The Ghana Empire, also known as Wagadou, stands as the first major agrarian and trading empire of West Africa, laying the groundwork for centuries of regional prosperity and cultural exchange. Its story is a tapestry woven from legend, innovation, and the relentless pursuit of wealth and power.

Origins: Where Legend Meets History

The precise origins of the Ghana Empire are shrouded in both myth and scholarly debate. Some traditions trace its beginnings as early as 100 CE, with the Soninke people settling in southeastern Mauritania. Other sources point to a foundation in the 4th or even 8th century, but most historians agree that the empire truly began to rise in the 8th or 9th century, with the first written mention of its ruling dynasty appearing around 830 CE. The Soninke, united under legendary early kings known as Dinga Cisse or Kaya-Magha, forged a confederation of tribes into a centralized state, giving rise to a new power in the Sahel.

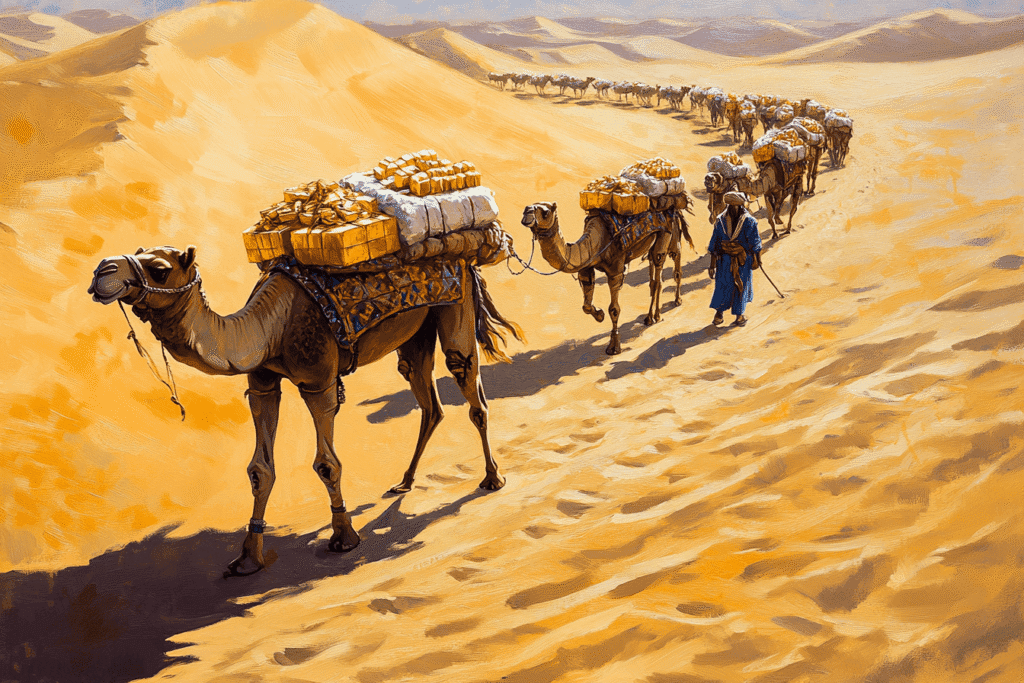

Key Moment: The Camel Revolution and the Rise of Trade

A key moment in the empire’s formation was the introduction of the camel to the western Sahara in the 3rd century. This transformed ancient, sporadic trade routes into a robust trans-Saharan network, linking North Africa to the gold-rich lands south of the desert. Ghana’s strategic location between the Senegal and Niger Rivers allowed it to control and tax this lucrative trade, especially in gold, salt, and ivory. The empire earned its legendary wealth by acting as the gatekeeper between the gold fields of Bambuk and Buré and the markets of the Mediterranean world.

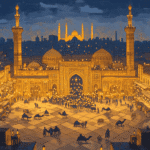

The Capital: Koumbi Saleh, City of Gold

At the heart of the Ghana Empire lay its capital, Koumbi Saleh. Described by the 11th-century geographer Al-Bakri, the city was actually two towns: one inhabited by the king and his court, the other by Muslim merchants and traders. Recent excavations reveal a sprawling urban center with mosques, palaces, and bustling markets – a testament to the empire’s cosmopolitan character and its role as a hub of commerce and culture.

“The king has a palace and a number of domed dwellings all surrounded with an enclosure like a city wall… Around the king’s town are domed buildings and groves and thickets where the sorcerers of these people, men in charge of the religious cult, live. In them are their idols and the tombs of their kings.”

— Al-Bakri, 11th century

The Golden Age and Expansion

The Golden Age of the Ghana Empire, spanning roughly from the 9th to the 11th century, marks one of the most remarkable periods in West African history. This era saw Ghana transform from a modest kingdom into a formidable empire renowned for its immense wealth, sophisticated governance, and far-reaching influence.

Ghana’s rulers used their growing resources to expand their political reach. The empire absorbed lesser states, incorporated gold-producing regions to the south, and extended its influence over key trading cities to the north, such as the once-thriving market town of Audaghost. This expansion was not solely achieved through commerce; Ghana maintained a formidable military, with Arab sources claiming the king could field a massive army, further solidifying the empire’s control over its vassals and trade routes

The Coming of Islam and External Pressures

The Golden Age was also a time of vibrant cultural exchange. The influx of Muslim traders from North Africa introduced new religious and intellectual currents to the empire. While the royal court retained traditional beliefs, a thriving Muslim community developed in the capital, building mosques and schools and fostering a spirit of cosmopolitanism that set Ghana apart from its contemporaries

The arrival of Muslim traders and scholars brought new ideas, technologies, and religious influences. However, Ghana’s prosperity also attracted the envy of rivals, particularly the Berber Almoravids, whose invasions and religious zeal in the late 11th century began to undermine the empire’s stability.

Winds of Change: Causes of Decline

By the 11th century, environmental and political forces began to erode Ghana’s dominance. A prolonged drought reduced the productivity of the land, eroding its capacity for agriculture and livestock. This environmental change magnified social pressures, leading to instability and eventual food shortages.

Compounding these challenges, new gold fields were found outside Ghana’s commercial sphere, particularly in the south at Bure (in modern-day Guinea), diminishing Ghana’s economic leverage as trade routes gradually shifted eastward. Within its borders, rebellious vassal states became difficult to control, leading to internal conflict and weakening the central power.

Externally, the empire came under attack from several quarters. The Almoravids— – a Berber Muslim dynasty from the north – launched invasions in the late 11th century, disrupting Ghana’s authority. While the extent of Almoravid rule is still debated, their incursions clearly destabilized the empire and increased pressure on already strained resources. Subsequent generations of rulers struggled with succession crises and diminishing returns from their once-untouchable trading dynasty.

The Rise of Mali and the Final Blow

As Ghana weakened, a new power was rising – the Mali Empire. The Malinke people under Sundiata Keita united against the Sosso ruler Sumanguru, whose earlier conquest of Ghana in 1203 had only sown further turmoil. In 1235, Sundiata defeated Sumanguru at the legendary Battle of Kirina, effectively ending Ghana’s independence and laying the foundations for the Mali Empire.

Absorption into Mali was not immediate annihilation. For a time, Ghana persisted as a vassal state under Mali’s hegemony, with its king accorded a measure of prestige, though stripped of real power. Over the 13th century, the Malian state absorbed Ghana’s territory and networks, consolidating its supremacy in West Africa. Sundiata’s successors expanded this legacy, building an empire famed for both immense wealth – epitomized later by Mansa Musa – and for promoting Islam, scholarship, and trade throughout the region.

A Lasting Legacy

By around 1240, Ghana’s legacy lived on only as a memory and as a foundation upon which Mali’s glory was built. Mali would rule a vast savannah trade empire, presiding over cities like Djenné and Timbuktu, and linking West Africa to the world. The echo of Ghana’s greatness endured in the sophisticated trade, administration, and culture that Mali inherited, transformed, and spread far and wide.