The world of Abbasid princesses and marriage politics was a dizzying maze of intrigue, ambition, and sometimes deadly rivalry. The glittering heart of the Abbasid Caliphate heard whispers of poison, saw the rise of brilliant queen-mothers, and the unending chess game between legitimate wives and ambitious concubines.

The Setting: Grandeur and Danger

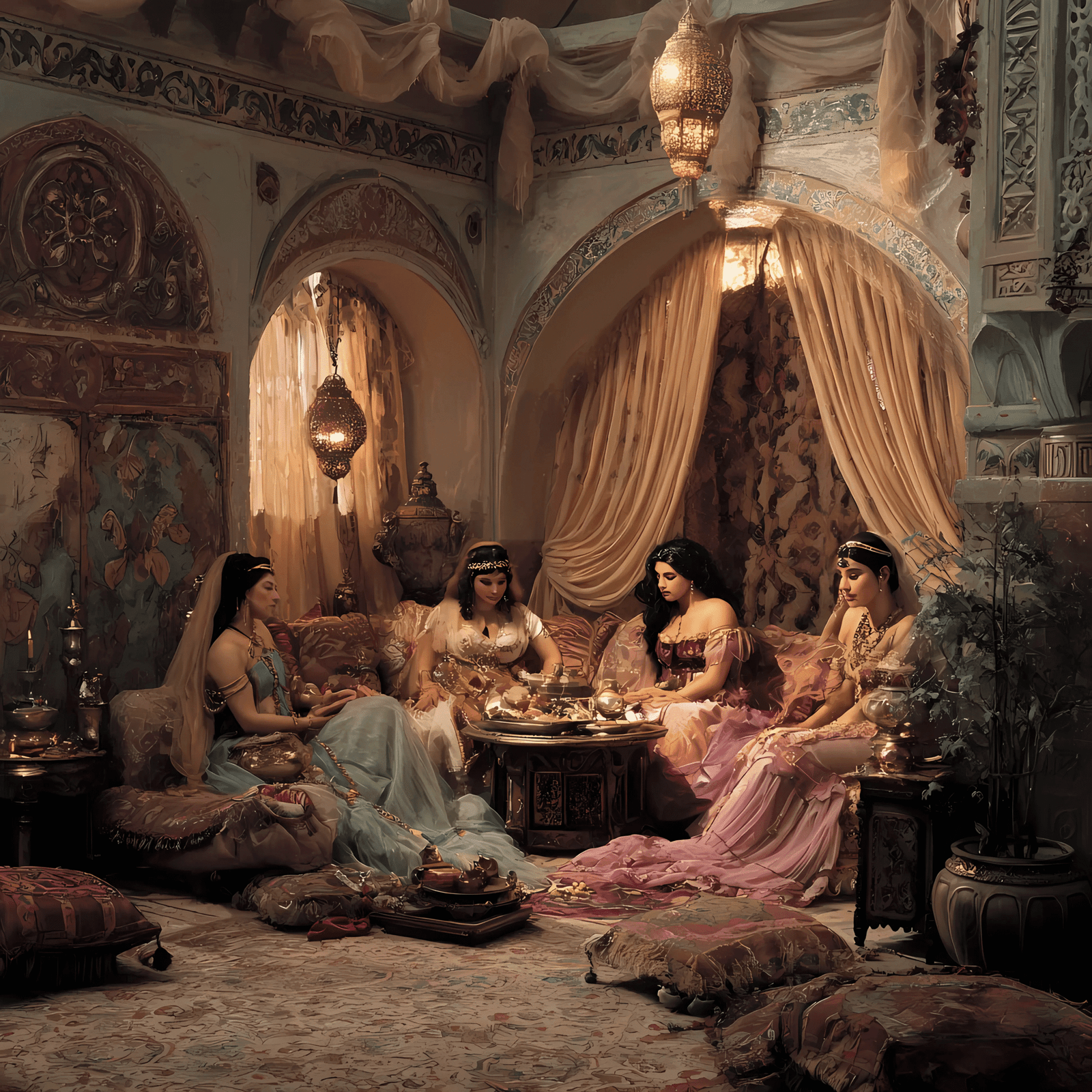

The Abbasid empire, at its peak in the 8th and early 9th centuries, was the envy of the world. Unimaginable wealth poured into its capitals, Baghdad and Samarra, from across Africa, Asia, and Europe. Palaces sprawled across the banks of the Tigris, adorned with gardens, mosaics, and shimmering pools. But beneath that opulent surface, the caliphs’ families – especially their wives and daughters – lived in a world governed by ambition, rivalry, and relentless maneuvering for influence.

While tax and tribute flowed, so did the tangled lines of succession and the need for political marriages. The Abbasid harem was not simply a place of leisure and luxury; it was the engine room of empire, a crucible where the fate of the caliphate was forged – sometimes with deadly consequences.

The Harem: Institution of Power and Isolation

Unlike the popular image of harems as mere pleasure quarters, the Abbasid harem was a formidable, hierarchical institution. At its head was not the caliph’s wife, but his mother: the Queen Mother wielded vast influence over palace politics. Below her were a multitude of wives, concubines, slave women, and princesses. Some, like Arwa and Khayzuran, became public figures in their own right, running courts, receiving ambassadors, and dispensing patronage.

The primary wives – often aristocratic Arab women – enjoyed honored status but found themselves in perpetual rivalry with ambitious concubines, many of whom started their lives as slaves captured in war or bought in distant markets. To give birth to a son for the caliph was to elevate oneself into the rare class of umm al-walad, a mother of royal progeny, who could never be sold again, and whose son might one day rule the greatest empire on earth.

Below the wives and umm al-walad, concubines – acquired through war or purchase – inspired both fascination and fear. With enough wit, beauty, and luck, a concubine could rise to dizzying heights and become the power behind the throne.

Marriage as Power Politics

For the Abbasids, marriage was not just a personal affair, but a diplomatic tool of first importance. Marriages bound caliphs to powerful Arab clans or distant rulers, cementing alliances or integrating new regions into the imperial house. But this delicate balancing act came at a price: an unceasing jockeying for priority and influence among wives, concubines, and their children.

The caliphs’ daughters were equally valuable assets, bartered in the grand game of geopolitics, their marriages the subject of intense negotiation and, sometimes, deadly consequence.

The Rise of Queen-Mother Khayzuran

One of the most remarkable figures in Abbasid harem politics was Khayzuran, a former slave turned queen-mother. Originally from South Arabia and purchased by Caliph al-Mahdi, she quickly became not only his favored consort but a legal wife – one of four. Intelligent and commanding, Khayzuran established her own court, received ambassadors, decided legal cases, and minted coins in her own name, a feat with no precedent in Arab tradition.

She bore two sons – al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid – each destined for greatness. As queen-mother, Khayzuran expected to rule behind the scenes, but her son al-Hadi resented her public influence and sought to curtail her power. Their rivalry became legendary in the chronicles of the court.

Poison in the Palace: Legends and Realities

It was in this fraught atmosphere that tales – sometimes rooted in fact, sometimes in the fevered imagination of chroniclers – began to swirl of courtly poisonings and mysterious deaths. The most dramatic involved rival wives and concubines, each vying for their children to inherit the throne.

Poison was the weapon for those unwilling to risk open war. The tight seclusion and intense surveillance of the harem made assassination risky, yet also offered opportunities for discreet conquest. At banquets and in private chambers, food and wine might hide fatal secrets. The sudden illness of a rival’s child or the unexpected death of a concubine became the talking point of whispering courtiers and ambitious eunuchs.

During al-Hadi’s reign, palace intrigue reached a fever-pitch. Khayzuran, long accustomed to authority, found her powers challenged by al-Hadi, who openly rebuked her for receiving male visitors. Tradition holds that she was involved in his sudden death, and the possibility that poison played a role lingers in every retelling: was it ambition, revenge, or mere accident that transformed family disputes into deadly tragedy?

The Tragic Fates of Abbasid Princesses

Within this world, Abbasid princesses navigated perilous waters. Arranged marriages – sometimes to cousins, sometimes to distant rulers or ambitious generals – were fraught with risk. For queens and concubines alike, the birth of a son was a triumph, yet it could also mark them for destruction if they threatened the status of others.

Harun al-Rashid’s court offers an especially vivid tableau of harem rivalry. His principal wife, Zubaydah – herself the daughter of Khayzuran’s sister – enjoyed every privilege, including her own household and palace. Her son, al-Amin, was named heir over his elder half-brother, al-Ma’mun, whose mother was a concubine from Sogdia. The rivalry between these branches of the family set the stage for bitter succession struggles and, eventually, civil war.

Rumors swirled that some princesses, poisoned or eliminated, fell victim to their rivals. Chroniclers relay tales of women forced into marriage as political pawns, then discarded or killed when they became inconvenient. Eunuchs and trusted servants, privy to a thousand secrets, stood both as protectors and dangers – equally likely to administer medicine or poison.

Ambition and Agency: Queens Who Fought Back

Despite the dangers, many Abbasid women were anything but passive victims. Some, like Khayzuran, bent the court to their will; others, like Zubaydah, left lasting public legacies through works of charity and piety, such as her refurbishment of the water supply to Mecca’s holy sites.

These women understood the stakes of harem politics. They built networks of supporters inside and outside the palace, allying with eunuchs, courtiers, and even foreign ambassadors. Through shrewd alliances, strategic gifts, and, at times, calculated violence, they forged their own spheres of influence – narratives that persist in both history and legend.

The Power of Seclusion

Paradoxically, the intense seclusion of the harem did not prevent its women from shaping statecraft. The Queen Mother and favored wives mediated disputes, arbitrated legal cases, and dispensed charity. Their influence was felt in the appointment of courtiers, the bestowal of offices, and the resolution of succession crises. Even in seclusion, their words could topple viziers or raise generals to the peak of power.

Rivalry Without Mercy

When the stakes were survival for themselves and their children, Abbasid princesses could be both fierce and ruthless. Chroniclers record acts of calculated treachery: secret pacts with eunuchs and physicians, the forging of incriminating evidence, and, yes, instances of poisonings both attempted and alleged.

In the struggle for survival, the line between victim and perpetrator was thin. A princess once favored could swiftly become expendable if political winds shifted – or if her son failed to win the caliphate after all.

Decline and Transformation

As the centuries passed and the caliphate fragmented, the structure of the harem changed. Public roles for wives and mothers diminished. By the 9th and 10th centuries, the system shifted toward the sultans grooming heirs among their sons with concubines, and the era of the independent queen with her own palace and court faded into history.

But the legends survived: tales of poisoned princesses, rivalry, and power behind the curtain continued to haunt the memory of the Abbasid golden age, a testament to the indelible impact of these women on the empire that once dazzled the world.