Queen Bertha of Kent stands as a crucial yet often understated figure in the story of England’s Christianization and Dark Ages history. Her life, rooted in the powerful Merovingian dynasty of Frankish Gaul and transplanted into the heart of Anglo-Saxon Kent, bridges two worlds: the fading echoes of Roman Christianity and the nascent kingdoms of post-Roman Britain.

Frankish Origins and Royal Lineage

Born around 565 in Paris, Bertha – sometimes known as Aldeberge – was the daughter of Charibert I, King of Paris, and Ingoberga. Her lineage was illustrious: her grandfather was Chlothar I, and her great-grandparents were Clovis I and Clotilde, the founders of the Merovingian dynasty and the first Frankish royal couple to embrace Christianity. Raised in a court where Christianity was not only a faith but a foundation of royal authority, Bertha absorbed the traditions, rituals, and expectations of a Christian princess.

Her early years were spent near Tours, a city renowned for its association with Saint Martin, one of the most venerated saints in Western Christendom. This environment, steeped in Christian piety and Merovingian culture, would shape Bertha’s worldview and sense of duty.

A Diplomatic Marriage

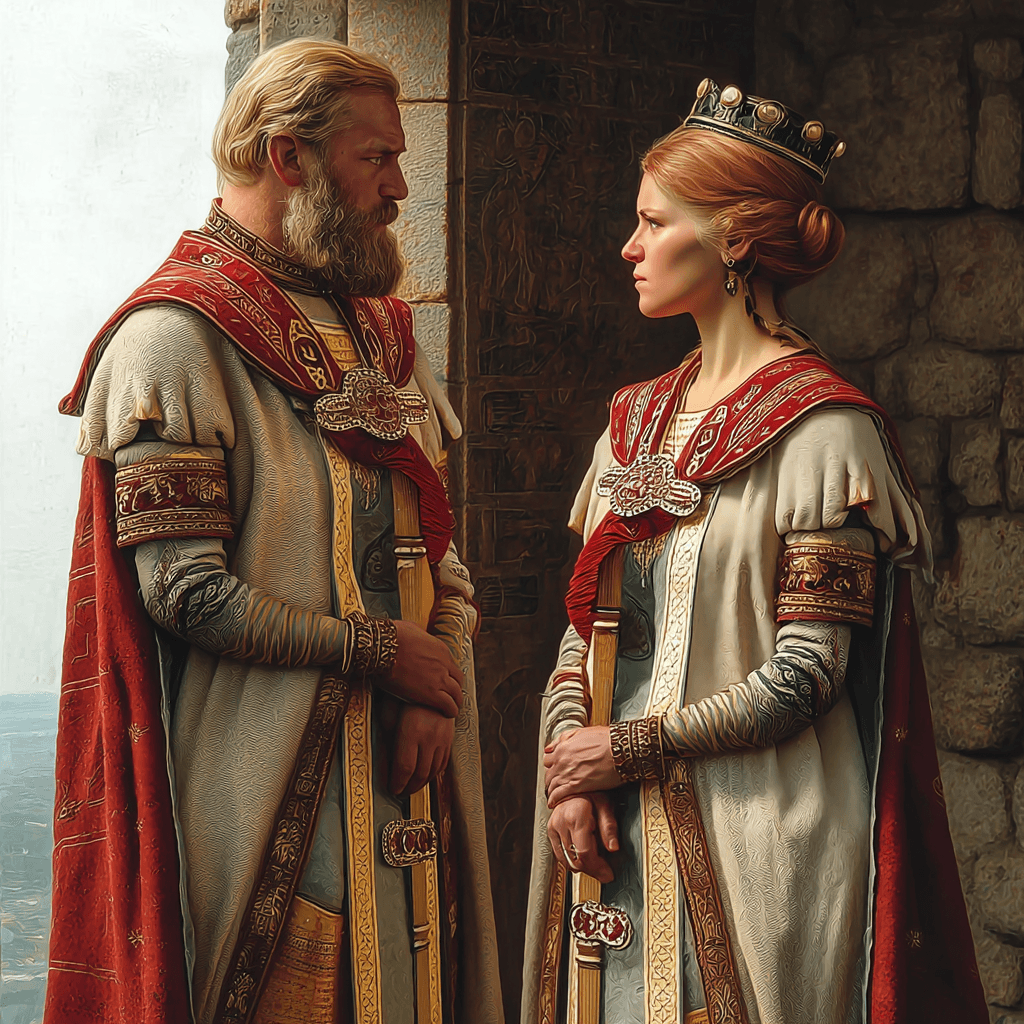

The political landscape of late sixth-century Europe was a tapestry of shifting alliances and rivalries. The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Britain, newly established after the collapse of Roman rule, looked to the continent for connections and legitimacy. Around 580, Bertha married Æthelberht, the pagan King of Kent, a union that was as much a diplomatic alliance as a personal relationship.

The marriage contract contained a crucial stipulation: Bertha was to be allowed to practice her Christian faith freely. She brought with her a Frankish bishop, Liudhard, to serve as her chaplain and spiritual advisor. This condition was not merely a matter of personal devotion; it reflected the growing prestige of Christianity and the Merovingian court’s desire to extend its influence across the Channel.

Upon her arrival in Kent, Bertha found a Roman church outside Canterbury, which she restored and dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. This church, St Martin’s, became her private chapel and the oldest church in the English-speaking world to have maintained continuous Christian worship since 580. The presence of this church, and Bertha’s active use of it, would prove decisive in the religious transformation of Kent.

Life at the Kentish Court

Bertha’s position at the Kentish court was unique. As a foreign princess and a Christian in a pagan land, she navigated a delicate balance between her faith and her role as queen. Her husband, Æthelberht, recognized the political advantages of his marriage but remained initially resistant to conversion. Nevertheless, Bertha’s quiet persistence and the example she set through her devout life laid the groundwork for change.

The court at Canterbury, influenced by Bertha’s Merovingian traditions, became a center of cultural exchange. Bertha introduced elements of Frankish Christian culture, including liturgical practices, art, and perhaps even the Latin language, to southeastern England. Her chapel at St Martin’s served as a beacon for the small but enduring Christian community in Kent, a community that had survived since Roman times but had been largely isolated from the wider Christian world.

The Gregorian Mission

The most significant chapter of Bertha’s life began in 596, when Pope Gregory I, concerned about the spiritual state of the Anglo-Saxons, dispatched a mission led by Augustine, prior of the Roman monastery of St Andrew, to reintroduce Christianity to England. Gregory’s choice of Kent as the mission’s destination was no accident: he knew that the queen was Christian and hoped she would be an ally.

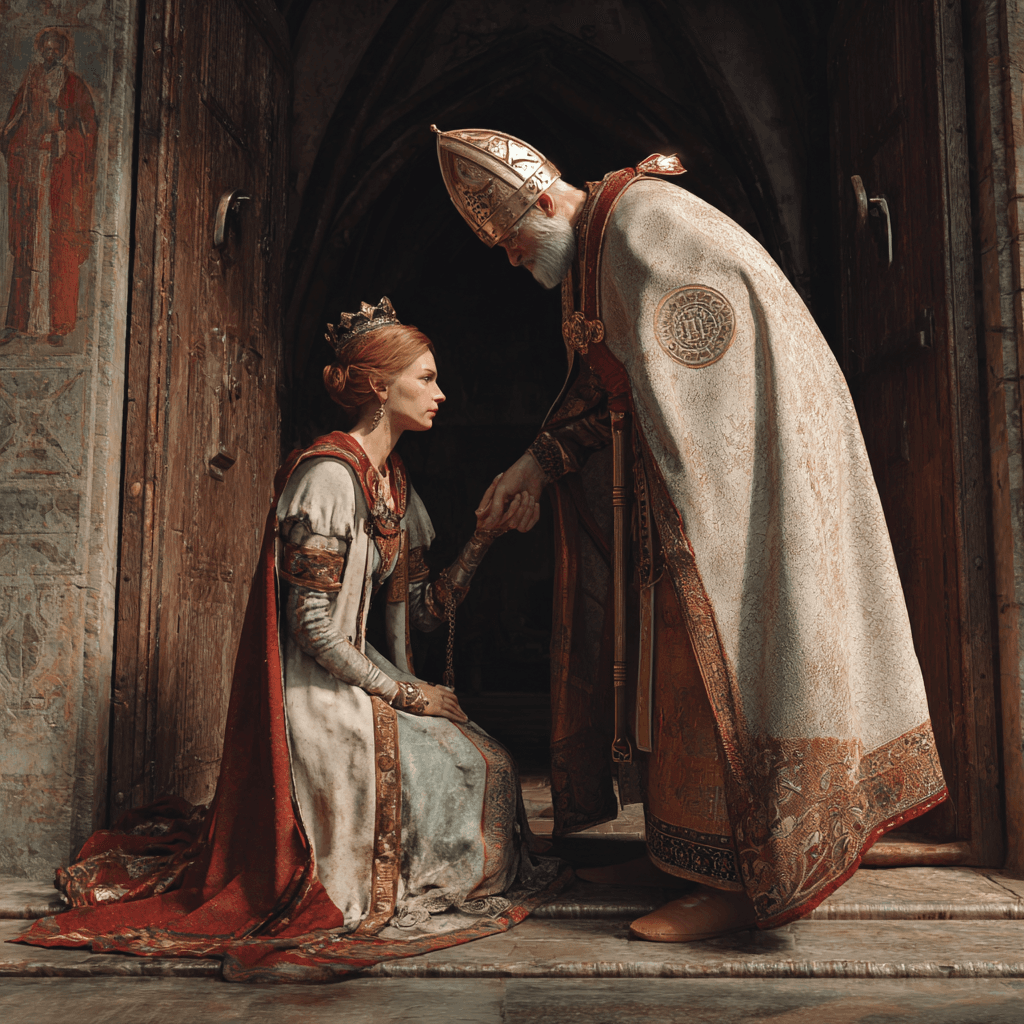

Bertha’s role in the success of the Gregorian mission cannot be overstated. She welcomed Augustine and his companions, providing them with the support and protection they needed in a foreign land. Augustine initially used St Martin’s Church as his base, a testament to Bertha’s foresight in maintaining a Christian place of worship. Without her patronage, it is likely that the mission would have faced far greater obstacles, and the focus of Christian activity might have shifted elsewhere, perhaps to London or York, altering the religious map of England.

Æthelberht’s eventual conversion to Christianity, traditionally dated to Whitsunday 597, was a turning point for the kingdom and for England as a whole. While the king’s motives were undoubtedly complex – ranging from personal conviction to political calculation – Bertha’s influence was a critical factor. Pope Gregory himself wrote to Bertha, praising her faith and urging her to continue guiding her husband and people towards Christianity.

Legacy in Canterbury

The impact of Bertha’s actions is most visible in Canterbury, which became the epicenter of English Christianity. Augustine was appointed the first Archbishop of Canterbury, and the foundations were laid for what would become Canterbury Cathedral and St Augustine’s Abbey. Bertha and Æthelberht’s joint patronage of these institutions ensured that Canterbury would remain the spiritual heart of England for centuries.

Bertha’s legacy is woven into the fabric of the city. The Queningate, a gate in the city wall, is named for the queen, marking the route she would have taken from the royal palace to St Martin’s Church. Statues of Bertha and Æthelberht stand in Lady Wootton’s Green, facing each other as symbols of the partnership that changed English history. Inside St Martin’s, a wooden statue and stained-glass windows commemorate her role as a founder and benefactor.

“It is striking that one who left no writings or speeches, and passed no laws, could have had such a major influence on the city’s importance.”

Family and Descendants

Bertha and Æthelberht had at least two children: Eadbald, who succeeded his father as king of Kent, and Æthelburg (Ethelberga), who became queen of Northumbria and played a key role in the Christianization of that kingdom. Through Æthelburg, Bertha was the grandmother of Saint Eanswythe and great-grandmother of Elflaed, abbess of Whitby, further extending her influence into the next generations of English Christianity.

Eadbald initially resisted Christianity, reverting to paganism after his father’s death, but eventually reconverted, ensuring the survival of the new faith in Kent. This period of uncertainty highlights the fragility of the Christian foothold in early medieval England and the importance of Bertha’s legacy in establishing enduring institutions and traditions.

Death and Historical Memory

The exact date of Bertha’s death is uncertain, with estimates ranging from shortly after 601 to as late as 616. Her passing marked the end of an era, but her influence endured. Medieval chroniclers, including Bede, recognized her significance, though later generations often overlooked her contributions in favor of more prominent male rulers.

Modern Canterbury continues to celebrate Bertha’s achievements. The Bertha Trail, marked by bronze plaques, traces her route through the city, and her story is told in museums, churches, and public spaces. The discovery of a coin bearing the name of her chaplain, Liudhard, near St Martin’s Church, provides tangible evidence of the Christian community she fostered.

Bertha’s Quiet Power

Bertha’s life is a testament to the quiet power of faith, diplomacy, and cultural exchange. She did not wield armies or issue edicts, yet her steadfast commitment to her beliefs and her ability to navigate the complexities of two worlds changed the course of English history. Through her marriage, she brought the light of Christianity to Kent; through her example, she inspired others to follow.

Her story reminds us that history is shaped not only by warriors and kings but also by those who work behind the scenes, building bridges, nurturing communities, and planting seeds that will bear fruit long after they are gone.