In the depths of winter, when darkness envelops the land and cold winds howl across the Irish countryside, the ancient Celts celebrated one of their most important festivals: the winter solstice. Known as “Grianstad an Gheimhridh” in Irish Gaelic, this astronomical event marked the shortest day and longest night of the year, typically falling around December 21st. For the Celtic Irish, this was a time of profound significance, blending spiritual beliefs, astronomical knowledge, and communal traditions into a rich tapestry of midwinter celebrations.

The Ancient Roots of Midwinter Observance

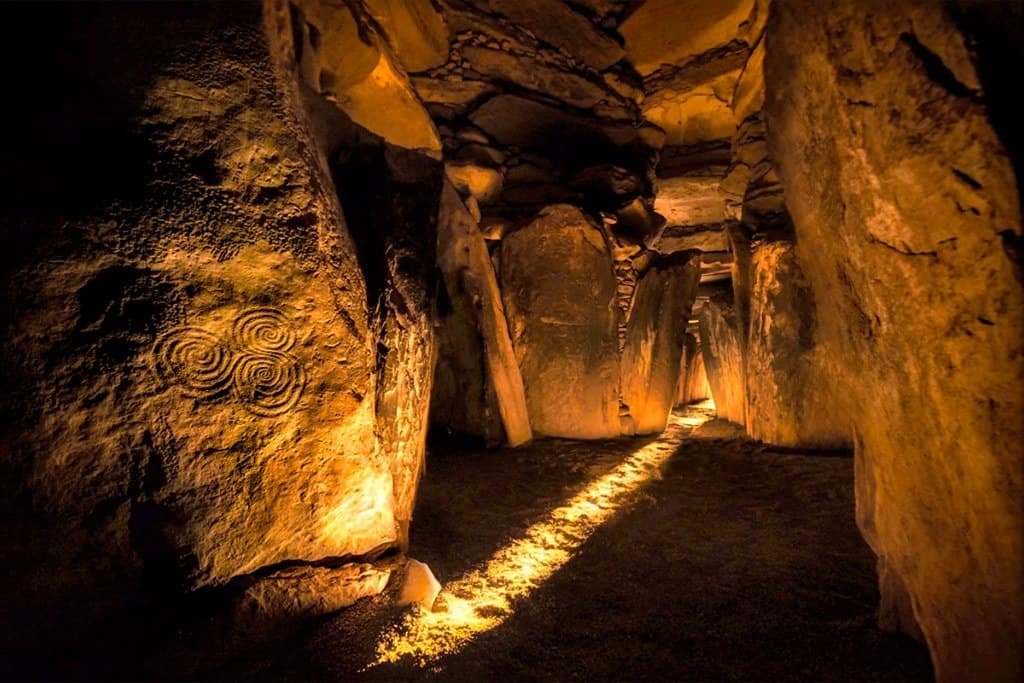

The celebration of midwinter in Ireland predates even the Celtic culture, stretching back over 5,000 years. The most striking evidence of this ancient observance is the spectacular Newgrange monument in County Meath. Built around 3200 BC, this Neolithic passage tomb demonstrates the extraordinary astronomical knowledge of Ireland’s prehistoric inhabitants. Its entrance is precisely aligned with the rising sun on the winter solstice, allowing a narrow beam of light to illuminate the inner chamber for just 17 minutes at dawn.

This alignment speaks to the deep connection our ancestors felt with the cycles of nature and the celestial bodies above. For them, the winter solstice was not merely an astronomical event but a pivotal moment in the year’s cycle, symbolizing the rebirth of the sun and the promise of renewed life.

Celtic Mythology and the Battle of Light and Dark

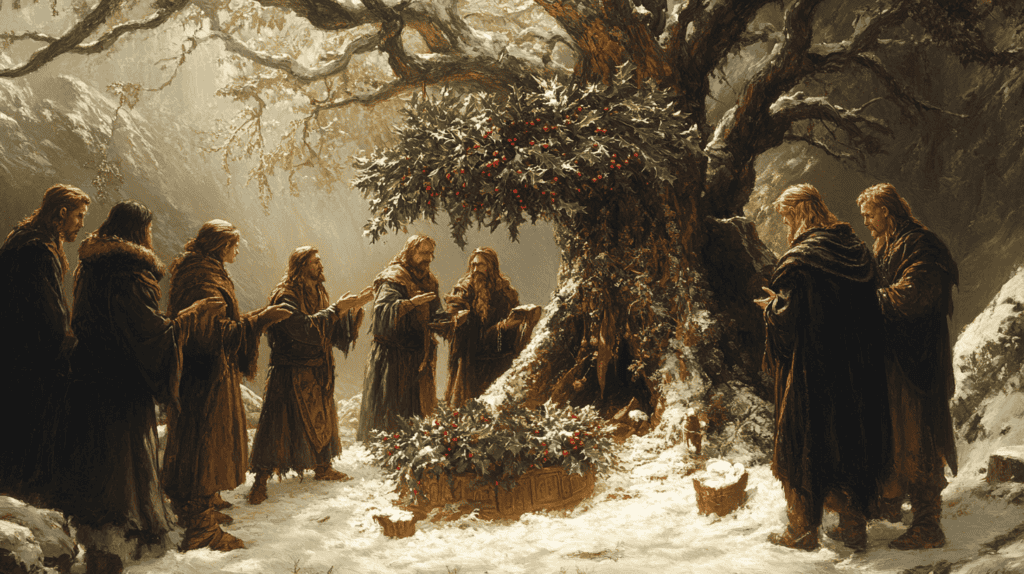

As Celtic culture took root in Ireland, the midwinter celebration became imbued with rich mythological significance. In Celtic lore, the solstice marked an epic annual battle between two mighty forces: the Oak King, representing light and summer, and the Holly King, embodying darkness and winter.

This cosmic struggle played out each year at the winter and summer solstices. At midwinter, the Oak King would emerge victorious, signaling the gradual return of longer days and the sun’s warmth. This mythological narrative provided a framework for understanding the cyclical nature of the seasons and offered hope during the darkest time of the year.

Newgrange: A Monument to Midwinter Magic

The legacy of Newgrange continued long after its Neolithic builders, becoming an integral part of Celtic mythology. Known as “An Brug” in Celtic lore, Newgrange was believed to be the dwelling place of the Tuatha De Danann, a mythical race inhabiting the Otherworld.

The winter solstice alignment at Newgrange took on new significance for the Celts. The illumination of the inner chamber by the solstice sun was seen as a moment when the boundaries between our world and the Otherworld grew thin. It was a time of magic and possibility, when the wisdom of the ancestors and the power of the gods could be accessed.

Today, this ancient tradition continues to captivate. Each year, thousands enter a lottery for the chance to witness the solstice illumination inside Newgrange. Only 20 lucky individuals are chosen to stand within the chamber as the golden light of the rising sun penetrates the darkness, creating a truly awe-inspiring spectacle.

Rituals and Traditions of Celtic Midwinter

The Celtic Irish marked the midwinter season with a variety of rituals and customs, many of which have echoes in modern Christmas traditions:

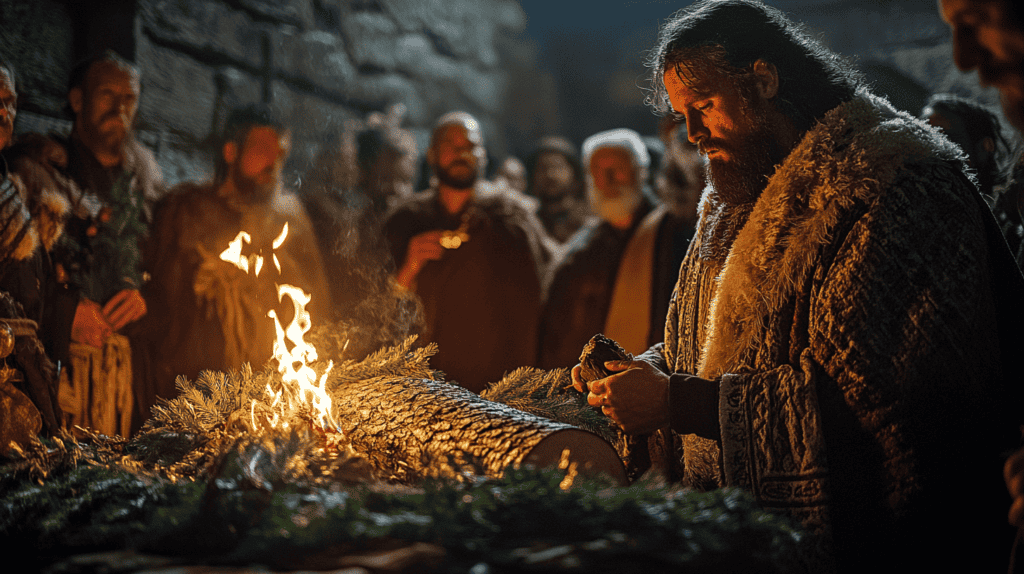

The Yule Log

One of the most important midwinter rituals was the burning of the Yule log. This tradition, shared by both Norse and Celtic cultures, involved selecting a large log, often from a sacred oak tree. The log was carefully chosen and adorned with evergreen boughs before being ceremonially lit in the hearth.

The Yule log served multiple purposes. It was a symbolic representation of the returning sun, its flames bringing light and warmth to the darkest time of the year. The log was also believed to have protective qualities, warding off evil spirits during this liminal period. Traditionally, a piece of the previous year’s log was used to light the new one, creating a continuity of sacred flame from year to year.

Evergreen Decorations

The use of evergreen plants played a crucial role in Celtic midwinter celebrations. Holly, ivy, and mistletoe were gathered and used to decorate homes and sacred spaces. Each plant held its own symbolic significance:

- Holly, with its prickly leaves and red berries, was seen as a powerful protective charm. It was hung over doors and windows to ward off evil spirits. The red berries were also associated with fertility and the life-force that persisted even in the depths of winter.

- Mistletoe, revered by the Druids, was believed to have powerful healing and fertility properties. Its white berries were seen as symbols of purity and the divine masculine.

- Evergreen boughs, which retained their green color throughout winter, symbolized the endurance of life and the promise of spring’s return.

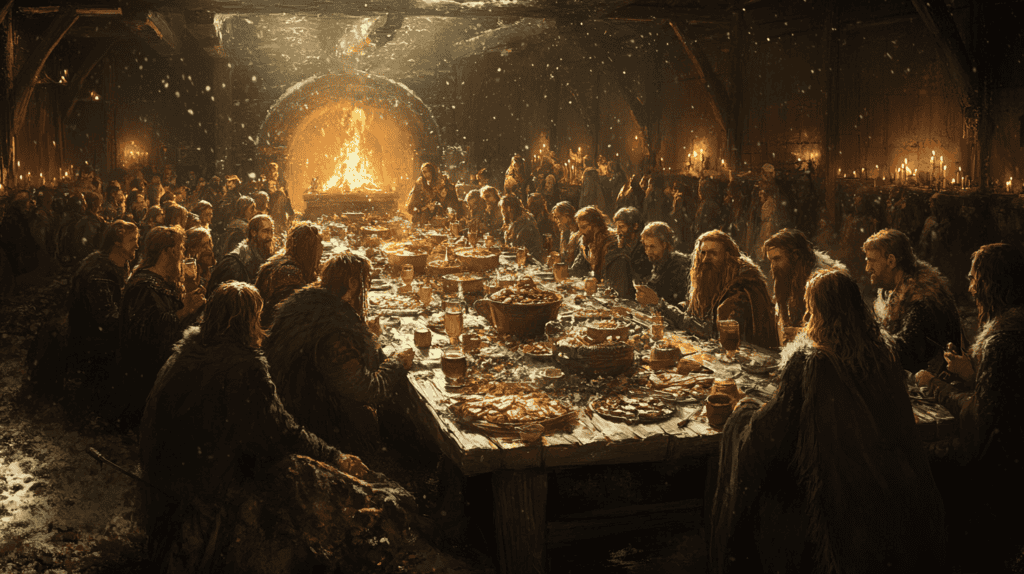

Feasting and Community

Midwinter was a time for coming together, sharing food, and strengthening community bonds. As the agricultural work of the year came to a close, people gathered to feast on the fruits of the harvest and the spoils of the hunt. These communal meals were not just about sustenance but also about reinforcing social ties and expressing gratitude for surviving another year.

The feast would likely have included whatever local produce was available – perhaps preserved meats, root vegetables, and grains. Mead or ale, both sacred drinks in Celtic culture, would have flowed freely, adding to the festive atmosphere.

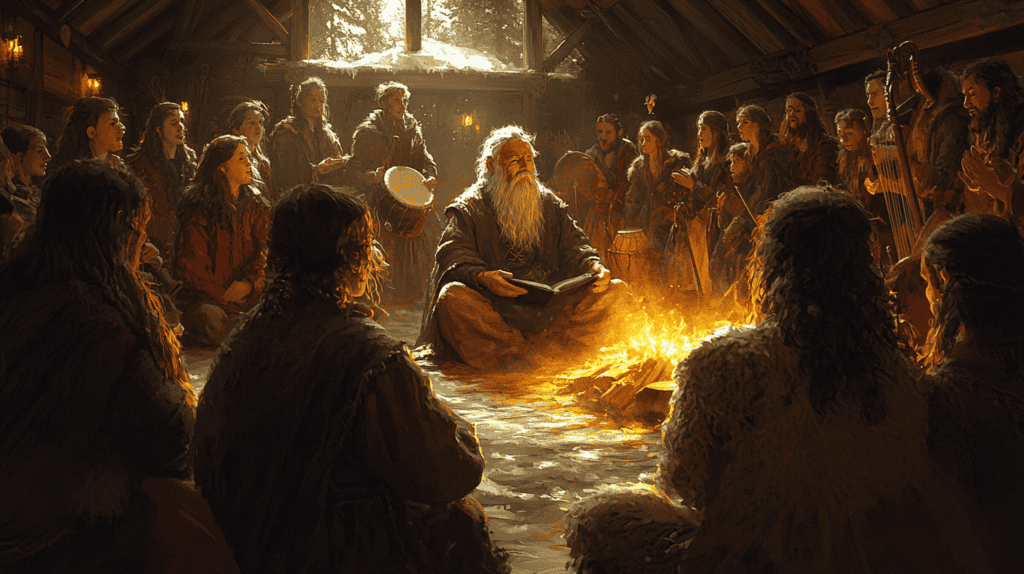

Storytelling and Music

With the long nights of winter providing ample time for indoor activities, storytelling and music played a crucial role in Celtic midwinter celebrations. Bards and storytellers would recount tales of heroic deeds, mythological battles, and the cycles of the seasons. These stories served not only as entertainment but also as a means of passing down cultural knowledge and reinforcing communal values.

Music, too, was an integral part of the festivities. Harps, pipes, and drums would accompany songs and dances, filling the air with joyous sounds to counter the winter’s silence.

The Influence of Celtic Midwinter on Modern Traditions

Many of the Celtic midwinter traditions have been absorbed into modern Christmas celebrations. The use of evergreen decorations, the centrality of light (now in the form of Christmas lights and candles), and the emphasis on feasting and community gatherings all have roots in these ancient practices.

Whether we stand in awe as the solstice sun illuminates the land or simply pause to notice the gradual lengthening of days, we connect with a lineage of ancestors who found hope and meaning in the turning of the year. In doing so, we keep alive the spirit of Celtic midwinter – a celebration of light’s triumph over darkness, of life’s persistence in the face of winter’s chill, and of the eternal cycle of renewal that governs both nature and our own lives.