The Empress Who Shaped Byzantine History

Early Life and Rise to Power

Irene’s origins were humble by imperial standards. Born to a noble Greek family in Athens, her beauty and intelligence caught the attention of Emperor Constantine V, who chose her as a bride for his son and heir, Leo IV, in 768. This marriage catapulted the young Athenian into the heart of imperial politics, a realm she would come to dominate through cunning and determination.

In 775, Leo IV ascended to the throne, making Irene the empress consort. However, her position was precarious. The imperial court was deeply divided over the issue of iconoclasm – the destruction of religious images – which had been imperial policy for decades. Irene, an iconophile who supported the veneration of icons, found herself at odds with her husband’s iconoclastic stance.

Regent and Co-Ruler

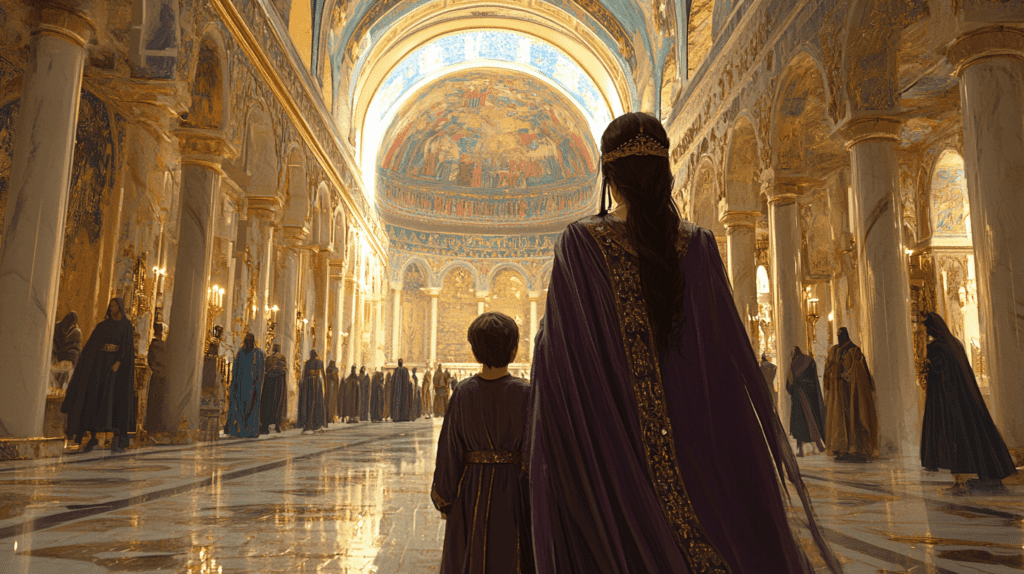

Irene’s fortunes changed dramatically in 780 when Leo IV died unexpectedly, leaving their nine-year-old son, Constantine VI, as emperor. As his mother and guardian, Irene became regent, effectively ruling the empire. She quickly moved to consolidate her power, crushing a conspiracy by her brothers-in-law and replacing key military commanders with her own supporters.

During her regency, Irene displayed remarkable political acumen. She negotiated with both Charlemagne and Harun al-Rashid, two of the most powerful rulers of her time, demonstrating her diplomatic skills on the international stage. However, it was in the realm of religious policy that Irene would make her most lasting impact.

The Second Council of Nicaea

In 787, Irene convened the Second Council of Nicaea, a watershed moment in Byzantine history. This council reversed the iconoclastic policies of previous emperors, restoring the veneration of icons in the Orthodox Church. This decision not only ended a period of intense religious conflict but also realigned the Byzantine Empire with the papacy in Rome, temporarily healing the rift between Eastern and Western Christianity.

Irene’s motivations for this dramatic policy shift were likely a combination of personal religious conviction and political calculation. By championing the iconophile cause, she gained the support of the powerful monastic faction and much of the general population, who had never fully embraced iconoclasm.

Conflict with Constantine VI

As Constantine VI approached adulthood, tensions grew between mother and son. In 790, a military revolt briefly deposed Irene, proclaiming Constantine VI as sole ruler. However, Irene’s political skills allowed her to regain her position as co-ruler in 792.

The relationship between Irene and Constantine deteriorated further over the next few years. In a shocking move that would forever tarnish her legacy, Irene orchestrated a plot against her own son in 797. Constantine was seized, blinded, and imprisoned on her orders. This brutal act effectively ended his reign and likely his life, though the exact date of his death is unknown.

Sole Ruler of the Byzantine Empire

With Constantine out of the way, Irene proclaimed herself basileus (emperor), adopting the male title rather than the feminine basilissa (empress). This unprecedented move made her the first woman to rule the Byzantine Empire in her own right.

Irene’s solo reign was marked by both achievements and challenges. She continued to support the Orthodox Church and the monastic community, earning her veneration as a saint in the Greek Orthodox tradition. However, her rule also saw military setbacks and economic difficulties.

One of the most intriguing episodes of Irene’s reign was the proposed marriage alliance with Charlemagne, the powerful Frankish king who had been crowned Emperor of the Romans by the Pope in 800. This potential union could have reunited the Eastern and Western halves of the old Roman Empire, dramatically altering the course of European history. However, the plan never materialized, possibly due to opposition from Irene’s court.

Downfall and Legacy

Despite her political savvy, Irene’s hold on power proved tenuous. In 802, a conspiracy of officials and generals, concerned about her financial management and possibly her gender, deposed her. Nikephoros, her finance minister, was crowned emperor, and Irene was exiled to the island of Lesbos, where she died the following year.

Irene’s legacy is complex and often contradictory. She is remembered as both a ruthless political operator willing to blind her own son for power, and as a pious ruler who restored Orthodox doctrine. Her reign marked a crucial turning point in Byzantine history, ending the Isaurian dynasty and paving the way for the Macedonian Renaissance of the 9th and 10th centuries.

Historical Significance

Irene’s rule had far-reaching consequences beyond her lifetime:

Religious Impact: Her reversal of iconoclasm profoundly shaped Orthodox Christianity, influencing religious art and practice to this day.

Political Precedent: As the first woman to rule Byzantium in her own right, Irene set a precedent that would be followed by later empresses like Theodora and Zoe.

Western Relations: Her reign indirectly contributed to the coronation of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor, as the Pope used the presence of a woman on the Byzantine throne as justification for this momentous act.

Conclusion

Irene of Athens remains one of the most fascinating figures in Byzantine history. Her rise from obscure origins to imperial power, her role in ending iconoclasm, and her unprecedented position as a female ruler all mark her as a truly remarkable historical figure. While her methods were often ruthless, her impact on Byzantine religion, politics, and culture was undeniable and long-lasting.

Irene’s story serves as a compelling reminder of the complex interplay between personal ambition, political necessity, and religious conviction in shaping history. It also highlights the exceptional circumstances under which women could attain and wield power in medieval societies. Whether viewed as a cunning usurper or a pious defender of orthodoxy, Irene of Athens undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the Byzantine Empire and the broader sweep of medieval history.