In the early 12th century, the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem faced significant challenges in the Holy Land. Following the disastrous defeat of the Crusaders at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis in 1119, King Baldwin II of Jerusalem sent an urgent appeal for assistance to Pope Calixtus II and Doge Domenico Michiel of Venice. This call for help would lead to one of the most significant naval expeditions of the Crusader era: the Venetian Crusade of 1122-1124.

The Call to Arms

The Pope’s emissaries delivered a letter to the Venetians, imploring them to have mercy on the Christians of the East by coming swiftly to their aid. Doge Michiel, recognizing both the religious significance and potential commercial benefits of such an expedition, convened an assembly of all citizens at San Marco. In a stirring speech, he rallied support for the crusade.

The response from the Venetian people was overwhelming. With shouts of assent, the doge himself took the cross, followed by countless citizens. The city mobilized for war, ordering all Venetians engaged in overseas commerce to return home in preparation for the crusade.

The Venetian Fleet Sets Sail

In August 1122, a formidable Venetian fleet of approximately 120 major vessels departed from the Venetian lagoon. This impressive armada carried some 15,000 crusaders, a force that would prove crucial in the coming campaign. The fleet’s first stop was Corfu, where they wintered and besieged the Byzantine stronghold in retaliation for Emperor John II Komnenos’s refusal to honor Venetian commercial privileges. It was quite typical of the Venetians to put their commercial interests above the desperate needs of the Christian forces in the Holy Lands.

A Change of Plans

The Venetians’ plans took an unexpected turn in early spring 1123 when they learned of King Baldwin II’s capture by the Turks. Abandoning the siege of Corfu, they immediately set sail for the Holy Lands.

Naval Victory off Ascalon

As the Venetian fleet approached Cyprus, they received intelligence that a powerful Egyptian fleet was threatening Jaffa. Doge Michiel, recognizing the opportunity to strike a decisive blow against the Fatimids, ordered his ships to intercept the enemy fleet.

The ensuing naval battle off the coast of Ascalon would prove to be a masterclass in medieval naval warfare. Michiel employed a clever stratagem, hiding his war galleys behind large transport vessels. This deception led the Fatimids to believe they were encountering an unarmed pilgrimage convoy.

As the Egyptian vessels approached, they found themselves suddenly surrounded by the Venetian war galleys. The battle that followed was decisive, with the Fatimid fleet either captured or destroyed. This tremendous victory effectively handed control of the sea to the Christians, dramatically altering the balance of power in the region.

The Pactum Warmundi

Following their naval triumph, the Venetians proceeded to Acre, where they entered into negotiations with the Franks. The result was the Pactum Warmundi, an agreement that promised the Venetians one-third of Tyre, a quarter in every city in the kingdom, and various privileges in return for their assistance in capturing the important coastal city.

This agreement was a testament to the Venetians’ growing power and influence in the Levant. It also highlighted the desperate situation of the Crusader states, willing to offer such generous terms in exchange for Venetian support.

The Siege of Tyre Begins

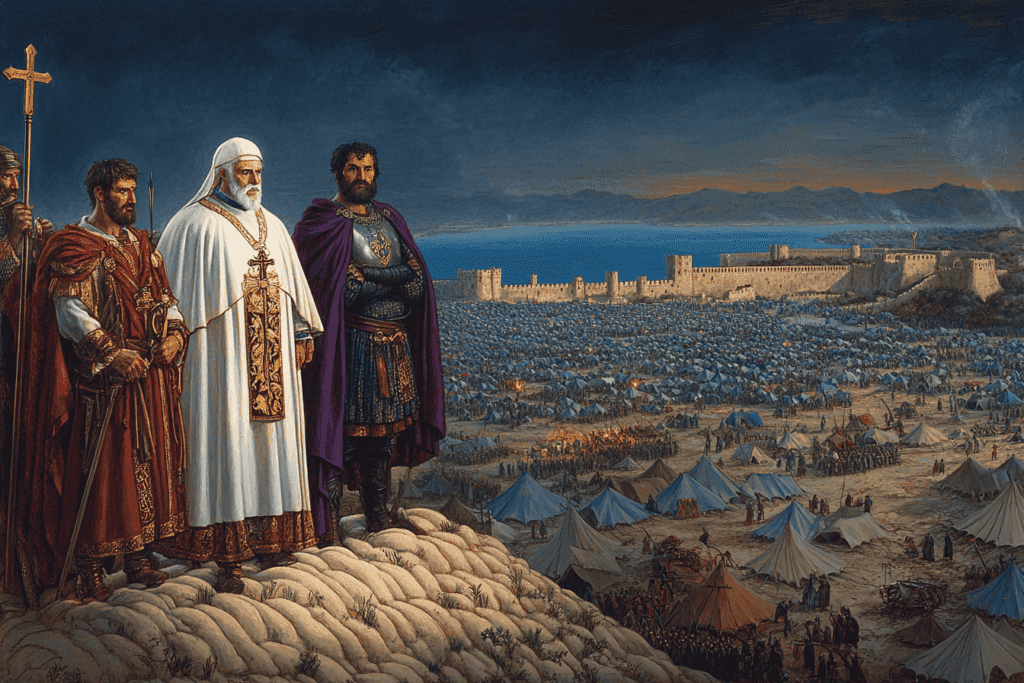

On February 15, 1124, the combined forces of the Venetians and the Franks began the siege of Tyre. The city, now part of modern-day Lebanon, was a formidable target. It was defended by both Saracen and Egyptian forces and protected by a circuit of fortified walls with numerous strong ramparts.

The siege of Tyre was a massive undertaking, involving forces from various Crusader states. The Latin army was led by an impressive coalition, including the Patriarch of Antioch, Doge Michiel of Venice, Pons, Count of Tripoli, and William de Bury, the king’s constable.

Siege Tactics and Technology

The Venetians and Franks employed the full range of medieval siege technology in their assault on Tyre. They constructed siege towers and machines capable of hurling massive boulders to shatter the city’s walls. These siege engines represented the pinnacle of military engineering at the time and were crucial in wearing down the city’s defenses.

However, the defenders of Tyre were not passive in the face of this onslaught. They too built engines, hurling rocks at the besiegers’ siege towers in a deadly game of medieval artillery duels. The back-and-forth nature of this siege warfare highlighted the technological parity between the attackers and defenders, making for a prolonged and grueling engagement.

The Naval Blockade

While the land assault battered Tyre’s walls, Doge Michiel implemented a crucial naval strategy. He positioned his fleet to occupy a narrow space blocking the harbor, effectively cutting off the besieged city from any external communication or assistance. This naval blockade would prove to be a decisive factor in the siege, slowly strangling the city’s resources and morale.

The Siege Drags On

As the siege stretched into months, both sides faced increasing hardships. The citizens of Tyre began to run short of food, sending urgent calls for help to their allies. Meanwhile, the Crusader forces faced their own challenges, including the need to maintain supply lines and keep their large army fed and equipped for an extended campaign.

A Turning Point

The tide began to turn against Tyre when Balak, a powerful Muslim leader, died while besieging the city of Manbij. This event weakened the potential for outside relief of the besieged city. Toghtekin, the atabeg of Damascus, advanced towards Tyre but withdrew without fighting when confronted by the forces of Count Pons of Tripoli and Constable William.

The Pigeon Stratagem

As the siege entered its final stages, a stroke of luck favored the Crusaders. They managed to capture a carrier pigeon flying into Tyre, bearing a message of promised help and deliverance from the Sultan of Damascus. In a clever ploy, the Crusaders replaced this message with a forged one, stating that succor was impossible and advising the besieged to surrender.

This psychological warfare tactic proved highly effective. The altered message, delivered by the unsuspecting pigeon, significantly demoralized the defenders and contributed to their decision to negotiate surrender terms.

Negotiations and Surrender

In June 1124, after months of grueling siege warfare, Toghtekin sent envoys to negotiate peace. The discussions were lengthy and difficult, reflecting the high stakes for both sides. Eventually, terms were agreed upon that allowed those who wished to leave the city to depart with their families and property, while those who chose to stay could keep their houses and possessions.

These relatively generous terms were not universally popular among the Crusaders, some of whom had hoped to loot the wealthy city. However, the agreement likely hastened Tyre’s surrender and prevented further bloodshed.

The Fall of Tyre

On July 7, 1124, after nearly five months of siege, Tyre finally surrendered to the Crusader forces. The fall of this strategically crucial city marked a significant victory for the Kingdom of Jerusalem and its Venetian allies.

As the Crusader forces entered Tyre, they were struck by the city’s impressive defenses and architecture. William of Tyre, a chronicler of the Crusades, wrote: “They admired the fortifications of the city, the strength of the buildings, the massive walls and lofty towers, the harbour so difficult to access. They had only praise for the resolute perseverance of the citizens who, despite the pressure of terrible hunger and the scarcity of supplies, had been able to ward off surrender for so long.”

The siege had indeed taken a severe toll on Tyre’s resources. When the Crusaders took possession of the city, they found only five measures of wheat remaining, a testament to the effectiveness of their blockade and the defenders’ tenacity.

Venetian Rewards

As per the Pactum Warmundi, the Venetians were granted one-third of Tyre and its surrounding territory, along with significant commercial privileges. This reward reflected the crucial role played by the Venetian fleet in the siege and marked a significant expansion of Venetian influence in the Levant.

The Venetians wasted no time in establishing their presence in Tyre. They quickly built three churches and set up commercial houses, laying the groundwork for a thriving trade network. This new and brisk trade with Syria would prove to be a significant boon for Venice, though it came at the expense of their Byzantine rivals in Constantinople.

Aftermath and Legacy

The capture of Tyre was a pivotal moment in the history of the Crusader states. It marked the beginning of a period of expansion for the Kingdom of Jerusalem under Baldwin II, with the kingdom reaching its greatest territorial extent in the years following this victory.

For Venice, the crusade of 1122-1124 represented a major triumph of both military prowess and diplomatic maneuvering. Their naval victory off Ascalon and the crucial role they played in the capture of Tyre cemented their status as a major power in the Mediterranean. The commercial privileges they gained in the Levant would prove immensely valuable, fueling Venice’s rise as a maritime trading empire.

The crusade also had significant implications for Venice’s relationship with the Byzantine Empire. On their journey home, the Venetians raided Byzantine territories, using their military might to force Emperor John II Komnenos to confirm and extend their trading privileges with the empire. This aggressive approach to diplomacy would characterize Venice’s dealings with Constantinople for centuries to come. At its most extreme, the Venetians even managed to divert the Fourth Crusade from its original goal of reclaiming Jerusalem to the attack and capture Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, to support Venetian financial interests.