In the shadow of modern skyscrapers, overlooking the slow grey flow of the Thames, stands a building that once defined royal power and fear itself: the Tower of London. It was conceived as a fortress of conquest: a Norman fist clenched around a newly-subdued city. The Tower of London began as a symbol of a foreign king’s determination to hold what he had seized by blood.

The Norman Conquest and the Seeds of Stone

The date was 1066. William, Duke of Normandy, had defeated King Harold at Hastings, earning the crown of England through conquest – a victory that left him both ruler and foreigner in a hostile land. London, the largest and wealthiest city in the kingdom, submitted peacefully that winter, but William was no fool. Submission could change as swiftly as the tide. To secure his crown, he needed stone, soldiers, and fear.

Like all Norman conquerors, William understood the architecture of dominance. Across England his commanders raised motte-and-bailey castles: simple but effective wooden structures elevated on earthen mounds, ringed by palisades and ditches. They could be built in weeks and served as both military bases and emblems of Norman command. Yet London needed something greater. The king’s eye turned to the eastern edge of the city, near where the Roman walls still loomed, relics from an empire long dead. It was here, beside the Thames, that William ordered the construction of a permanent fortress – the Tower of London.

Bishop Gundulf and the White Tower

The first stone of what would become the Tower was laid around 1078, a decade after the Conquest. To oversee its construction, William appointed one of his most trusted men: Bishop Gundulf of Rochester. Gundulf was a monk of remarkable skill, part warrior-engineer, part visionary architect. His work fused Romanesque solidity with Norman ambition. Where Saxon builders had favored timber, Gundulf raised England’s future in stone.

The heart of his design was the massive keep later known as the White Tower. Rectangular and unyielding, it dominated not only the skyline but the psychology of those who saw it. At 90 feet high with walls up to 15 feet thick, its presence alone could cow the city below. The keep was originally built from stone imported from Normandy, a costly statement of authority, and completed with local Kentish ragstone. Its corners were reinforced, its windows narrow and defensive, its gateway protected by wooden drawbridges leading to fortified towers. The message was unmistakable: the Normans had come not merely to rule but to remain.

Inside, the White Tower served both as armed refuge and royal residence. The great hall at its center was the seat of royal justice and ceremony, while chapels like St. John’s offered a touch of sanctity amid the architecture of domination. But the keep’s greatest strength was psychological. From the city walls or across the river, Londoners could always see the towering reminder of their new masters – an enduring Norman shadow.

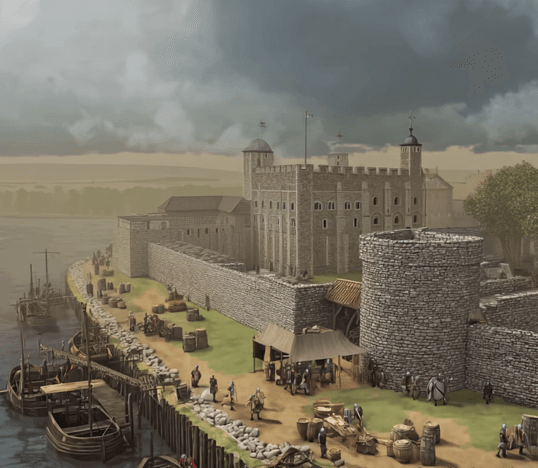

The Tower and the Thames

The strategic placement of the Tower beside the Thames was more than symbolic. Control of the river meant control of trade and communication. The fortress linked London to the sea, allowing supplies, men, and messages to flow directly to Normandy. A riverside postern gate, later known as Traitors’ Gate, gave discreet entry from the water – centuries later, prisoners would curse that same route as they entered, never to return.

From its very birth, the Tower was not only a bastion of defense but a nexus of royal logistics. It was a treasury, an armory, and a stronghold against rebellion. Though its walls silenced many shouts of defiance, London never truly forgot that the Tower was raised not in trust, but in conquest.

From William to Rufus: Consolidating the Fortress

William the Conqueror did not live to see the Tower completed. His son, William II – known as Rufus – continued the work during his own reign (1087–1100). To him fell the task of strengthening the great keep and improving its defensive perimeter. It is during Rufus’s time that the Tower likely acquired its first surrounding curtain wall and ditch – still modest, but sufficient to transform the building from an isolated keep into a true citadel.

The White Tower’s looming height and pristine whitewashed stone soon gave it its enduring name. Chroniclers of the 12th century already spoke of it as a landmark recognized across England, its brightness gleaming in the morning sun as ships drifted up the river. Even in its earliest form, visitors compared it to the greatest fortresses of Europe.

But the Tower also became a royal symbol not just of strength, but of suspicion. William and his sons ruled a kingdom divided by language, loyalty, and resentment. The Tower’s existence reminded the English that Norman rule rested not only on divine right, but on architectural might.

The Tower Under Henry I and Stephen

Henry I, the youngest son of the Conqueror, succeeded William Rufus in 1100. His reign marked the Tower’s gradual transformation from fortress to functioning royal palace. Henry established within its walls a treasury and archive, reflecting the growing administrative sophistication of Norman England. Charters, writs, and financial records were stored behind its stone defenses – a recognition that paper, too, could be power.

It was also under Henry I that the Tower gained more domestic furnishings and royal comforts. Great halls became grander; chapels more ornate. Yet even as the Tower took on the trappings of domesticity, it remained the stark emblem of royal might. Its keep served as refuge in times of unrest, most famously during the chaos following Henry’s death in 1135.

When Henry’s daughter Matilda and his nephew Stephen clashed for the throne, a civil war known as The Anarchy erupted. London became a center of shifting loyalties. In this turbulent time, the Tower’s strategic position was both prize and sanctuary. Whoever held the Tower held the heart of the capital. Stephen seized it early in his reign, and his defiance in maintaining control of the fortress, even while losing faith elsewhere, attested to its unparalleled importance. Londoners often found themselves forced to choose sides not by conviction, but by whichever army controlled the Tower’s gates.

Henry II and the First Great Expansion

Following the end of The Anarchy and the accession of Henry II in 1154, England entered a period of rebuilding. Henry, founder of the Angevin dynasty, understood both symbolism and necessity. The Tower was rebuilt and extended to match the growing scale of his empire. By the 1170s, Henry had strengthened its defenses and improved its chambers, but perhaps more importantly, he institutionalized its role within royal governance. It became a central storehouse for arms, regalia, and royal documents – a crown’s heart encased in stone.

Henry’s reign also marks the beginning of a tradition that would define the Tower’s darker reputation: imprisonment. Though originally designed as a fortress and royal home, its secure walls made it an ideal prison for high-ranking captives. The first recorded prisoner, Ranulf Flambard, Bishop of Durham, was held there by Henry I for embezzlement; his unlikely escape by rope hidden in a wine cask would become legendary. Under Henry II and his successors, the Tower would begin to fill with the unfortunate, the treacherous, and the politically inconvenient.

Richard the Lionheart and Hubert de Burgh

Richard I, or the Lionheart, spent little time in England, his heart and fortune consumed by the Crusades. Yet it was under his reign that major fortification work resumed at the Tower. Between 1189 and 1199, his regent, William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely, oversaw extensive enhancements, including the creation of a stronger defensive ditch and the beginnings of an outer curtain wall.

Richard’s successor, King John, lost Normandy but strengthened his hold on England’s institutions. During his troubled reign, the Tower again became a symbol of royal authority besieged. When John’s barons rebelled, seizing London in 1214, they forced his men to surrender the Tower. For the first time since its founding, the fortress fell into hostile hands. That humiliation would not be forgotten.

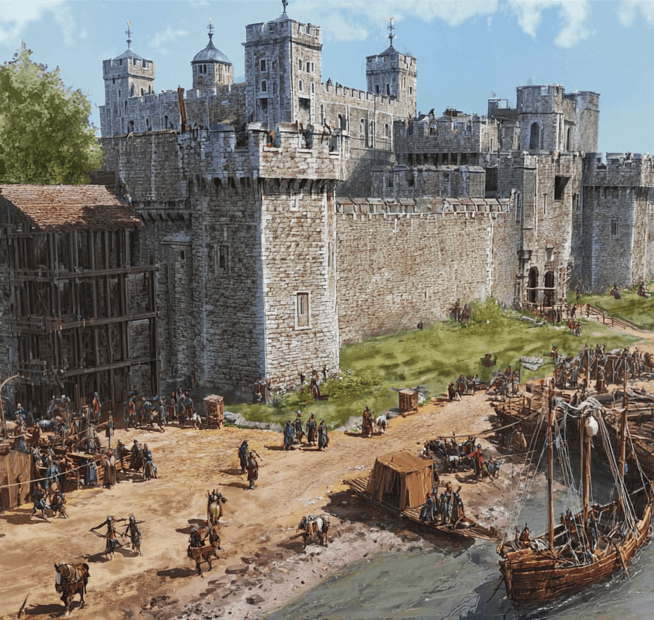

Under Henry III, John’s son, renewal became both necessity and obsession. The young king ordered massive reconstruction of the Tower’s defenses, creating the concentric system that endures to this day. The outer curtain wall, completed between 1238 and 1240, introduced new guard towers – Wakefield, Beauchamp, and Devereux among them – each commanding a strategic angle. The moat was deepened and connected to the Thames, transforming the Tower into an island fortress.

But Henry was also a builder of beauty. He adorned the royal apartments with elaborate decorations and rebuilt St. Peter ad Vincula, the parish church within the Tower’s precincts. He transformed the grim fortress into a palace worthy of a king, though always surrounded by walls thick enough to withstand rebellion.

The Tower as Palace and Prison

By the mid-13th century, the Tower had evolved from solitary keep to royal complex – a labyrinth of halls, towers, gates, and walls linked by courtyards and bridges. When Henry III’s son, Edward I, came to power in 1272, he found a structure already rich in history and function. Yet Edward was a perfectionist; no fortress could be too strong, no palace too grand. He widened the moat, reinforced the bell tower, added the outer barbican known as the Lion Tower (where exotic beasts were kept), and sealed the Tower’s role as both military stronghold and royal residence.

It was under Edward that the Tower truly earned its reputation as the seat of authority – and fear. The royal mint operated within its walls; foreign envoys were received in its halls. But it also became the place where power’s victims were confined. Even in these early centuries, English nobles learned that the Tower’s gates could open to anyone, but its walls often closed behind those who had offended the crown.

Early Intrigue and Rebellion

The Tower’s early centuries were marked by periodic rebellion and siege. In 1191, during Richard’s reign, rival factions stormed the Tower to challenge his chancellor. In 1216, during the turmoil of the barons’ wars, Londoners again broke its hold. Yet by the reign of Edward I and Edward II, no rebellion could take London without first taking the Tower.

In 1327, when Edward II was deposed, his wife Queen Isabella and her ally Roger Mortimer took refuge inside the Tower, proclaiming Edward III king. The young monarch’s coronation the following year took place in Westminster, but his first night as king had been spent in the White Tower. Generations of monarchs would follow that pattern: before their coronation, they would rest within the Tower’s walls as a symbolic gesture of preparation and power. The fortress, born in conquest, had become woven into the rituals of monarchy itself.

The Tower and the City

The relationship between the Tower and the citizens of London was always tense, even adversarial. The fortress represented royal dominance over a city fiercely protective of its liberties. Londoners both feared and resented their neighbor, whose garrison could threaten them more easily than protect them. The Tower’s constable often found himself not just a military commander but a political diplomat, balancing royal authority with urban pride. At times, open hostility flared, especially when the Tower’s soldiers clashed with townsfolk over jurisdiction or taxes.

Yet the Tower also contributed to the city’s prosperity. Craftsmen, masons, and merchants profited from its endless need for maintenance. Its role as an arsenal and treasury drew scholars, clerks, and specialists in royal service. Even the animals kept in the Lion Tower – gifts from foreign rulers – became a kind of early royal menagerie, attracting visitors long before tourism was invented.

Architectural Might and Symbolic Power

By the end of the 13th century, the Tower of London had achieved its essential form: a concentric fortress enclosing centuries of fear, ambition, and history. The White Tower still stood at its core, stark and commanding as it had been under William the Conqueror, but now surrounded by layers of stone: inner and outer curtain walls, each bristling with towers bearing noble names. The Thames lapped against its quay, boats came and went beneath the Byward and Traitors’ Gates, and sentries paced along battlements once raised against rebellion.

To the casual observer, the Tower was impregnable. But its real strength lay not just in its walls but in what it represented: the unbroken continuity of royal authority. Every monarch added to it, reshaped it, or used it according to the times. From William’s original fortress of domination had grown the kingdom’s heart of governance and fear, a place where power was built literally into the stone.

Legacy of the Founding Centuries

Long before its notoriety as a prison for queens and traitors, the Tower served a nobler, if still fearsome, purpose: to guard the realm, to protect the crown jewels and royal treasure, and to project the king’s invincibility. The men who walked its halls in the 11th and 12th centuries – Norman knights, bishops, masons, and kings – could hardly imagine the centuries of drama that these stones would later witness.

The fortress that once stood as the ultimate tool of conquest would one day hold within its chambers queens, princes, and political martyrs. Yet those future tragedies owe their setting to the ambitions of William and Gundulf – the builder-king and his bishop – who, in the turbulent wake of 1066, dreamed of a fortress that no subject could challenge.

More than nine centuries later, the Tower of London still tells their story. Its white stones glint above the river, its ravens still circle its battlements, and its presence still commands respect. Born out of invasion, it became the spine of English monarchy: part palace, part prison, and always, a monument to the will to rule.