Sigurd I Magnusson holds a unique place in history as the first European king to personally lead a crusade. His remarkable journey from Norway to Jerusalem between 1107 and 1111, known as the Norwegian Crusade, was a defining chapter in his reign and a testament to the enduring legacy of Viking exploration.

The Hardrada Legacy: Sigurd’s Introduction to Kingship

Sigurd was one of the three sons of King Magnus III, the others being Øystein and Olaf – all were the king’s illegitimate sons from different mothers. The three half-brothers co-ruled the kingdom from 1103 to avoid feuds or war. Sigurd ruled alone after Olaf died in 1115 and Øystein in 1123.

Sigurd’s father Magnus, was a warrior-king obsessed with reviving Norway’s Viking Age glory. His campaigns between 1098 and 1103 aimed to secure control over the Orkney Islands, Hebrides, and Irish Sea trade routes, areas where Norwegian influence had waned.

At just eight or nine years old, Sigurd accompanied Magnus on these expeditions, a practice typical of medieval heirs who learned rulership through direct exposure to warfare and diplomacy. Sigurd’s early role was likely symbolic—a prince representing dynastic continuity—but his presence underscored the campaign’s political stakes.

The 1098 Campaign: Subjugating the Isles

In 1098, Magnus launched his first major expedition to the Irish Sea region, assembling a fleet of up to 160 ships (though contemporary accounts vary). Sigurd, still a child, was nominally installed as earl of Orkney—a title stripped from the local Thorfinnsson dynasty—while Magnus asserted direct control. This move neutralized potential rivals and signaled Norway’s intent to dominate the region.

The campaign was a successful mix of diplomacy and violence:

- Orkney and Hebrides: Magnus deposed Earls Paul and Erlend Thorfinnsson, taking their sons hostage and appointing loyalists like Haakon Paulsson as puppet rulers.

- Scottish Coast: Norwegian forces raided Kintyre, Mull, and Islay, leveraging alliances with local chieftains to extract tribute.

- Strategic Targets: Iona, the sacred monastic island, was spared pillaging—a calculated gesture to avoid alienating Christian allies.

- Mann (Isle of Man): Magnus expelled its Norse-Gaelic ruler, Lagman Godredsson, and made Mann a linchpin of Norwegian influence. The king rebuilt forts with timber from Galloway and encouraged Norwegian settlement, aiming to cement control over trade routes linking Dublin to York..

The Welsh Skirmish: A Lesson in Overreach

Magnus’s ambition soon led to overextension. In 1098–1099, he ventured to Anglesey in Wales, ostensibly to aid Gruffudd ap Cynan, a Welsh king exiled to Ireland by Norman invaders. Magnus’s six-ship fleet clashed with Norman forces, resulting in a Norse victory and the death of the Norman Hugh of Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury—an incident immortalized in sagas as a warrior duel.

Though tactically successful, the Welsh campaign strained Norwegian resources. Sigurd witnessed firsthand the risks of distant expeditions: supply lines grew tenuous, and local alliances proved fleeting. This experience likely informed his later crusade logistics, where securing winter bases (e.g., in Sicily) proved critical.

The Irish Dimension: Prelude to Crusading

Magnus’s final campaign in 1102–1103 targeted Ireland, where he sought to install Norwegian proxies. Magnus sought control of Dublin which, as Ireland’s wealthiest port, promised access to silver, slaves, and prestige—resources vital for funding large-scale expeditions.

However, in 1103, Magnus was killed in Ulster, possibly ambushed while foraging. His death left Sigurd and his half-brothers to inherit a kingdom in flux. At just 14, Sigurd returned to Norway to co-rule with his half-brothers Øystein and Olaf, navigating factional disputes while upholding his father’s expansionist policies.

The early years of Sigurd’s reign were marked by stability under joint rule. While Øystein focused on domestic governance and strengthening Norway’s infrastructure, Sigurd’s ambitions turned outward. His decision to embark on a crusade was influenced by both religious fervor and a desire to emulate the exploits of his Viking ancestors.

The Norwegian Crusade Begins (1107)

In 1107, Sigurd launched the Norwegian Crusade with an impressive fleet of 60 ships carrying approximately 5,000 men. Unlike other crusaders who traveled overland through Europe, Sigurd chose a maritime route—a nod to his Viking heritage. His journey began with stops in England before heading south toward the Iberian Peninsula.

Battles in Iberia

Their arrival in Santiago de Compostela, known to the Norwegians as Jakobsland (the Land of St. James), was initially peaceful. The local lord permitted them to winter there, but tensions soon escalated due to a dire food shortage.

As supplies dwindled, the local lord refused to sell provisions to the Norwegians. This act of defiance infuriated Sigurd, who responded with characteristic Viking decisiveness. He rallied his men, attacked the lord’s castle, and seized what they needed through force. The identity of this local noble remains uncertain, but the incident underscored Sigurd’s pragmatic approach to survival and his readiness to assert dominance, even over fellow Christians.

By spring 1109, Sigurd’s fleet resumed its journey south along the Portuguese coast. Their next significant encounter occurred near Sintra (likely modern-day Colares), where they confronted Moorish forces defending a castle. The Moors resisted conversion to Christianity, prompting Sigurd’s men to storm the stronghold. The defenders were killed, and the castle fell into Norwegian hands. This victory was followed by a battle at Lisbon, described as “half Christian and half heathen,” a city straddling the cultural divide between Christian and Muslim Iberia. Here too, Sigurd’s forces triumphed.

Continuing their campaign, the Norwegians sacked Alcácer do Sal (Alkasse), another Moorish-held town further south. They then encountered a Muslim fleet near the Strait of Gibraltar (Norfasund). In a fierce naval engagement, Sigurd’s warriors captured six enemy ships and routed the rest. Among their prisoners were pirates from the Balearic Islands, whose accounts piqued Sigurd’s interest in these infamous strongholds of piracy and slavery.

The Norwegian fleet subsequently turned its attention to the Balearics, launching raids on Formentera, Ibiza, and Menorca. These islands were notorious centers of piracy and the slave trade. Here, they clashed with Saracen forces who had fortified themselves within caves surrounded by stone walls. Employing Viking ingenuity, Sigurd ordered large trees to be set ablaze at the cave entrances, forcing the defenders out or killing them inside. This brutal yet effective strategy secured significant booty for his forces.

Arrival in Jerusalem (1110)

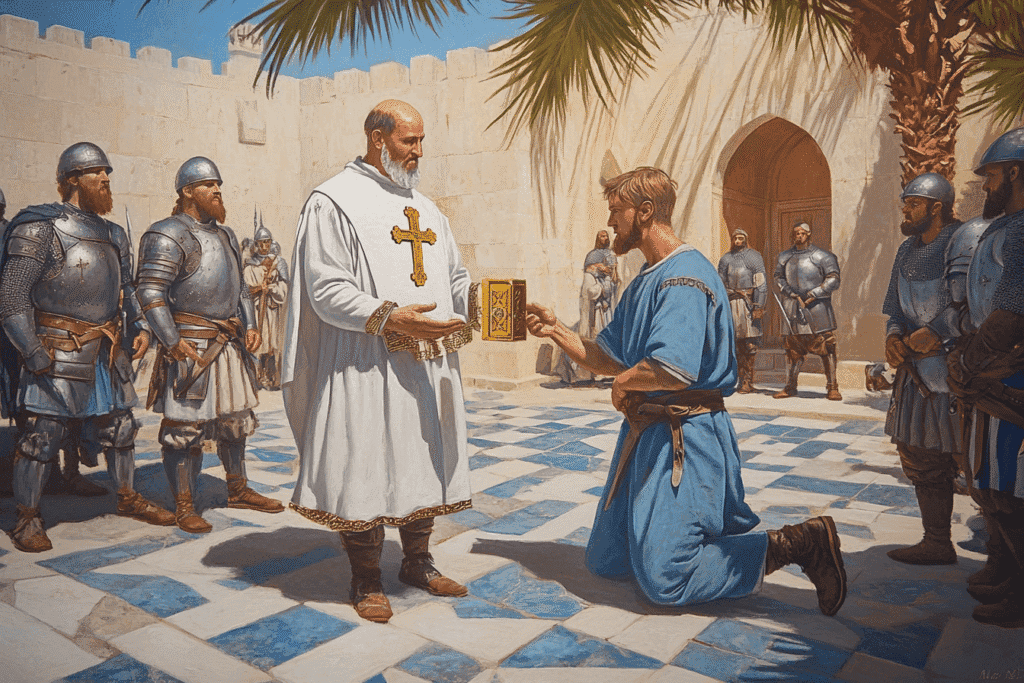

Sigurd’s arrival in Jerusalem marked a historic moment—the first time a European monarch personally led troops to the Holy Land. He was warmly welcomed by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem and quickly integrated into ongoing military efforts. Baldwin enlisted Sigurd’s assistance in capturing Sidon, a coastal city fortified by Fatimid forces since 1098.

The Siege of Sidon

The siege culminated on December 5, 1110, with a decisive victory for the crusaders. The city’s capture bolstered Christian control over key trade routes along the Levantine coast. As a token of gratitude for his contributions, Baldwin presented Sigurd with a fragment of the True Cross—a relic revered across Christendom. This gift symbolized both Baldwin’s respect for Sigurd and Norway’s newfound prominence among European powers.

Return Journey: Constantinople and Beyond

After leaving Jerusalem, Sigurd sailed north to Cyprus before arriving in Constantinople (Miklagard). There, he was received with great honor by Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. The emperor gifted him horses in exchange for Sigurd’s entire fleet and some men—an act that underscored mutual respect between two powerful leaders.

Sigurd chose an overland route back to Norway that took him through Bulgaria, Hungary, Swabia, Bavaria, and Denmark. Along the way, he met rulers such as Emperor Lothar II of the Holy Roman Empire and King Niels of Denmark. These encounters further solidified Norway’s diplomatic ties across Europe.

Impact on Norway

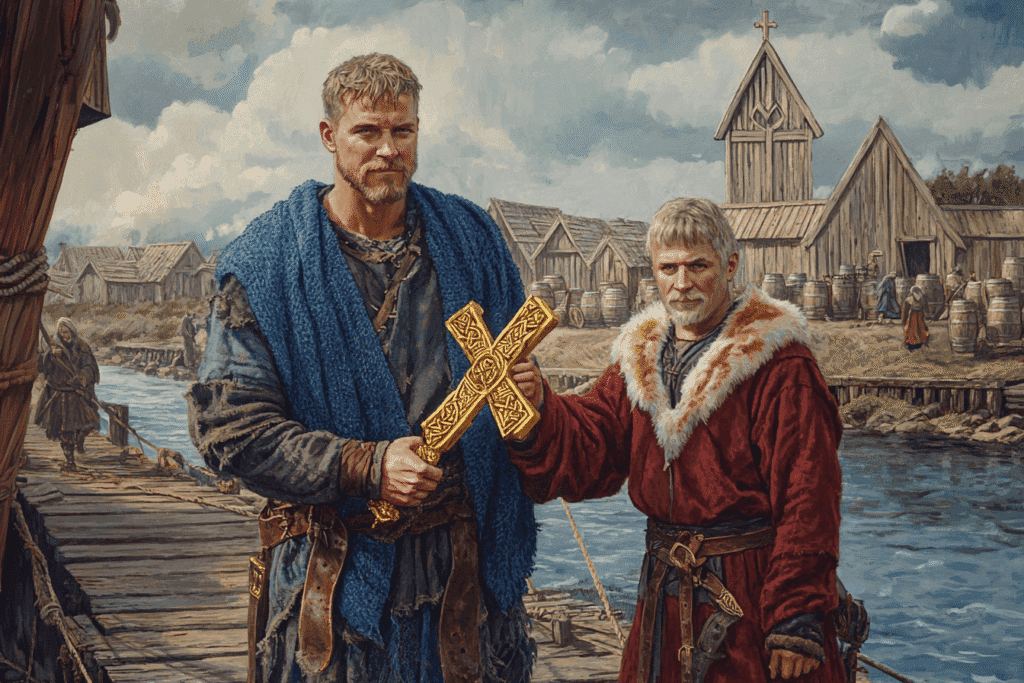

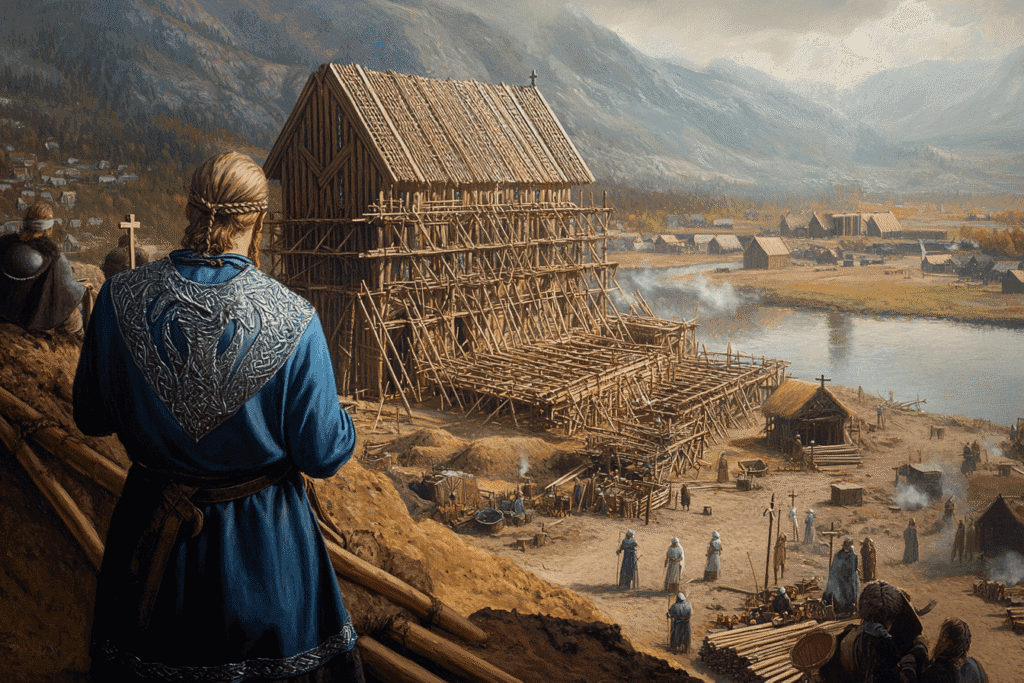

Sigurd returned home in 1111 to find Norway thriving under Øystein’s stewardship. The kingdom had grown more prosperous during his absence due to Øystein’s reforms and investments in infrastructure. Sigurd joined his brother in ruling again and contributed significantly to Norway’s cultural and religious development by strengthening Christianity.

While his unbroken record of victories during the crusade elevated Norway’s status among European powers. Sigurd continued his martial exploits later in life. In 1123, he led another crusade—this time against pagan worshippers in Småland (modern-day Sweden). While less celebrated than his journey to Jerusalem, this campaign reinforced his image as a defender of Christianity.

The Divorce Controversy

Sigurd’s desire for divorce became a defining episode later in his reign. He sought to dissolve his marriage to the daughter of Grand Prince Mstislav I of Kiev, in favor of Cecilia, the daughter of a prominent Norwegian nobleman. This decision sparked significant controversy within the church and among his subjects. Divorce was not easily granted in medieval Christendom, as marriage was considered a sacred bond under ecclesiastical law.

When Sigurd approached Bishop Magne in Bergen to request a divorce, he faced staunch opposition. The bishop refused to grant the divorce on religious grounds, which frustrated Sigurd. In response, Sigurd took matters into his own hands by installing another bishop further south in Stavanger—a move that demonstrated both his political acumen and disregard for ecclesiastical authority in certain matters.

Sigurd’s establishment of Stavanger as a diocese was not solely motivated by personal reasons; it also reflected his broader efforts to strengthen the Norwegian church. By introducing tithes (a 10% tax for church support) and founding cathedrals and monasteries, Sigurd ensured that the clergy gained wealth and influence during his reign. These actions helped consolidate his power while simultaneously legitimizing his controversial decisions.

Legacy

Sigurd I Magnusson remains one of Norway’s most iconic kings—not only for his role as a crusader but also for embodying the adventurous spirit of Viking culture while embracing medieval Christendom. Through diplomacy, military success, and religious devotion, Sigurd earned his epithet Jórsalafari (“Jerusalem-farer”). His epic life from Viking to crusader mirroring the Norse transition from Dark Age to Medieval.