The House of Wisdom in Baghdad, or Bayt al-Hikmah, was a legendary center for scholarship and intellectual exchange during the Islamic Golden Age, renowned for facilitating the translation and expansion of ancient knowledge and catalyzing great scientific advancements. Unfortunately, the Mongols who placed little value on scientific knowledge captured Baghdad after a seige.

Origins and Establishment

The House of Wisdom was founded during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in the late 8th century. Originally conceived as a library to store rare books and manuscripts, it was rapidly expanded by his son, al-Ma’mun, in the early 9th century into an elaborate academy, research center, and intellectual powerhouse. Housing scholars from across the world – representing a myriad of cultures and religions – it quickly became the focal point for the accumulation, translation, and dissemination of knowledge.

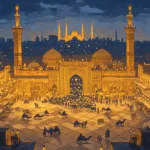

Architecture and Growth

The House of Wisdom was rumored to be a sprawling complex with multiple halls and rooms dedicated to various purposes: translation, research, reading, copying, and even astronomical observation. Housed in eastern Baghdad’s Al Rusafa district, it featured an internal courtyard surrounded by two-story halls, topped by domed chambers, and included spaces for residential scholars. Its architectural grandeur reflected the Abbasid commitment to scholarly pursuits and cultural prestige.

The Translation Movement

What set the House of Wisdom apart was its role at the heart of the Translation Movement. Scholars there translated works from Greek, Persian, Syriac, Sanskrit, and other languages into Arabic, making the center instrumental in salvaging and disseminating ancient knowledge from across the world. This included foundational texts in mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, medicine, and engineering.

The center’s translators and scientists included figures from a variety of backgrounds. Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Hindu, and Muslim scholars worked side by side, translating pivotal works such as those of Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy, Galen, and many Persian and Indian mathematicians. Their collective efforts ensured that vital ancient knowledge was neither lost to time nor to the disruptions that had rocked Europe and the Mediterranean after the fall of Rome.

Scientific Innovation and “Big Science”

Encouraged by caliphs who valued knowledge, such as al-Ma’mun, the House of Wisdom did not merely transmit old ideas, it also fostered innovation and synthesis. Al-Ma’mun, inspired by his dream debates with Aristotle, sponsored multi-disciplinary teams to tackle grand challenges: measuring the exact circumference of the Earth, mapping the world, refining astronomical tables, and constructing observatories. These initiatives were arguably some of the earliest state-funded “big science” projects in history.

Some of the most important scientific minds of the era found their home at the House of Wisdom:

- Al-Khwarizmi, often called the “father of algebra,” whose influential works in mathematics formed the basis of modern algebra and algorithms.

- The Banu Musa brothers, pioneers in mechanical engineering and automation.

- Al-Razi (Rhazes), one of the greatest physicians of the Islamic world.

- Hunayn ibn Ishaq, master translator, and medical scholar.

Their collective work advanced fields such as algebra, trigonometry, chemistry, and engineering, setting the foundation for much of today’s science and technology.

Cultural Exchange and Tolerance

The House of Wisdom’s unique milieu fostered an atmosphere of tolerance and dynamic cross-cultural exchange. Baghdad, capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, was a melting pot: Persian, Arab, Greek, Indian, and Jewish traditions all found space in its intellectual heart. The library welcomed scholars from throughout the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and beyond, including those persecuted or excluded from other lands.

The language of exchange at the House of Wisdom was often Arabic, but the center also embraced work in Greek, Persian, Syriac, Hebrew, Sanskrit, and occasionally Latin. This cosmopolitan approach ensured not only the preservation of vast corpora but also the development of new vocabularies and concepts to advance scientific and philosophical discourse.

Decline and Catastrophe

The turning point for the House of Wisdom came with changing political winds. Whereas caliphs like Harun al-Rashid and al-Ma’mun promoted rationalism and learning, later rulers such as al-Mutawakkil prioritized more conservative religious interpretations and curtailed public support for unfettered scientific inquiry. Gradually, the once-vibrant institution declined.

The fatal blow came in 1258, when the Mongols under Hulagu Khan besieged Baghdad. The House of Wisdom was destroyed along with the city’s other libraries – the loss of its manuscripts and scientific treasures was so immense that, legend says, the Tigris River ran black with ink from the ruined books. Although some sources claim hundreds of thousands of manuscripts were rescued, the destruction marked an end to the institution’s golden legacy.

Legacy and Historiographical Debate

For centuries, the House of Wisdom stood as a symbol of the heights of civilization: a beacon of learning where knowledge from Greece, Persia, India, and beyond was preserved, interpreted, and advanced. Its impacts were profound, helping to trigger the European Renaissance and inform scientific endeavors worldwide.

The cumulative evidence from manuscripts, historical records, and the scientific revolution it helped ignite ensures its place in the history of human knowledge.