Harold Godwinson, also known as Harold II, was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, reigning for a mere nine months in 1066 before his untimely death at the Battle of Hastings. His short reign marked the end of Anglo-Saxon rule in England and ushered in the Norman era, forever changing the course of English history. Despite his brief time on the throne, Harold’s life and reign were filled with drama, intrigue, and military prowess that continue to captivate historians and history enthusiasts alike.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Harold Godwinson’s meteoric rise through the ranks of Anglo-Saxon nobility began in his youth, propelled by his family’s powerful connections and his own political acumen. Born around 1022, Harold was the son of Godwin, Earl of Wessex, one of the most influential figures in Anglo-Saxon England and Gytha, a Danish noblewoman

Harold’s ascent to power coincided with a pivotal moment in English royal history. In 1045, his sister Edith married King Edward the Confessor, solidifying the Godwin family’s ties to the throne. Around this time, Harold was appointed Earl of East Anglia, a significant position that marked his entry into the highest echelons of Anglo-Saxon aristocracy.

As Earl of East Anglia, Harold quickly proved his worth. In 1045, he led the English fleet in successful maneuvers against Magnus of Norway, demonstrating both his military prowess and his value to the crown. This action, along with his family’s growing influence, cemented the Godwins’ position as the most powerful noble family in England.

However, the relationship between the Godwins and King Edward was not without its tensions. In 1051, a bitter rivalry erupted between the family and the king. Edward, seeking to reduce the Godwins’ influence and surround himself with Norman advisors, took action against the family. This conflict reached a climax when Edward exiled the Godwins, forcing Harold to seek temporary refuge in Ireland.

The exile was short-lived, however. In 1052, the Godwins returned to England with a formidable force, compelling Edward to reinstate them to their former positions. This event not only showcased the family’s resilience but also highlighted Harold’s growing importance within the Anglo-Saxon power structure, setting the stage for his eventual rise to the throne in 1066.

A year after their return from exile, Harold’s father died and Harold inherited the powerful earldom of Wessex, making him one of the most influential figures in the kingdom. Wessex was an enormous territory that covered about a third of England, giving Harold control over a vast swath of the country.

The Welsh Campaign

Harold’s reputation as a skilled military commander grew throughout his career. One of his most notable achievements was the successful campaign against Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, King of Wales, in 1063-64.

In the waning months of 1062, the death of his staunch Mercian ally, Ælfgar, left the Welsh king exposed. Harold Godwinson seized upon this vulnerability with characteristic ruthlessness.

With the blessing of King Edward, Harold launched a strike against Gruffydd’s stronghold at Rhuddlan. The attack came without warning, a testament to the element of surprise that would later serve Harold well on other battlefields. Gruffydd, caught off-guard but not unprepared, narrowly evaded capture. As Harold’s men poured into the royal compound, the Welsh king slipped away to the safety of his ships, though not before witnessing the destruction of much of his fleet.

The following spring saw a coordinated assault on Welsh territory. Harold’s brother, Tostig, led a formidable force into the heartland of North Wales, while Harold himself commanded a naval expedition that probed the southern coastline before swinging north to rendezvous with Tostig’s army. This pincer movement, executed with military precision, forced Gruffydd to retreat into the forbidding peaks of Snowdonia.

It was here, amidst the mist-shrouded valleys and craggy slopes, that Gruffydd ap Llywelyn met his end. The circumstances of his death remain shrouded in mystery and conflicting accounts. What is certain is the grisly aftermath. Gruffydd’s severed head, along with the ornate figurehead of his personal ship, were delivered to Harold Godwinson as trophies of victory. These gruesome relics were then forwarded to King Edward, a stark message that the threat from Wales had been neutralized.

The Succession Crisis and Coronation

Due to a doubling of taxation in 1065 by Tostig in his capacity as Earl of Northumbria, threatening to plunge England into civil war, Harold supported Northumbrian rebels against his brother, and replaced him with Morcar. This led to Harold’s marriage alliance with the northern earls but fatally split his own family, driving Tostig into alliance with King Harald Hardrada of Norway.

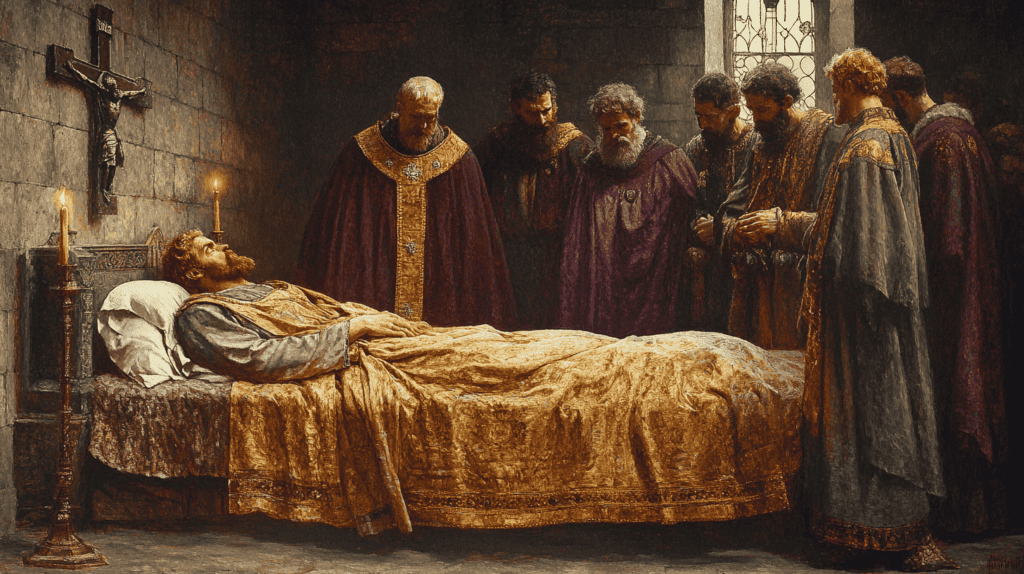

When Edward the Confessor died childless on January 5, 1066, the succession to the English throne was far from clear. Harold, as the most powerful nobleman in the land and brother-in-law to the late king, had a strong claim. However, he faced challenges from two formidable opponents: Harald Hardrada of Norway and William, Duke of Normandy.

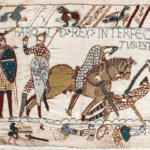

According to Norman sources, including the famous Bayeux Tapestry, Harold had sworn an oath to William in 1064 to support his claim to the English throne. This alleged oath would later be used by the Normans to justify their invasion. However, the circumstances surrounding this oath are disputed, and it’s possible that Harold made the pledge under duress while shipwrecked in Normandy.

Despite the competing claims, the Witenagemot, the council of Anglo-Saxon nobles, chose Harold as the new king. He was crowned on January 6, 1066, just one day after Edward’s death, in Westminster Abbey. This swift coronation was likely an attempt to solidify Harold’s position and prevent any immediate challenges to his rule.

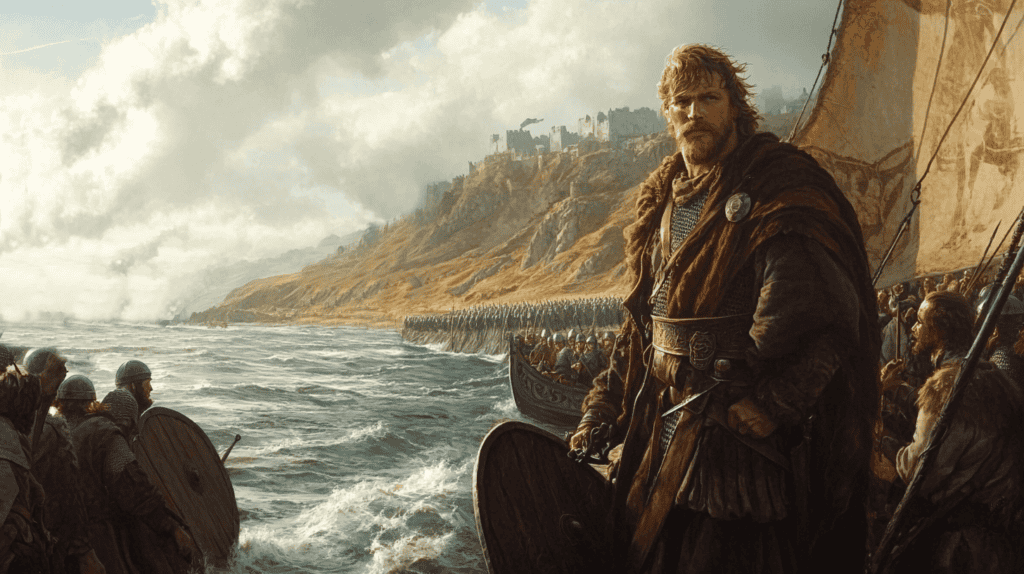

The Norwegian Invasion and the Battle of Stamford Bridge

In September 1066, Harald Hardrada, the King of Norway, invaded England with the support of Harold’s estranged brother, Tostig. Despite the formidable threat posed by the Norwegian forces, Harold moved swiftly and decisively. He marched his army north and engaged the invaders at the Battle of Stamford Bridge on September 25, 1066. As in his campaign against Gruffydd ap Llywelyn two years previously, Harold made a surprise attack, catching the Norwegians unprepared and with their armor still in their longships.

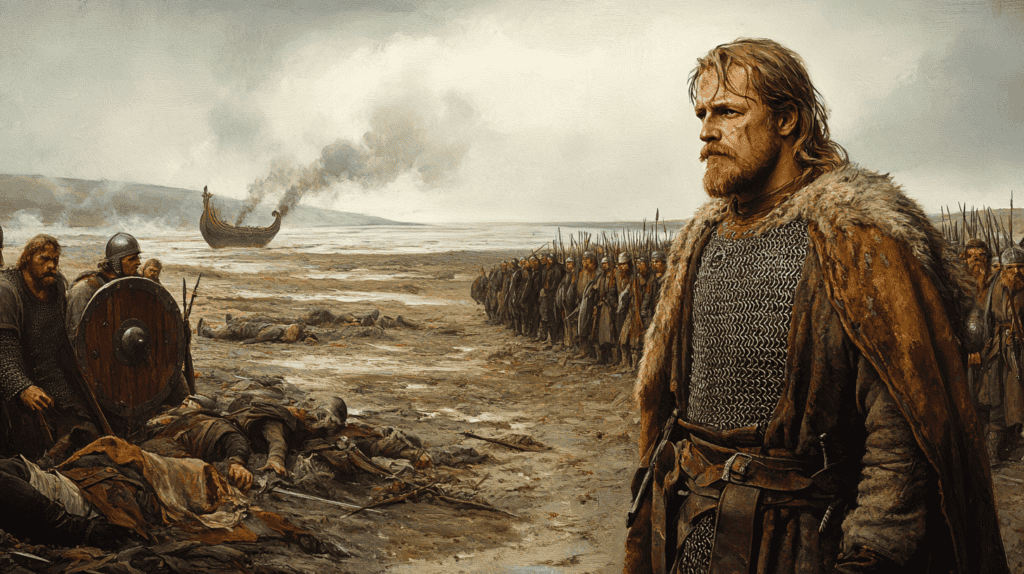

The battle was a resounding victory for Harold. Both Harald Hardrada and Tostig were killed, and the Norwegian army was so thoroughly defeated that only 25 ships were needed to transport the survivors back to Norway, compared to the over 300 ships they had arrived in. This victory showcased Harold’s exceptional military leadership and tactical skills, but an even greater adversary was just landing in southern England.

The Norman Invasion and the Battle of Hastings

While he had successfully repelled the Norwegian invasion in the north, a greater threat loomed from across the English Channel. William of Normandy, claiming that Edward had promised him the throne and that Harold had sworn to support his claim, prepared to invade England.

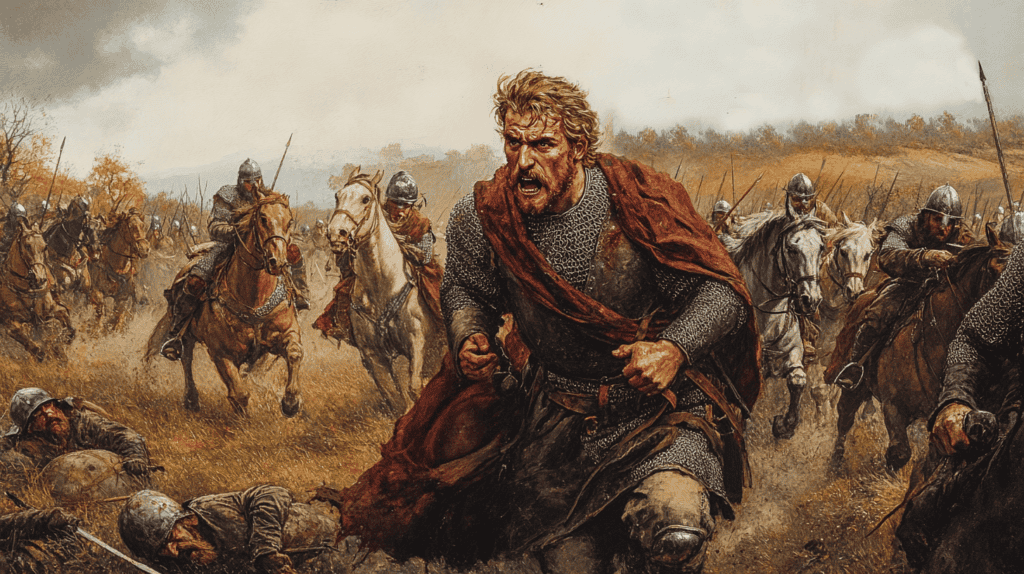

After his victory at Stamford Bridge, Harold was forced to march his army south to meet the Norman threat. It was a remarkable feat of logistics and endurance, covering approximately 250 miles in just a few days. On October 14, 1066, Harold’s forces met William’s army near the town of Hastings in southern England.

The Battle of Hastings remains the most pivotal moment in English history. Harold’s army, primarily composed of infantry, faced William’s forces, which included cavalry and archers. The battle lasted all day, with the outcome hanging in the balance for hours. According to legend, and as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, Harold was killed by an arrow to the eye. However, some accounts suggest he was cut down by Norman knights in the final stages of the battle.

Regardless of the exact manner of his death, Harold’s fall marked the end of both the battle and the Anglo-Saxon era in England. With Harold’s demise, effective resistance to the Norman invasion crumbled, and William of Normandy would soon be crowned as the new King of England, ushering in a new chapter in the country’s history.

Harold II’s reign, though lasting less than a year, represents a crucial turning point in English history. His victory at Stamford Bridge and subsequent defeat at Hastings encapsulate the dramatic events of 1066, a year that would change the course of English history forever. As the last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold stands as a symbol of the end of one era and the beginning of another.

I enjoyed this thoroughly thank you. Looking forward to more.

Thanks for your feedback. It was a pleasure writing it!