Odo of Bayeux, born around 1035, was a unique and larger-than-life character of the 11th century. As the half-brother of William the Conqueror, Odo held a powerful place in Norman and later English politics, blending the roles of bishop, warrior, ruler, and patron of the arts with great ambition and occasional ruthlessness.

Rise to Power

Odo was the son of Herleva of Falaise and Herluin de Conteville. His mother Herleva was also the mother of William the Conqueror by Duke Robert I of Normandy, making Odo William’s maternal half-brother. From an early age, Odo enjoyed the privileges of his noble birth and his close relationship with William. In an unusual move for the time, William appointed Odo bishop of Bayeux in Normandy in 1049, when Odo was still a teenage boy.

Despite his youth, Odo quickly established himself as both a capable church leader and a figure with secular influence. Chroniclers from the period praised his eloquence, prudence, and generosity. He was ambitious, well-educated, and connected, qualities that served him well in the volatile world of Norman politics.

Role in the Norman Conquest of England

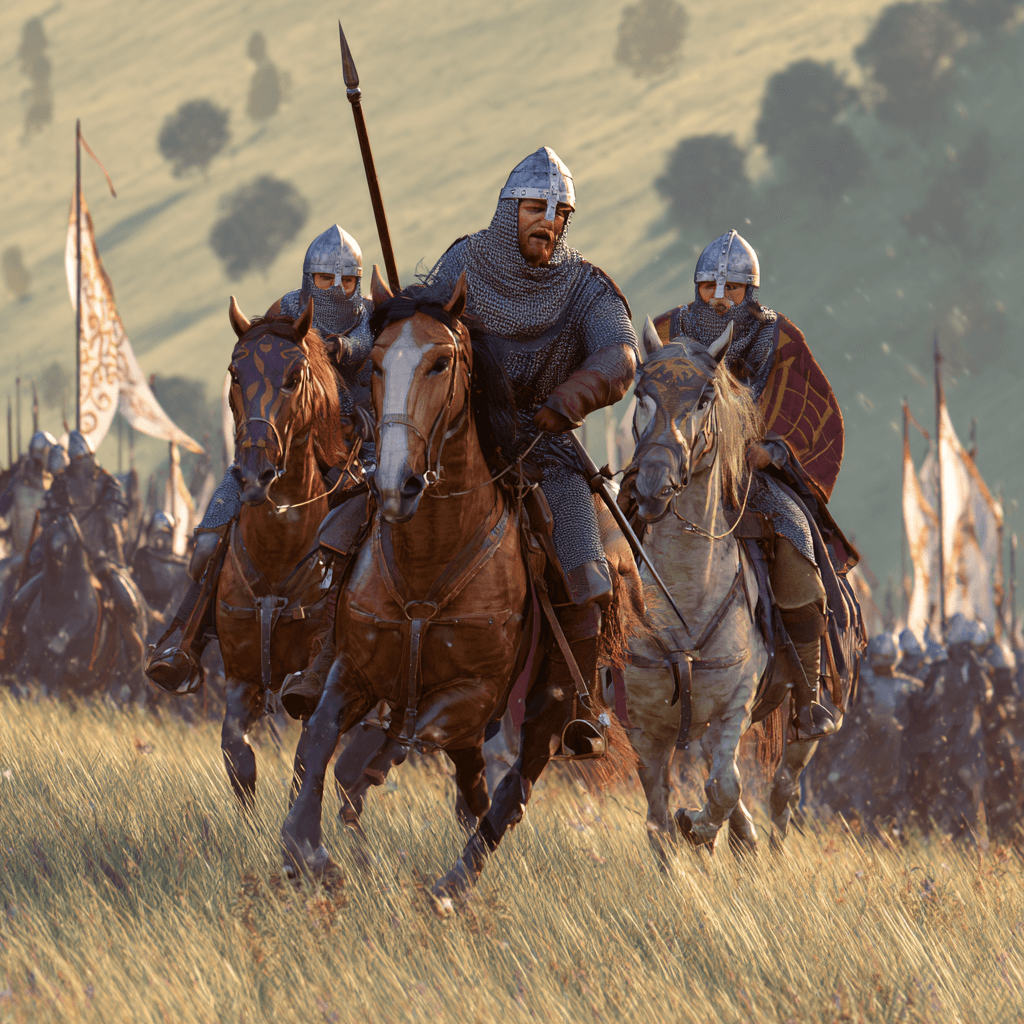

Odo played a critical role in the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. He was one of the key Norman leaders who supported William in his claim to the English throne, and it is believed he contributed significantly to the invasion fleet. At the pivotal Battle of Hastings, Odo not only fought but also served as a battlefield commander, often rallying Norman troops under his banner and standing out as a warrior bishop wielding a mace, a symbol of his dual secular and ecclesiastical authority.

After the victory, William rewarded Odo handsomely with land and title. Odo was made Earl of Kent, given the strategic castle at Dover, and granted estates in multiple English counties, eventually becoming the richest tenant-in-chief in England after the king himself. Such wealth gave him immense influence and positioned him as the second most powerful man in England during much of William’s reign.

Additionally, Odo was appointed regent of England, governing the kingdom whenever William returned to Normandy. This entrusted him with considerable authority, dealing with internal rebellions, border conflicts, and administration.

Patron of the Bayeux Tapestry

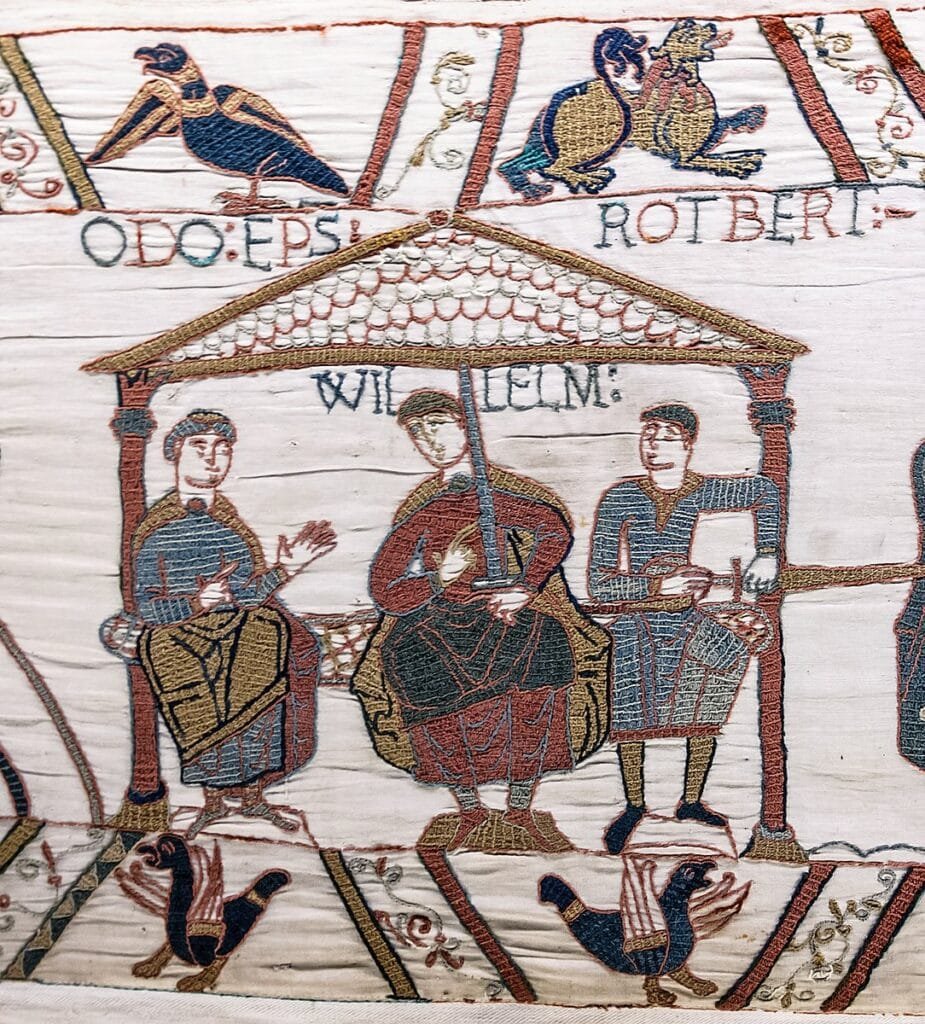

One of Odo’s lasting legacies is the probable commissioning of the Bayeux Tapestry, an extraordinary embroidered work that visually narrates the Norman conquest of England. Created between 1067 and 1079, the tapestry prominently features Odo alongside William, highlighting his prominent role and influence. It was likely made for the dedication of Bayeux Cathedral, which Odo helped rebuild and embellish.

The tapestry’s dramatic scenes and lavish detail make it not only an artistic masterpiece but also a powerful piece of Norman propaganda. Odo is portrayed as a warrior leader encouraging troops, cementing the image of his significance in Norman victory and rule.

Controversies and Downfall

Odo’s life was equally marked by controversy and conflict. Despite his ecclesiastical position, he was accused of secular excesses including land grabbing and exploitation. In 1076, William the Conqueror brought him to trial, charging him with fraud and the illegal confiscation of church property.

Tensions grew over the years, and in 1082, Odo fell from royal favor. William imprisoned him in Rouen for raising an army without permission, supposedly intending to support his own candidacy for the papacy in Rome. This ambitious overreach was seen as a direct challenge to William’s authority. Odo remained imprisoned for several years but retained most of his lands.

Upon William’s death in 1087, Odo was released by the new king, William II. However, Odo then took part in a rebellion to reclaim his lost privileges alongside Robert Curthose, William’s eldest son and duke of Normandy. The rebellion burst forth like a storm long held behind stone walls. In the spring of discontent, Odo resolved to throw his weight behind Robert Curthose, the restless Duke whose grievances could ignite all of Normandy and beyond. The alliance was not born of loyalty but of shared frustration, and together, they moved against the authority that bound them.

Rebellion

Their cause gathered momentum as disaffected knights and lords drifted toward it. Men weary of obedience, hungry for spoils or recognition, found common cause in rebellion. Soon, messengers rode across the Channel, carrying promises to those who would join them. Odo’s tongue was sharper than any sword he could wield, and his rhetoric transformed hesitation into zeal. He spoke of liberty where others spoke of treason, of destiny where others whispered doom.

Odo commanded not as a warrior but as an orchestrator, his strategies shaped more by calculation than courage. His counsel urged boldness, swift strikes, relentless movement, the seizing of fortresses before royal forces could gather. Robert, ever gallant, led from the front with reckless heart, his charisma pulling supporters forward even as fate tilted against him.

The rebellion’s early days shone with promise. Several castles fell, garrisons fled, and the royal cause seemed uncertain. For a fleeting moment, Odo’s gamble appeared justified. Yet rebellion seldom endures the weight of its own success. Fractures appeared where unity once stood; greed rubbed shoulders with distrust. Odo’s bitter pragmatism clashed with Robert’s romantic valor. Each sought victory, but neither could steer the tempest they had unleashed.

Royal reprisals struck hard and fast. Troops loyal to authority moved with ruthless efficiency, reclaiming strongholds one after another. Odo’s supporters, seeing the tide turn, began to melt away. What had started as a grand rising descended into confusion and retreat. The dream of defiance collapsed not in one glorious battle but in scattered defeats and exhausted truces.

Odo’s fortunes broke as sharply as they had risen. Captured and condemned, he faced not the glory he had promised his followers but the humiliation of chains. Robert’s idealism, too, crumbled under the harsh glare of defeat. The rebellion that was meant to remake their world left them both diminished – one imprisoned, the other estranged from power once more.

Later Years and Death

Odo’s final chapter saw him become involved in the early crusading movement. He was present at the Council of Clermont in 1095, where Pope Urban II called for the First Crusade. Odo joined the crusader army led by Robert Curthose in 1096, traveling towards the Holy Land.

However, Odo did not reach Jerusalem. He died in early 1097 while visiting Palermo in Sicily, a friend’s court, and was buried in the Palermo Cathedral. Despite never marrying, Odo had a son named John, who later became chaplain to King Henry I.

Character and Legacy

Odo’s personality was as complex as his career. He was described by contemporary chroniclers both as a generous, effective ruler and as ruthless and extravagant. He embodied the Norman warrior-bishop archetype, mixing spiritual duty with military and political ambition. His life reflected the turbulent nature of 11th-century Europe, where power was often seized by force and blended with religious authority.

Odo’s patronage of art and learning alongside his political maneuvers left a distinct mark on Norman and English history. The Bayeux Tapestry remains a vital historical artifact, providing insight into the Norman view of conquest and kingdom-building, with Odo forever pictured among its vivid scenes.