The establishment of the Icelandic Althing in 930 CE is a remarkable event in the history of governance and democracy, marking the birth of the world’s oldest surviving parliament. Set against the backdrop of Viking expansion, Iceland’s unique geographic and cultural landscape, and the evolving political structures of medieval Europe, the Althing stands as a symbol of the Icelandic commitment to law, order, and collective decision-making.

The Context of Viking Iceland

In the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Iceland was a relatively isolated land, settled by Norsemen from Norway, Denmark, and other parts of Scandinavia. Iceland’s settlement is traditionally dated to around 870 CE, when the first Norsemen, led by the legendary Norse explorer Ingólfur Arnarson, arrived and began to establish farming communities. Iceland, due to its geographic isolation, lacked centralized political structures, unlike the more established kingdoms of the time in Scandinavia.

The settlers of Iceland were primarily free men, known as “bondi,” who came from a variety of social backgrounds, but who shared a common desire for freedom from the rule of kings and chieftains in their native lands. As the population grew, so did the need for systems of governance to manage disputes, establish laws, and provide order in a land where there were no pre-existing institutions of power. The Icelandic settlers brought with them the traditions of the Althing, a form of assembly and law-making rooted in their Viking heritage, which would ultimately evolve into the Althing of Iceland.

The Role of Law and Custom in Viking Society

In Norse society, law played a central role in maintaining order and mediating disputes. The Norse had a unique system of law, heavily influenced by customary practices. The traditional Norse “thing” (or assembly) was a gathering of free men where legal matters were debated, and decisions were made by consensus. These assemblies were local in nature and were convened at regular intervals to settle disputes, decide on collective actions, and ensure justice within the community.

The “thing” system was rooted in the idea that the collective will of the people would guide the decisions, with an emphasis on consensus rather than strict rule by a single monarch. It was an egalitarian structure that emphasized the participation of all free men in important decisions. These assemblies were often presided over by a designated law speaker, who would recite the law, and the verdicts would be enforced by local chieftains or leaders.

In Iceland, as the population grew and settlements spread across the island, the need for a broader assembly arose. Local “things” could no longer effectively manage the increasingly complex society. Thus, the idea of a central assembly that could bring together representatives from different regions of the island gained traction. This would ultimately become the Althing, a grand council that could legislate on a national scale, unify the various regional laws, and ensure the implementation of justice across the island.

The Establishment of the Althing

The Althing was established in 930 CE by the Icelandic chieftains and leaders as a central legal and legislative body. At its inception, the Althing was intended to serve several purposes. It would function as a legislative body that could create laws for the entire island, an executive body to oversee the enforcement of those laws, and a judicial body to resolve disputes and interpret legal matters. The Althing was held at Thingvellir, a site in Iceland that held great historical and cultural significance. Thingvellir, which translates to “Assembly Plains,” was chosen as the location because of its central position and its natural features that allowed for a large gathering of people. The location also had spiritual significance, as it was believed to be a sacred site by the early Icelandic settlers.

The Althing was organized around a central law speaker, or “lögsögumaður,” who was elected to recite the law to the assembly and preside over the proceedings. The law speaker’s role was crucial in maintaining order and ensuring that the laws were upheld. The Althing was also attended by the Icelandic chieftains, known as “goðar,” who represented various regions of the island and played a significant role in the decision-making process. These chieftains had the power to make laws, resolve disputes, and enforce decisions. The assembly was also attended by the common people, who had the right to present legal matters and seek justice, though their influence on the legislative process was more limited.

The Structure of the Althing

The Althing was unique in that it combined elements of legislative, judicial, and executive powers in one institution. The structure was designed to ensure that all free men in Iceland had a voice in the governance of the island, while also ensuring that decisions were made in an orderly and efficient manner. The Althing operated on the basis of consensus and consultation, rather than a majority rule, reflecting the democratic traditions of Norse society.

One of the key elements of the Althing was the law code, which was recited by the law speaker during the annual gatherings. The law code, known as the “Grágás,” was a compilation of existing laws and customs, and it formed the legal foundation for Icelandic society. The Grágás was not a written document in the modern sense but was instead transmitted orally by the law speaker. It was the responsibility of the law speaker to memorize and recite the laws in front of the assembly, ensuring that everyone was aware of the laws and understood their rights and responsibilities.

In addition to the law speaker, the Althing was composed of a council of chieftains, who were elected by the people to represent the various regions of Iceland. These chieftains were responsible for making decisions on behalf of their communities, and they played a central role in the legislative process. The Althing also had a system of courts, known as “fjórðungar,” which were regional courts that heard legal disputes and enforced the laws passed by the assembly.

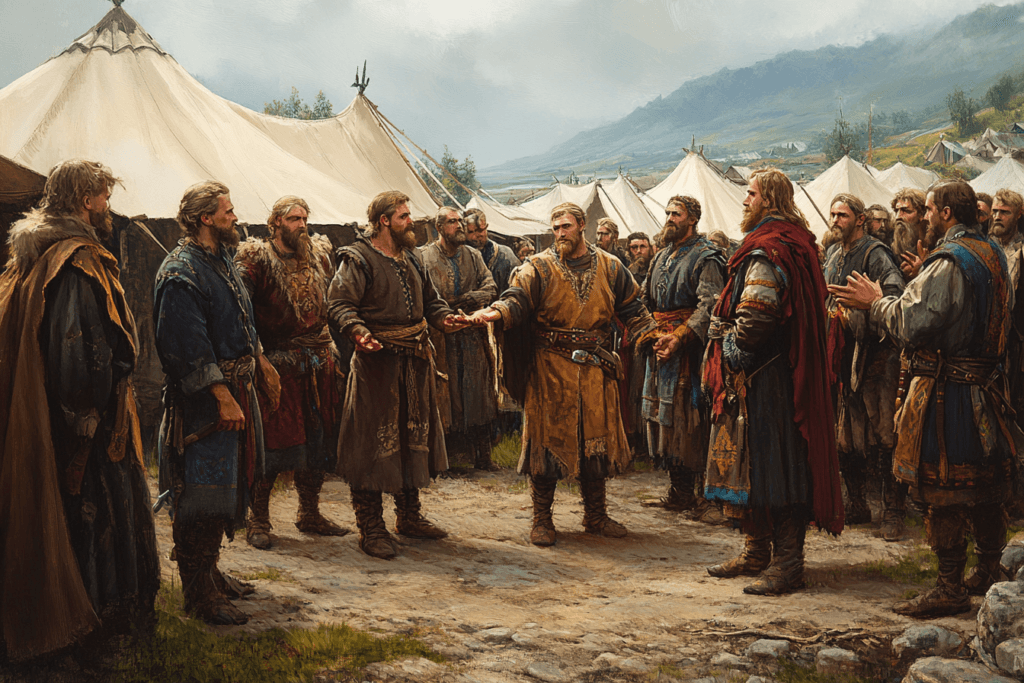

The Althing was held annually, typically during the summer months, and it was an event that brought together Iceland’s leading citizens, as well as common people, who would travel from all over the island to participate. During the two weeks of the Althing a temporary settlement of tents and turf booths would spring up to house participants and their supporters. The gatherings were not only important for political and legal matters but also served as social and cultural events, where people could meet, trade, and exchange news. The Althing was a symbol of Icelandic unity, where diverse voices could be heard and collective decisions were made.

The Role of the Althing in Icelandic Society

The Althing’s role in Icelandic society was multifaceted. It was both a forum for resolving disputes and a legislative body that created and modified laws. It was also a center of social life, where people from different regions of the island could gather and interact. The Althing helped to shape the cultural and political identity of Iceland, fostering a sense of unity and shared purpose among the Icelandic people.

The Althing was crucial in resolving conflicts and ensuring the peaceful coexistence of different communities. The system of laws and courts allowed for disputes to be settled in a fair and orderly manner, reducing the need for violence and blood feuds, which were common in other Viking societies. The Althing also played a key role in maintaining the social hierarchy and the rule of law, as it ensured that even the most powerful chieftains were held accountable to the laws of the land.

Over time, the Althing would continue to evolve, and its influence would expand. However, the core principles of the Althing – democratic participation, legal equality, and consensus decision-making – remained constant throughout its history. These principles laid the foundation for the Icelandic Republic that would later emerge in the 20th century, demonstrating the lasting impact of the Althing on Icelandic governance.