In the tumultuous 7th century, as Anglo-Saxon kingdoms vied for supremacy in Britain, one figure emerged as a beacon of Christian leadership and military prowess: Oswald of Northumbria. Born around 604 CE, Oswald’s life was marked by exile, triumphant return, and ultimately, martyrdom. His reign, though brief, left an indelible mark on English history and the spread of Christianity in the British Isles.

Early Life and Exile

Oswald was born into royalty as the son of Æthelfrith, the powerful king of Bernicia, and Acha of Deira. Bernicia and Deira were the two separate kingdoms that made up Northumbria. His early years were spent in the halls of power, but this idyllic childhood was shattered in 616 when Edwin of Deira, Oswald’s maternal uncle, defeated and killed Æthelfrith near the River Idle. This pivotal event forced the young Oswald into exile, a period that would shape his future and set the stage for his eventual return.

During his time in exile, Oswald found refuge among the Gaels of Dál Riata, a kingdom straddling parts of Scotland and Ireland. It was here, in the monastery of Iona, that Oswald was introduced to Celtic Christianity, an influence that would profoundly shape his later reign. The years spent away from Northumbria were not idle; Oswald honed his military skills and cultivated alliances that would prove crucial in his bid to reclaim his father’s throne.

The Battle of Heavenfield: A Miraculous Victory

Oswald’s opportunity to return came in 633 CE, following a period of chaos in Northumbria. Edwin, who had ruled as a powerful overlord, was killed at the Battle of Hatfield Chase by an alliance between Cadwallon ap Cadfan of Gwynedd and Penda of Mercia. In the aftermath, Northumbria split into its constituent kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira. Oswald’s elder half-brother, Eanfrith, briefly claimed Bernicia but was killed by Cadwallon in 634 while attempting to negotiate peace.

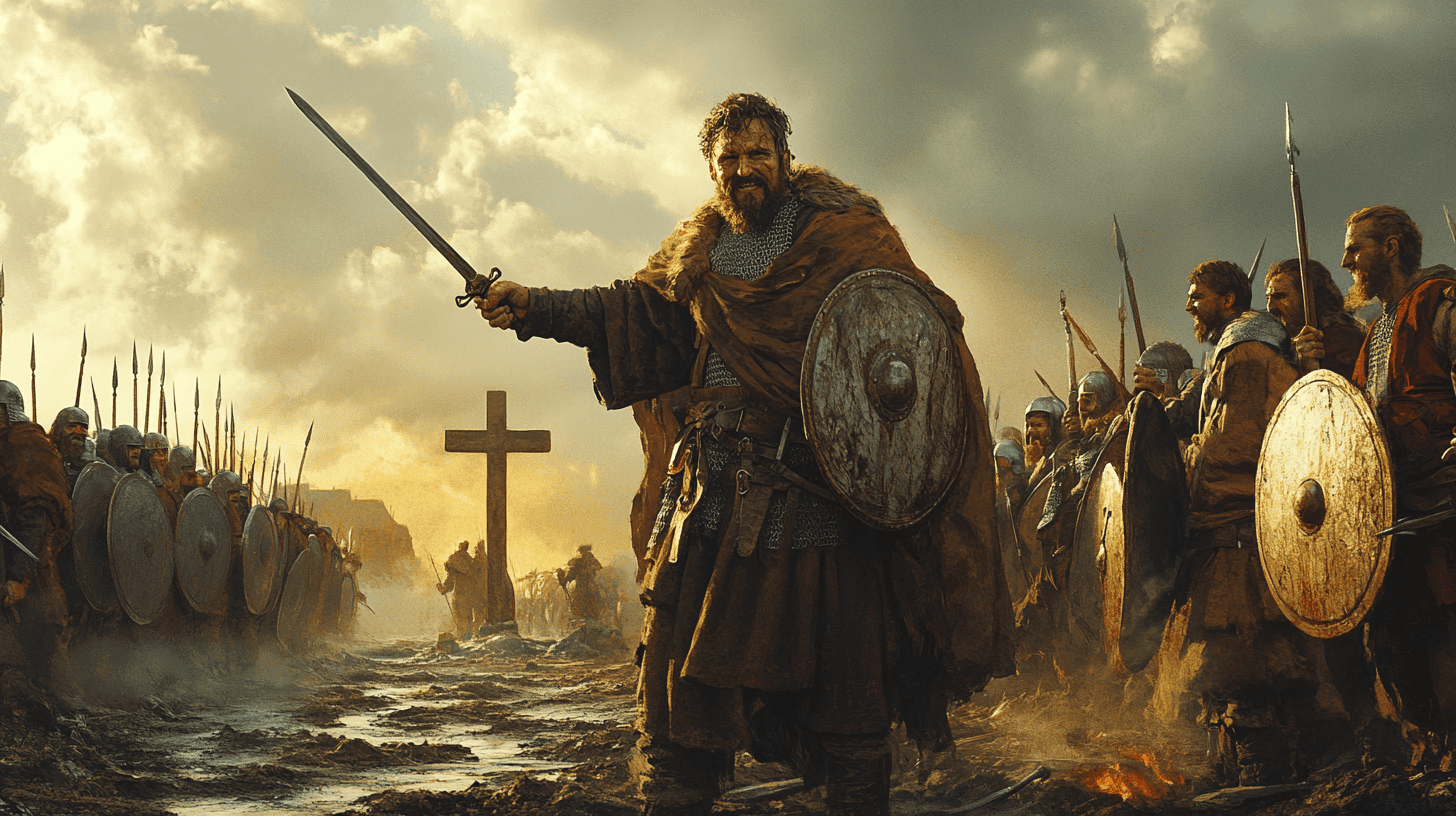

With Northumbria in disarray and under the brutal occupation of Cadwallon, Oswald saw his chance. He gathered an army, drawing support from exiled Bernician nobles and possibly allies from the Kingdom of Rheged. The stage was set for a confrontation that would become legendary: the Battle of Heavenfield.

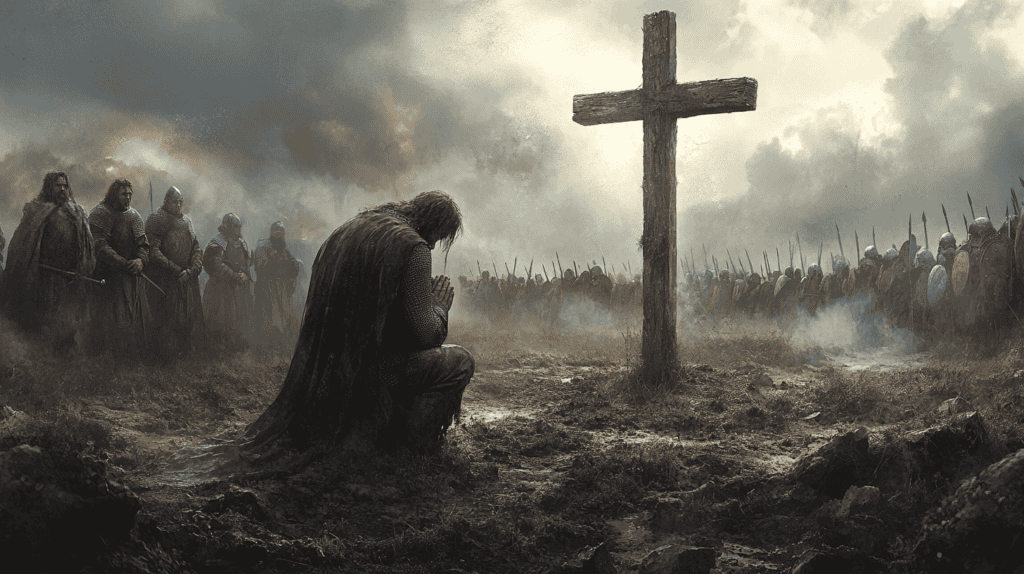

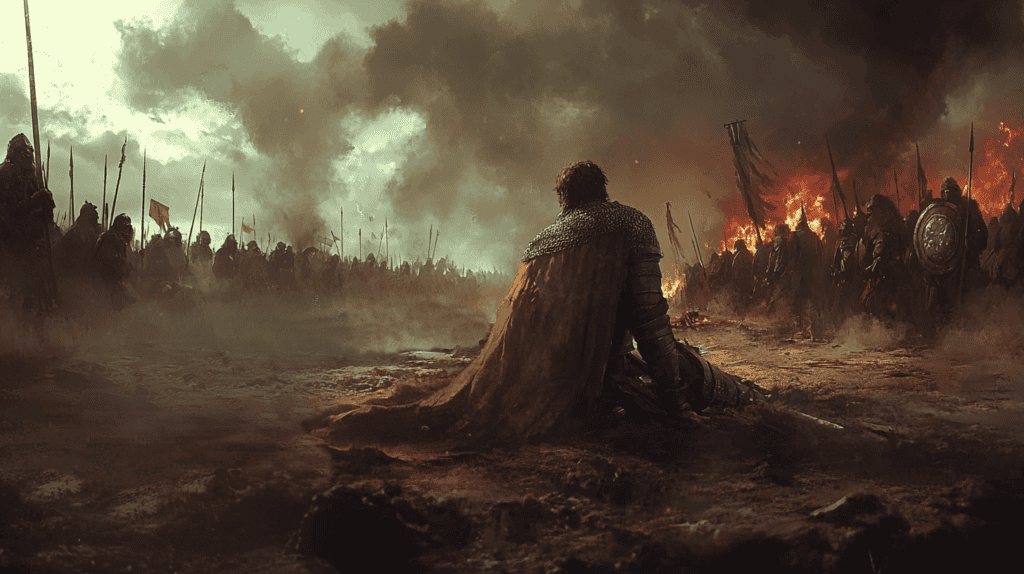

As Oswald’s forces approached Cadwallon’s camp near Hexham, along Hadrian’s Wall, the Northumbrian prince faced a daunting challenge. His army was vastly outnumbered, with perhaps only a few hundred men against Cadwallon’s larger Welsh force. On the eve of battle, Oswald made a decision that would define his reign and his legacy.

In a display of faith that captured the imagination of chroniclers, Oswald erected a wooden cross on the battlefield. Kneeling before it, he led his men in prayer, asking for divine intervention. This act, recorded by the Venerable Bede, became a powerful symbol of Oswald’s Christian leadership.

The battle itself, while shrouded in the mists of history, appears to have been a masterclass in tactical surprise. Oswald’s smaller force likely caught Cadwallon’s army unawares in the early morning. The ensuing combat was swift and decisive. Despite their numerical disadvantage, Oswald’s men routed the Welsh, driving them in panic towards the nearby river known as Devil’s Water. It was here, trapped against the water’s edge, that Cadwallon met his end.

The victory at Heavenfield was more than just a military triumph; it was seen as a divine validation of Oswald’s rule and his faith. The battle site, subsequently known as Heavenfield, became a place of pilgrimage, cementing Oswald’s reputation as a warrior blessed by God.

Reign and Expansion

With Cadwallon defeated and his challengers eliminated, Oswald ascended to the throne of a reunited Northumbria in 634 CE. His reign marked a golden age for the kingdom, as Oswald expanded his influence far beyond the borders of Bernicia and Deira.

Under Oswald’s rule, Northumbria became the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, with the king recognized as the Bretwalda or overlord of Britain. His authority extended across much of modern-day England, Wales, and southern Scotland. This expansion was not merely political; Oswald was equally committed to spreading Christianity throughout his domains.

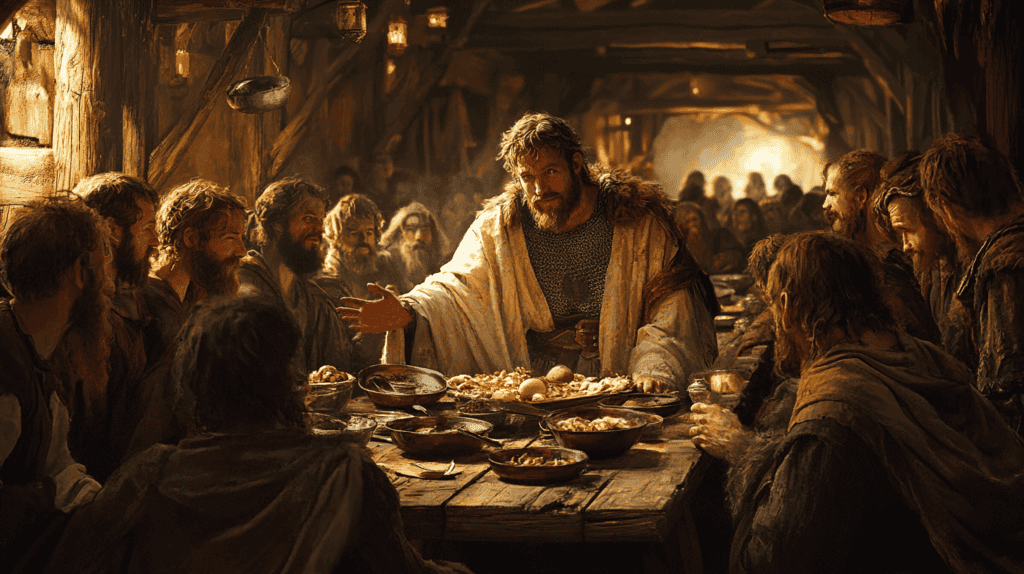

Remembering his time in Iona, Oswald sent for missionaries to convert his people. When the first preacher failed due to his harsh approach, Oswald turned to Aidan, a monk whose gentle methods proved far more effective. In a touching display of humility and dedication, Oswald often acted as interpreter for Aidan, who initially did not speak the Anglo-Saxon language.

Oswald’s commitment to Christianity was not limited to spiritual matters. He was known for his generosity to the poor, a trait that earned him high praise from Bede. One famous anecdote recounts how Oswald, during an Easter feast, gave away all the food and even the silver dishes to the hungry crowds outside his hall.

The Battle of Maserfield: Oswald’s Last Stand

Despite his successes, Oswald’s reign was not without challenges. The greatest threat came from Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, who had been part of the alliance that defeated Edwin years earlier. In 642 CE, tensions between Northumbria and Mercia erupted into open warfare.

The two armies met at Maserfield, near the present-day town of Oswestry in Shropshire. The location suggests that Oswald may have been on the offensive, pushing into territory controlled by Penda or his Welsh allies. This battle would prove to be Oswald’s last.

Details of the battle are scarce, but it’s clear that it was a fierce and bloody affair. Oswald, despite his previous successes, found himself outmatched. In the chaos of combat, the Northumbrian king fell, fighting to the last.

Penda, true to his pagan beliefs, treated Oswald’s body with particular brutality. The fallen king was dismembered, his head and limbs displayed on stakes as a sacrifice to the god Odin. This grisly act, intended as a final humiliation, instead contributed to Oswald’s veneration as a martyr.

Legacy and Sainthood

Oswald’s death at Maserfield marked the end of his eight-year reign, but it was far from the end of his influence. In the years that followed, a cult grew around the fallen king, venerating him as a saint and martyr.

Oswald’s remains became holy relics, believed to possess miraculous powers. His head was recovered and eventually interred at Lindisfarne, later finding its way to Durham Cathedral. Other relics were scattered across Europe, spreading Oswald’s cult far beyond the borders of Northumbria.

The manner of Oswald’s death, combined with his reputation for piety and generosity, cemented his status as a Christian hero. He became a symbol of righteous kingship, a model for future monarchs to emulate. Churches were dedicated to him, and his feast day on August 5th was widely celebrated.