Spain and Gaul. Africa, the empire’s breadbasket, slipped from Roman control. The Vandals captured Carthage in 439, severing a vital source of grain and revenue. Placidia’s authority waned as Aetius assumed effective control of the army and imperial policy, but she remained an influential figure at court until her death in 450.

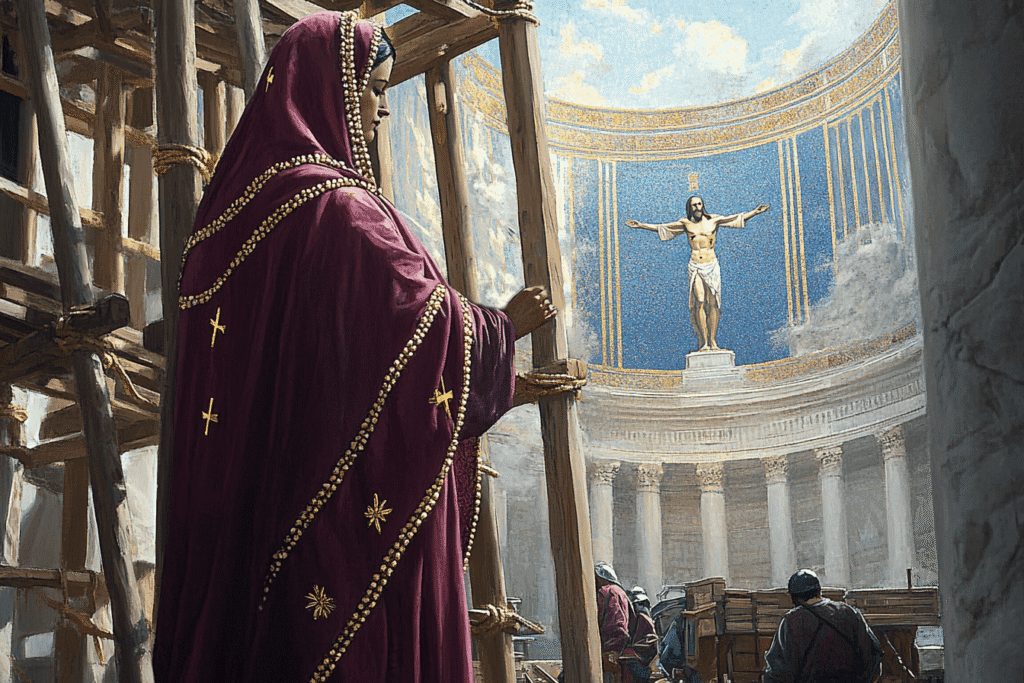

A Christian Empress and Builder

Placidia was not only a political operator but also a devout Christian and patron of the Church. Her reign saw the construction and restoration of important churches, including the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. In Ravenna, she built San Giovanni Evangelista in gratitude for surviving a perilous sea voyage. The building known as the “Mausoleum of Galla Placidia,” now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, stands as a testament to her legacy in art and architecture, though it was never her actual tomb.

She cultivated relationships with leading churchmen, such as Bishop Peter Chrysologus, and played a key role in the Christianization of the Western Empire. Her piety and public works helped reinforce the legitimacy of her regency and the dynasty she sought to preserve.

Family Intrigue and the Shadow of Attila

If Placidia’s own life was a saga of captivity and power, her daughter Honoria’s story nearly brought the entire empire to its knees. In the spring of 450, Honoria, desperate to escape an unwanted marriage to a Roman senator, sent a plea for help to the most feared man in Europe: Attila the Hun. To make her appeal convincing, she included her engagement ring – a gesture Attila interpreted as a marriage proposal.

Attila’s response was explosive. He demanded Honoria’s hand and half the Western Roman Empire as her dowry. The Western Emperor, Placidia’s son Valentinian III, was furious and considered executing his own sister for treason. Only Placidia’s intervention saved Honoria’s life, though she was forced into a different loveless marriage to contain the scandal.

Attila, undeterred, used the incident as a pretext for his devastating invasion of the Western Empire. The Huns rampaged through Gaul and Italy, culminating in the legendary Battle of the Catalaunian Plains. Placidia did not live to see Attila’s final defeat, but the crisis her daughter sparked underscored the precariousness of the empire – and the enduring influence of Placidia herself, who had once again averted a family catastrophe that might have doomed Rome entirely. Placidia died in Rome in November 450 at the age of 58.

Legacy: A Last Great Roman Empress

Galla Placidia’s life was a microcosm of the late Roman world- its grandeur, its chaos, its capacity for both destruction and renewal. She was a survivor, a negotiator, and a builder, who navigated the shifting tides of fortune with remarkable tenacity. From imperial daughter to captive queen, from empress consort to regent, her wild ride to power was as improbable as it was extraordinary.

Her regency marked one of the last periods of effective, if embattled, rule in the Western Roman Empire. Though she could not halt the empire’s decline, her efforts to maintain stability, foster Christian piety, and preserve her son’s throne left an indelible mark on the twilight of Roman rule.