The medieval history of Denmark is marked by a series of formidable monarchs. Among these, Sweyn II Estridsson stands out as a king whose nearly three-decade rule laid the foundations for a united Denmark. His life was one of warfare, dynastic struggle, and religious transformation – elements that together narrate the saga of a king who deftly navigated the turbulent waters of Viking era politics.

Early Life: Royal Blood and Noble Roots

Sweyn II Estridsson was born around 1019 in England, a product of two influential Danish lines. His father, Ulf Thorgilsson, was a Danish nobleman and powerful jarl who held significant sway in Denmark as a chieftain and regent under the reign of the great King Cnut the Great.

Sweyn’s mother, Estrid Svendsdatter, was no less distinguished as she was the daughter of King Sweyn Forkbeard and sister to both King Harald II and King Canute the Great. Thus, from birth, Sweyn was intimately connected to the royal bloodlines that intertwined Danish, English, and Norwegian regal heritage. This royal pedigree not only provided him with a claim to power but also placed him in the midst of familial and political rivalries that would shape his future.

The murder of his father in 1027 forced the young Sweyn into exile in Sweden, a refuge that preserved his life and allowed him to mature away from the hostile intrigues of Danish court politics. Yet, his exile was only a temporary setback; Sweyn’s lineage and his own talents destined him for the throne.

Struggle and War: The Road to the Danish Throne

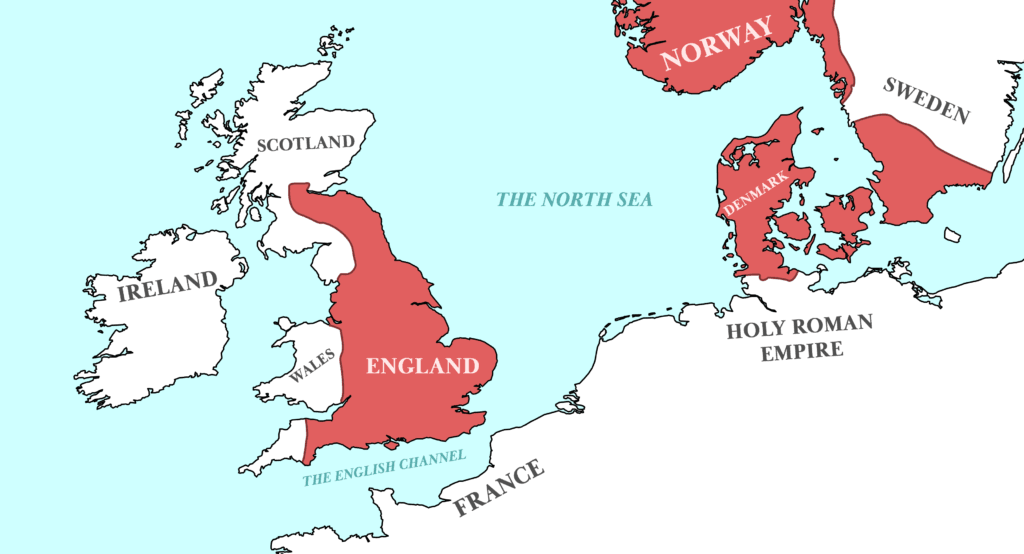

Sweyn’s path to kingship was far from straightforward. After the death of King Canute the Great in 1035, Scandinavia was thrown into disarray. The North Sea Empire, spanning England, Denmark, and Norway under Canute, fragmented as local rulers contested for power. In Denmark, the situation was chaotic, with Magnus I of Norway initially asserting dominance over the Danish crown.

Sweyn was appointed jarl of Jutland by King Magnus I, yet ambitions remained. In 1042, the political balance shifted sharply. The Danish King Harthacnut, who ruled both Denmark and England, died suddenly without an heir, leaving a power vacuum in the south. Magnus, through prior treaties and opportunistic claims, wanted to secure Denmark for himself. His main opponent was Sweyn II Estridsson. Sweyn was acclaimed king by Danish nobles in Viborg, signaling Denmark’s resistance to Norwegian overlordship. His claim sparked a brutal and protracted conflict with Magnus and later Magnus’s successor Harald Hardrada.

Magnus struck quickly, invading Denmark with military force and decisively defeating Sweyn in several engagements. Sweyn fled to Sweden, where he found refuge and support under King Anund Jacob.

Magnus was able to proclaim himself king over both Norway and Denmark – a position of immense prestige that recalled the North Sea empire of Cnut. Yet Sweyn was not simply defeated; he lingered as a persistent rival.

Sweyn rallied support and with Anund Jacob launched joint military operations against Magnus. Their campaigns included skirmishes and raids into Zealand and Skåne, while Magnus responded with swift counterattacks. This back-and-forth gave way to a prolonged cycle of punitive campaigns. Sweyn was sometimes forced to retreat to Sweden and other times held firm in parts of Denmark like Scania. Anund Jacob’s support was crucial for Sweyn’s survival: by providing military backing and a safe haven, the Swedish King helped Sweyn maintain pressure on Magnus.

By the mid-1040s, the war was rhythmically fierce but inconclusive. Magnus’s dominance in Denmark rested on the martial loyalty of his Norwegian forces, but Sweyn’s resourcefulness meant he could never fully be eliminated. Then, in 1047, the pattern of struggle broke abruptly – Magnus died unexpectedly, perhaps from an illness, leaving no direct heirs.

Harald Hardrada Enters the Stage

Magnus’s death was a turning point. By agreement between rivals, the Norwegian crown passed to Harald Sigurdsson – better known to history as Harald Hardrada – while the Danish throne reverted to Sweyn II Estridsson. But the pact that divided the realms did not end the fighting. For Harald, a veteran of the Varangian Guard and a man forged in the wars of Byzantium, losing Denmark was intolerable. He saw himself as the rightful ruler of both realms, with Magnus’s reign as precedent.

Harald wasted no time. Within months of taking the Norwegian throne, he began intensifying Norway’s naval power, aiming to challenge Sweyn directly. From 1047 onward, Harald launched annual summer campaigns into Denmark. The strategy was brutal and methodical: fleets would sail from Norway to raid the Danish coasts, seize goods, burn settlements, and terrorize the population into submission.

These invasions reflected Harald’s personal style of kingship – relentless, uncompromising, and theatrical. He did not always press for decisive battles; instead, he waged war as a sustained demonstration of force, a reminder to Sweyn that Denmark’s safety remained hostage to Norwegian ambitions.

The Endless Raids and Escalations

The war between Harald and Sweyn unfolded not in single grand clashes, but in years-long sequences of skirmishes, coastal assaults, and naval maneuvering. Danish areas such as Jutland, Zealand, and Funen saw repeated incursions. Villages were burned, churches plundered, and local leaders were forced into uneasy accommodation with the Norwegians.

Sweyn, however, had his own methods. He built alliances with the Swedish King Emund and cultivated support among the Danish aristocracy, who favored his rule to the harsh taxes and requisitions that Harald’s conquest would bring. Sweyn avoided full-scale battle where possible, preferring to harry Norwegian forces, retaliating with his own raids into southern Norway or against Norwegian merchant shipping.

Occasionally, the war did produce large confrontations. In 1050, Harald led a massive fleet to attack Aarhus, seeking to draw Sweyn into a decisive fight. Sweyn refused, withdrawing inland and avoiding engagement, which left Harald furious. Such evasions were typical of Sweyn’s policy: he understood that Harald’s warriors were unmatched in direct combat, but Norway’s wider ambitions could be starved by denying them conclusive victories.

The Pitched Battle of Niså

The closest the war came to a decisive resolution was the Battle of Niså, fought in 1062. By this point, neither side had achieved supremacy, and both rulers had spent over a decade locked in seasonal wars. Harald sought to break the cycle through an overwhelming naval assault, bringing an enormous fleet across the Skagerrak toward the mouth of the river Niså. Sweyn responded with an equally large force.

The battle began as a classic Norse sea-fight: ships locked together, warriors leaping across decks, arrows and spears flying, axes crunching through shields. Harald’s disciplined skills, honed from years of warfare abroad, gave the Norwegians the upper hand. Sweyn’s fleet broke under the assault, and he was forced to flee the battlefield by night, leaving Denmark momentarily exposed.

Yet even this victory proved hollow for Harald. Despite his triumph, Sweyn retained his throne, and the Danish nobility did not abandon him. Norway’s logistics could not maintain permanent occupation, and Harald withdrew. The war resumed its old rhythms – raids, retaliations, and political maneuvering.

Stalemate and the End of the War

By the early 1060s, exhaustion gripped both kingdoms. The annual destruction wore on commerce, agriculture, and the population. While Harald had the pride of victory at Niså, he had nothing tangible to show for it in terms of territory. Sweyn, for his part, understood that while he could preserve his throne, continued war brought instability to his realm.

In 1064, diplomacy finally succeeded where years of combat had failed. Harald and Sweyn reached a formal peace agreement: Norway renounced its claim to the Danish crown, and both rulers recognized each other’s sovereignty. For Harald, it was a bitter compromise, but it freed his hand for other ambitions – in particular, his later attempt to claim the English throne in 1066, which would end in disaster at Stamford Bridge.

For Sweyn, the war cemented his position as king and allowed him to focus on internal strengthening of Denmark, continuing a reign that would last into the late 1070s. Neither man forgot the long struggle, but both gained from ending it before mutual attrition destroyed them.

Reign: Consolidation, Church, and Statecraft

Sweyn Estridsson’s reign from 1047 to 1076 was pivotal in shaping medieval Denmark’s political structure and territorial integrity. Though he was courageous in battle, Sweyn’s greatest legacy lies in his ability to consolidate royal power through diplomacy, ecclesiastical reforms, and strategic governance rather than mere military conquest.

One of his major achievements was reclaiming and securing the regions of Jutland and Scania, which were critical both economically and militarily. These territories had been contested during the wars with Norway and Sweden, and their reintegration into the Danish kingdom helped stabilize Sweyn’s authority.

Sweyn also understood the importance of the church in legitimizing royal authority and unifying the kingdom. He worked closely with the Church and the Papacy to reorganize Denmark’s ecclesiastical structure. He established dioceses and laid the groundwork for the creation of the Archbishopric of Lund, a move that brought Denmark’s church hierarchy in line with Roman Catholic norms and significantly increased the king’s influence over religious matters.

An intelligent and literate ruler, Sweyn is known to have corresponded with the Pope and other religious leaders. His reign marked the formalization of Christianity’s hold in Denmark, transforming it into a Christian kingdom with strong ties to the wider European Christendom.

Legacy: Father of Kings and Founder of a Dynasty

Sweyn Estridsson’s personal life was as prolific as his political career. He was married at least twice and fathered at least 20 children outside marriage, but five of his sons notably ascended to Denmark’s throne, ensuring the continuation of the Estridsson dynasty’s influence over Danish history. Sweyn’s these were Harald III Hen, Canute IV (later canonized as Saint Canute), Olaf I Hunger, Eric I Evergood, and Niels.

Through his descendants, Sweyn’s bloodline extended beyond Denmark’s borders into the royal houses of Scotland and England, influencing European history in the centuries that followed. His lineage is connected to Queen Margaret of Denmark and through her marriage to James III of Scotland, which interwove Danish royal blood with British royalty.

Sweyn’s long reign provided Denmark with stability after decades of conflict and fragmentation. His cooperation with the church, strengthening of royal authority, and diplomatic maneuvering helped transition Denmark from a loosely organized Viking kingdom to a centralized medieval monarchy.

Sweyn II Estridsson in Historical Perspective

When viewed against the backdrop of 11th-century Scandinavia, Sweyn Estridsson emerges as more than just a warrior king. His reign bridged the old Viking age and the emerging medieval European order. His life was framed by battle and politics, yet his vision extended beyond the battlefield to governance, religion, and legacy building.

While his military campaigns sometimes faltered and he faced formidable opponents like Harald Hardrada, his endurance and political acumen ultimately secured Danish independence and set the stage for future expansion. His reign is considered a cornerstone in the foundation of modern Denmark.