Pepin the Short, also known as Pepin III or Pippin, was a pivotal figure in Frankish history who laid the foundation for the Carolingian dynasty and significantly shaped the political landscape of medieval Europe. Born around 714 in Jupille, near Liège in present-day Belgium, Pepin was the son of Charles Martel, the powerful Frankish ruler and military leader.

Incidentally, King Pepin was not actually short, despite his famous nickname. The epithet “the Short” is likely a misinterpretation of linguistic and historical nuances. The French term “Pippin le Bref” is more accurately translated as “Pepin the Brief” rather than “the Short”, possibly meaning ‘Young Peppin’, or the ‘Short-tempered’ or ‘Of few words’.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Pepin received a distinguished ecclesiastical education from Christian monks at the Abbey Church of St. Denis, near Paris. This religious upbringing profoundly influenced his character and future policies. In 741, following the death of his father, Charles Martel, Pepin and his elder brother Carloman inherited joint rule over the Frankish kingdom. Pepin became Mayor of the Palace in Neustria, Burgundy, and Provence, while Carloman ruled Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia.

The brothers faced immediate challenges to their authority. Their half-brother Grifo, son of Charles Martel’s second wife Swanahild, demanded a share of the inheritance. Pepin and Carloman swiftly dealt with this threat, besieging Grifo in Laon and ultimately imprisoning him in a monastery. Additionally, they had to suppress revolts in various regions, including Bavaria, Aquitaine, Saxony, and Alemannia.

To solidify their rule, Pepin and Carloman made a strategic decision in 743 to install Childeric III, the last Merovingian king, as a figurehead monarch. This move was intended to provide a sense of continuity and legitimacy to their governance.

Sole Rule and Path to Kingship

A significant turning point came in 747 when Carloman, after years of contemplation, decided to retire to a monastery in Montecassino, Italy. This decision left Pepin as the sole ruler of Francia, consolidating all power in his hands. As the de facto ruler, Pepin wielded supreme authority, while Childeric III remained king in name only.

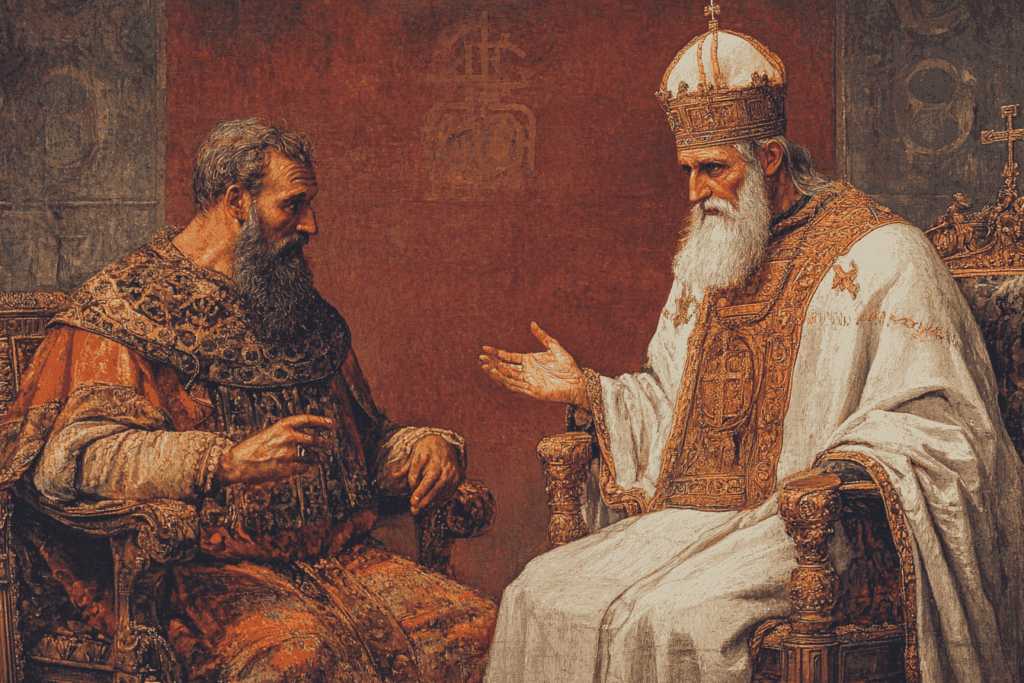

Recognizing the incongruity of this situation, Pepin took a bold step in 751. He sent envoys to Pope Zachary with a crucial question: “In regard to the kings of the Franks who no longer possess the royal power: is this state of things proper?” The Pope, who relied on Frankish military support against the Lombards, responded that the wielder of actual power should be called King.

Coronation and Legitimacy

Armed with papal approval, Pepin deposed Childeric III in 751, marking the end of the Merovingian dynasty. He was then elected King of the Franks by an assembly of Frankish nobles and anointed by Archbishop Boniface of Mainz in a coronation ceremony at Soissons. This event marked the beginning of the Carolingian dynasty and a new era in Frankish history.

Pepin’s legitimacy was further reinforced in 754 when Pope Stephen II traveled to Francia and anointed him for a second time at Ponthion. The Pope also bestowed upon Pepin and his sons the title of “Patricians of Rome,” further cementing the alliance between the Frankish monarchy and the papacy.

Military Campaigns and Territorial Expansion

As king, Pepin embarked on numerous military campaigns to expand and consolidate Frankish power. One of his most significant interventions was in Italy, where he came to the aid of the papacy against the Lombards.

Pepin’s Italian Campaigns

In 754, Pope Stephen II journeyed to Francia, seeking aid against the Lombard king Aistulf, who threatened Rome. Pepin the Short, newly anointed as King of the Franks, answered the call. He assembled a formidable army of 40,000 troops and marched towards Italy.

As the Frankish host approached, Aistulf rushed to block their passage at Susa in Piedmont. However, Pepin’s forces proved too strong. The Franks formed a phalanx, repelling the Lombard attack and nearly killing Aistulf in the process. Outmaneuvered, Aistulf retreated to his fortified capital at Pavia.

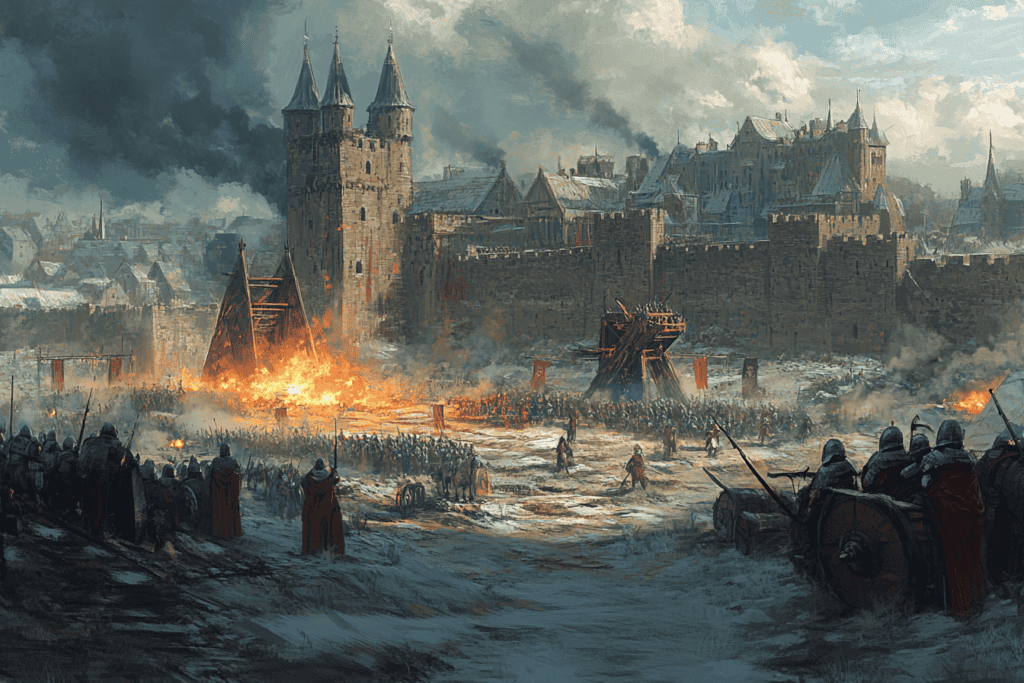

Pepin besieged Pavia, cutting off its supplies and communications. After a brief siege, Aistulf surrendered, agreeing to return the Byzantine territories he had seized. Pepin, instead of returning these lands to Byzantium, gifted them to the Church of Rome, laying the foundation for the Papal States.

However, Aistulf’s submission was short-lived. In January 756, he reneged on his pledge and attempted to storm Rome. Though Rome’s defenses held, Aistulf’s forces ravaged the surrounding papal lands in Campagna.

Hearing of this betrayal, Pepin swiftly organized a second expedition. The mere news of the approaching Frankish army was enough to compel Aistulf to lift the siege of Rome. As Pepin’s forces advanced, Aistulf retreated northward but failed to repel the Franks at the border.

Overwhelmed, Aistulf had no choice but to surrender unconditionally. This time, Pepin’s victory was decisive. He stripped Aistulf of all territories except Pavia, delivering the rest to the Pope. This act, known as the Donation of Pepin, solidified the temporal power of the papacy and reshaped the political landscape of medieval Italy.

Other Military Endeavors

Pepin also faced challenges within his realm. He had to put down revolts in Saxony and Bavaria, demonstrating his military prowess and determination to maintain Frankish supremacy.

One of his most prolonged struggles was against the rebellious duchy of Aquitaine, which resisted Frankish control. In 742, shortly after assuming power, Pepin and his brother Carloman responded swiftly to a revolt in Aquitaine by sending armies to ravage the region. This set the tone for Pepin’s approach to dealing with rebellious territories.

The Frankish king’s military operations were not limited to direct confrontations. He also employed siege tactics, as evidenced by his successful campaign to capture the Aquitanian capital of Bourges in 762. This siege showcased Pepin’s mastery of advanced military technology, including the use of trebuchets to breach the city’s walls.

Pepin’s campaigns against the Saxons laid the groundwork for his son Charlemagne’s more extensive Saxon Wars. While Pepin focused on maintaining Frankish overlordship and extracting tribute, Charlemagne would later escalate the conflict to include forced conversion to Christianity.

Throughout his reign, Pepin’s military actions against the Saxons were part of a larger pattern of expansion and consolidation of Frankish power. His successes in these campaigns helped establish the Carolingian dynasty as a dominant force in Western Europe.

Reforms and Governance

Pepin’s reign was characterized by significant reforms that strengthened the Frankish state.

He restructured the royal court, abolishing the position of mayor of the palace to prevent potential rivals. This role was replaced by a chamberlain who oversaw the treasury and monitored various sources of income. Furthermore, recognizing the financial disarray in the kingdom, Pepin initiated a monetary reform to stabilize the economy.

His proficiency in classical languages and grammar has led some historians to consider him as the initiator of the Carolingian Renaissance, which would reach its peak under his son Charlemagne.

Relationship with the Church

Pepin’s reign was marked by a close alliance with the Catholic Church, particularly the papacy. His cooperation with the papacy set a precedent for the future relationship between Frankish (and later, Holy Roman) emperors and the Church.

His support for the Church went beyond military assistance. Pepin actively supported the Christianization of the Germanic peoples within his realm. While he elevated the Church within Frankish society by granting numerous privileges to monasteries and churches. As a deeply religious ruler, Pepin called several church councils and promoted religious reform throughout his kingdom.

Personal Life and Character

Despite his moniker “the Short,” which alluded to his small stature, Pepin was renowned for his exceptional strength and courage. A famous anecdote recounts how he once beheaded a lion in a single stroke during a gladiatorial contest, demonstrating his physical prowess and bravery.

Pepin’s marriage to Bertrada of Laon, also known as Bertha Broadfoot, produced several children, including his successor, Charlemagne. The marriage was notable for its stability and longevity, unusual for royal marriages of the time.

Legacy

Pepin the Short’s reign from 751 to 768 marked a turning point in European history. He successfully transitioned the Frankish realm from the declining Merovingian dynasty to the vibrant and powerful Carolingian line. His military successes, administrative reforms, and alliance with the Church created a stable and expansive Frankish kingdom that his son Charlemagne would transform into an empire.

While Pepin’s achievements are sometimes eclipsed by the monumental legacy of Charlemagne, historians recognize his crucial role in setting the stage for the Carolingian era. His reign bridged the gap between the post-Roman world and the emerging medieval European order, influencing political, religious, and cultural developments for centuries to come.

Pepin the Short died on September 24, 768, at Saint-Denis, Neustria. He was succeeded by his sons Charlemagne and Carloman I, who initially ruled the kingdom jointly. However, Charlemagne would soon become sole ruler, building upon his father’s legacy to create the vast Carolingian Empire that would define European history for generations.