Alan I, known as “the Great,” was a remarkable figure in Breton history who ruled as Count of Vannes and Duke of Brittany from 876 until his death in 907. His reign marked a significant period in Brittany’s history, as he was the only ruler to hold the title of King of Brittany through a grant from the Holy Roman Emperor.

Rise to Power

Alan’s journey to power began in 876 when he succeeded his brother Pascweten as Count of Vannes. This succession thrust him into a power struggle with Judicael of Poher for leadership of Brittany. Alan represented the interests of southeastern Brittany, while Judicael championed the western Breton cause. Despite their initial rivalry, the two leaders eventually found common ground in the face of a greater threat: the Vikings.

The Viking Menace

The late 9th century was a tumultuous time for Brittany, as it faced frequent Viking incursions. These Norse raiders posed a significant threat to the stability and prosperity of the region. Recognizing the gravity of the situation, Alan and Judicael set aside their differences to present a united front against the invaders.

Their alliance proved crucial in 888 when the Battle of Questembert took place. This conflict, despite victory over the Vikings, resulted in the death of Judicael, leaving Alan as the sole leader of Brittany. With this newfound authority, Alan wasted no time in confronting the Viking threat head-on.

In 890, Alan achieved a decisive victory against the Vikings at Saint-Lô. He decisively defeated the Norse forces, and once their enemy was routed the Bretons chased them into a river, where many of them drowned. This victory was a turning point in Brittany’s struggle against the Vikings and cemented Alan’s reputation as a formidable leader.

Expansion of Breton Territory

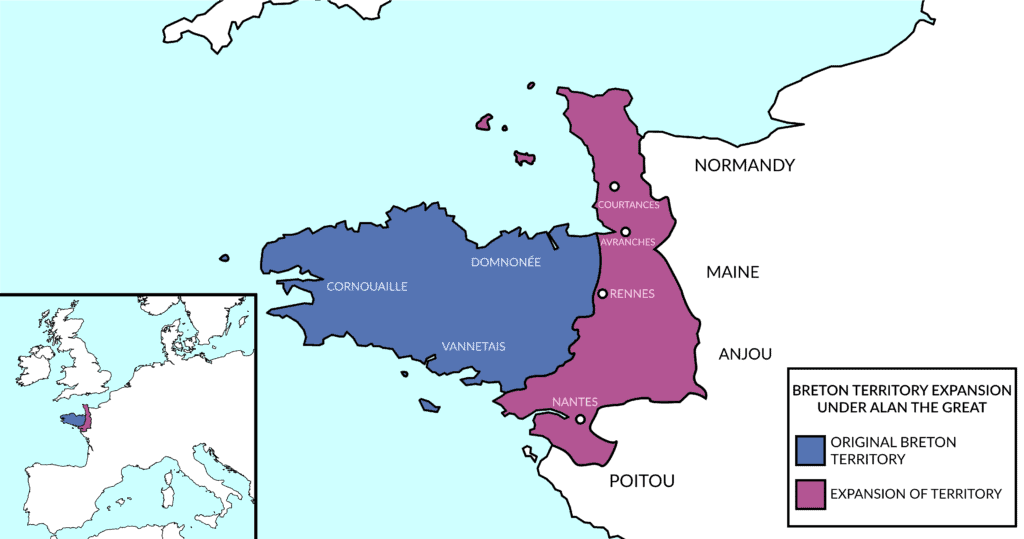

Following Judicael’s death, Alan’s rule expanded significantly, encompassing a territory that rivaled that of his predecessor, Salomon. His domain included not only the traditional Breton territories of Domnonée, Cornouaille, and Vannetais but also extended to include the Frankish counties of Rennes, Nantes, Coutances, and Avranches.

Alan’s influence stretched even further, incorporating western parts of Poitou (known as the pays de Retz) and Anjou. To the east, his rule reached as far as the river Vire. This extensive territory made Alan the first Breton ruler to govern such a vast area with minimal internal opposition, and he would be the last to rule over this entire Franco-Celtic bloc.

Diplomatic Challenges

Despite his military successes and territorial expansion, Alan faced diplomatic challenges during his reign. His most formidable opponent was Fulk I of Anjou, who contested control over the Nantais region. However, historical evidence suggests that Alan maintained the upper hand in this dispute throughout his lifetime.

The Title of King

One of the most intriguing aspects of Alan’s reign was his acquisition of the title “King of Brittany” (rex Brittaniæ). This title was likely granted by Charles the Fat, who ruled as Holy Roman Emperor from 881 to 887. The circumstances surrounding this grant of royal title are not entirely clear, but several factors point to its likelihood.

A charter dated between 897 and 900 mentions prayers being said for the soul of “Karolus” on Alan’s behalf at the monastery of Redon. This Karolus is believed to be Charles the Fat, suggesting a connection between the emperor and the Breton ruler. Furthermore, Charles the Fat is known to have had contacts with Nantes in 886, making it plausible that he communicated with Alan during this time.

The granting of the royal title to Alan aligns with Charles the Fat’s broader strategy of effective rule across his empire. The emperor was known to elevate former enemies or those with tenuous ties to the empire to positions of standing in exchange for their loyalty. This approach is exemplified by his treatment of the Viking leader Godfrid.

Godfrid, a Danish Viking leader of the late 9th century, had a complex relationship with Emperor Charles the Fat. Initially, Godfrid posed a significant threat to Charles’s empire, ravaging Flanders in 880 and devastating cities in Lotharingia in 882. Unable to defeat Godfrid militarily, Charles the Fat was forced to negotiate with the Viking leader.

In 882, Charles reached an agreement with Godfrid at Asselt. As part of this pact, Charles appointed Godfrid as Duke of Frisia and made him his vassal. To solidify this alliance, Charles gave Godfrid Gisela, daughter of Lothair II, as his wife. Additionally, Godfrid accepted Christianity and was baptized, with Charles standing as his godfather

Carolingian Influence

Throughout his reign, Alan demonstrated a clear affinity for Carolingian symbols and practices. He utilized Carolingian regalia and employed Carolingian forms in his charters. This adoption of Frankish royal customs likely served to legitimize his rule both within Brittany and in the eyes of his powerful neighbors.

Alan’s power continued to grow during the relatively weak reigns of Odo and Charles III of France. This period of Frankish instability allowed Alan to consolidate his authority and expand his influence further.

Legacy and Aftermath

Alan I’s reign marked the apex of Breton power and independence in the early medieval period. His ability to unite Brittany, repel Viking invaders, and expand Breton territory earned him the epithet “the Great”. However, the golden age of Breton independence would not outlast him for long.

Upon Alan’s death in 907, Brittany faced a power vacuum that the Vikings were quick to exploit. The region fell under Norse control for nearly three decades, until Alan’s grandson, Alan II, managed to re-establish Christian rule in 936.

Alan II’s return to Brittany is a tale worthy of legend. Raised in the court of King Æthelstan of England, the young Alan was described as strong in body and very courageous. His physical prowess was such that he reportedly preferred to hunt wild boars and bears with wooden staffs rather than iron weapons.

In 936, at the invitation of a monk named Jean de Landévennec and with the support of King Æthelstan, Alan II landed at Dol to reclaim his grandfather’s legacy. By 937, he had managed to push the Norsemen back to the Loire, effectively becoming master of most of Brittany.

The Chronicle of Nantes provides a vivid account of Alan II’s return:

“The city of Nantes remained for many years deserted, devastated and overgrown with briars and thorns, until Alan Crooked Beard, grandson of Alan the Great, arose and cast out those Norsemen from the whole region of Brittany and from the river Loire, which was a great support for them.”

Alan II’s victory was made complete in August, 939, when, with the aid of Judicael (Berengar), Count of Rennes, and Hugh I, Count of Maine, he fought the Norse at the Battle of Trans-la-Forêt. The coalition had been campaigning against the Northmen for three long and hard-fought years, with the battle at Trans-la-Forêt serving as the culmination of their efforts.

The battle was intense and hard-fought, but as the conflict progressed, the Viking left flank eventually collapsed, which proved to be a turning point in the engagement. This collapse freed up many Breton cavalry and light horse units, allowing them to seek new targets and press their advantage. As the tide of battle turned against them, the surviving Vikings were forced to retreat and form a new defensive line. However, the Breton forces, buoyed by their success and the momentum of their attack, ultimately prevailed. The 1st August was subsequently declared a national holiday, marking the liberation of Brittany from Viking control.

The End of an Era

While Alan II’s reconquest of Brittany was undoubtedly a significant achievement, it’s important to note that the Brittany he ruled was never as extensive as it had been under his grandfather, Alan I. The title of “King of Brittany” was not used by subsequent Breton rulers, marking the end of an era in Breton history.

Conclusion

Alan I “the Great” of Brittany stands as a pivotal figure in the history of medieval Brittany and France. His reign represented a high point of Breton power and independence, characterized by military success against the Vikings, territorial expansion, and diplomatic maneuvering within the complex political landscape of 9th-century Francia.

Alan’s acquisition of the royal title, likely granted by Charles the Fat, underscores the complex relationships between Brittany and the Frankish kingdoms during this period. His adoption of Carolingian symbols and practices demonstrates a sophisticated approach to statecraft, balancing local Breton traditions with the political realities of the wider Frankish world.

The legacy of Alan I extended beyond his lifetime, inspiring future generations of Breton leaders, most notably his grandson Alan II. While the independent Kingdom of Brittany did not survive long after Alan I’s death, the memory of his achievements continued to shape Breton identity and aspirations for centuries to come.