The Rashtrakuta dynasty emerged as a dominant force in 8th-century India, rising to power in 756 CE and shaping the Deccan region’s history and culture for over two centuries. What began as a feudal rule evolved into one of South Asia’s greatest empires, influencing politics, art, literature, and society from the heart of the Indian subcontinent.

Origins and Ascent

The rise of the Rashtrakutas is closely tied to Dantidurga, who from his seat at Achalapura (now Ellichpur, Maharashtra), challenged the prevailing Chalukya power. By defeating Kirtivarman II of Badami in 753 AD, Dantidurga ended the main branch of Chalukya rule, marking the beginning of Rashtrakuta ascendancy in the Deccan. This huge victory was not only military but also symbolic, as Dantidurga performed the Hiranyagarbha ritual to legitimize his rule.

Before his final conquest, Dantidurga skillfully navigated Deccan politics, defeating the kings of Kalinga and Kosala, subduing Malwa’s Gurjaras, and forging alliances with the Pallavas through marriage. These moves strengthened his position and laid the foundation for one of India’s most impressive royal dynasties.

Consolidation and Expansion

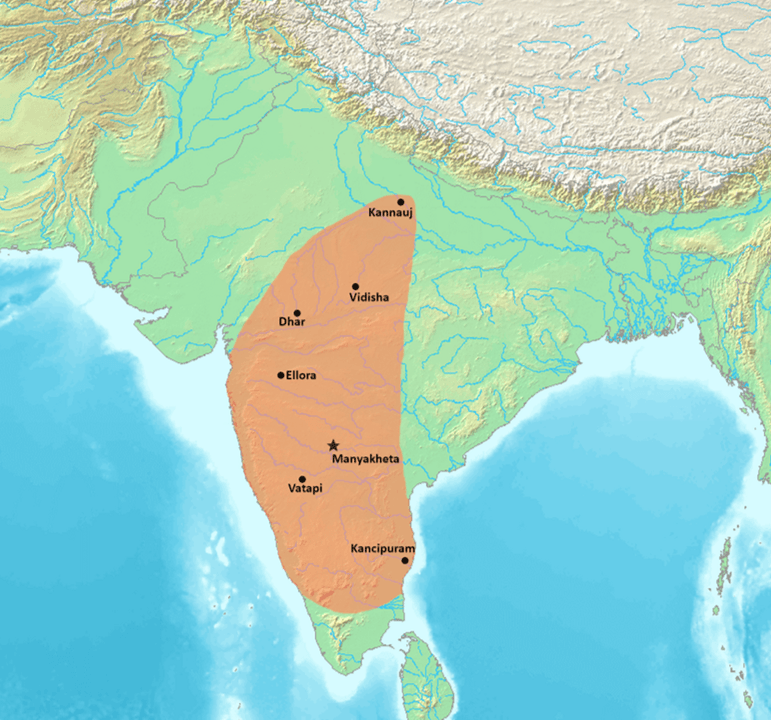

Following Dantidurga’s death, his successor Krishna I rapidly expanded Rashtrakuta control into present-day Karnataka and the Konkan coast. The dynasty’s heartland encompassed all of modern Karnataka, Maharashtra, and parts of Andhra Pradesh, representing a fusion of Dravidian and northern Deccan cultures.

Notably, Krishna I is credited with constructing the magnificent rock-cut Kailasa temple at Ellora, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a testament to the dynasty’s artistic ambition and technical prowess. This monument symbolized not just religious devotion, but also the Rashtrakutas’ support of learning, architectural innovation, and multicultural patronage.

The Age of Imperial Karnataka

Under Dhruva Dharavarsha (ruled 780–793), the Rashtrakutas expanded northward, subjugating rivals in central India, as well as the Gangas of Talakad and Eastern Chalukyas. He led raids into Kannauj, the northern seat of power, where he successfully contested Pratihara and Pala dynasties in the so-called tripartite struggle for supremacy in North India.

Dhruva’s campaigns gained not just territory but prestige, establishing the Rashtrakuta empire as “King of kings” – a pan-Indian power recognized by contemporary travelers like Al-Masudi and Ibn Khordadba, who wrote of their might, influence, and wealth. The Rashtrakuta king, often called Rajadhiraja, became one of the four great rulers of the world, standing alongside the caliph in the Middle East and the emperors of Byzantium and China.

Governance and Cultural Vibrancy

The Rashtrakutas’ rule wasn’t just political; it was also cultural. They embraced both Sanskrit and Kannada, encouraging writers and poets in both languages and contributing to the earliest forms of Kannada literature. Court poets flourished, producing works like the Kavirajamarga, the earliest known Kannada poem, authored by King Amoghavarsha I.

The dynasty’s rulers, while Kannadigas, also conversed in northern Deccan dialects, fostering an environment of linguistic and cultural syncretism. Their encouragement of art and literature left deep marks on Indian tradition, influencing styles and themes for generations.

Architecture and Art

Several Rashtrakuta monarchs were devoted patrons of art, especially Krishna I, whose architectural achievements at Ellora remain legendary. The monumental rock-cut temples, designed to resemble chariots and celestial abodes, voiced the dynasty’s spiritual philosophy and their administrative reach.

The Rashtrakuta Legacy

The Rashtrakuta legacy extended long after their rule, with various offshoots and related kingdoms, such as the Rashtrakutas of Gujarat, Saundatti, and Rajasthan, perpetuating their influence into later centuries. Even after their political decline, their contributions endured in literary, religious, and architectural traditions across the subcontinent.

The Rashtrakutas were highly regarded by contemporary Arab travelers, who noted that the kings of India looked toward the Rashtrakuta monarch in prayer, acknowledging his primacy. The empire’s might was recognized from Sindh to Konkan, and even as far as Ceylon (Sri Lanka), where rulers with Rashtrakuta ties rose to power.

Tripartite Struggle and the PAN-India Power

The Rashtrakutas played a central role in the tripartite struggle for control of Kannauj, clashing with the Pratiharas and Palas for dominance of the rich Gangetic plains. Their victories in these campaigns, especially under kings like Dhruva and Govinda III, consolidated their pan-Indian authority – a feat few dynasties managed in medieval India.

Society and Administration

The Rashtrakutas were Dravidian farmers by origin but evolved into sophisticated administrators, developing a feudal system marked by land grants, local autonomy, and religious endowments. Their governance mixed centralization with regional flexibility, maintaining stability while encouraging local productivity and devotion.

While broadly Hindu, the Rashtrakutas supported Jain, Buddhistic, and Shaivite traditions alike. Religious tolerance was manifest not only in their temple-building but also in their patronage of diverse scholarly communities, temples, and monasteries.

Decline and Fragmentation

By the late 10th century, Rashtrakuta authority began to wane. Disasters such as the sack of their capital under Khottiga Amoghavarsha IV marked the start of their decline, eroding imperial confidence and inviting factionalism. The final Rashtrakuta ruler, Indra IV, performed the Jain ritual of Sallekhana, signifying both an end and a spiritual culmination of the dynasty’s journey.

Despite their fall, brave feudatories, including the Ganga and Kadamba chiefs, supported remnant Rashtrakuta lines in the Western Ghats for a time, until the Chalukyas of Taila I claimed succession. Even after their decline, the Rashtrakutas’ cultural and administrative model served as a blueprint for subsequent Deccan and South Indian kingdoms.

Enduring Contributions

The Rashtrakutas’ two-century rule left a legacy visible today in art, architecture, literature, and the social fabric of South India. The rock-cut temples of Ellora, Karnataka’s literary heritage, and the Rashtrakuta diaspora across India are enduring monuments to their greatness.

The ascent of the Rashtrakuta dynasty in 756 AD marks a watershed in Indian history – a story of triumph, innovation, and transformation. From their humble beginnings as feudatories, the Rashtrakutas rose through shrewd alliances, military acumen, and cultural patronage to become “King of kings,” shaping the course of the Deccan and the subcontinent for generations. Their legacy is woven into the temples, texts, and traditions of South Asia, testifying to the enduring allure of imperial Karnataka’s greatest dynasty.