Battle of Tours (732)

The Battle of Tours, also known as the Battle of Poitiers, took place on October 10, 732, between the Frankish forces led by Charles Martel and the Umayyad Caliphate’s army led by Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi. This battle is considered a pivotal moment in European history, as it halted the northward expansion of Islam into Western Europe.

Background

The Umayyad Caliphate had rapidly expanded across the Iberian Peninsula after their victory over the Visigothic Kingdom in 711. By 719, they had crossed the Pyrenees into what is now France, capturing Narbonne and establishing a foothold in the region. Their incursions continued into Aquitaine and Burgundy, with significant raids reaching as far as Bordeaux and Autun.

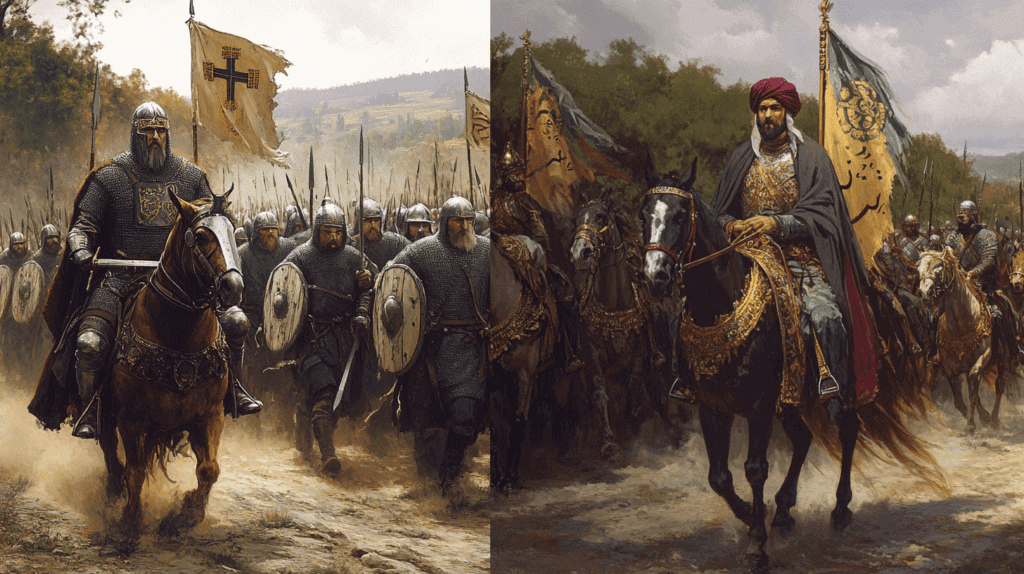

Prelude to the Battle

In 732, Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi led a large Umayyad force northward, aiming to expand their territory and plunder the rich lands of the Franks. Charles Martel, the mayor of the palace of the Frankish kingdom of Austrasia, mobilized his forces to confront the invaders. The Frankish army, composed mainly of infantry, was significantly outnumbered by the Umayyad cavalry.

The Battle

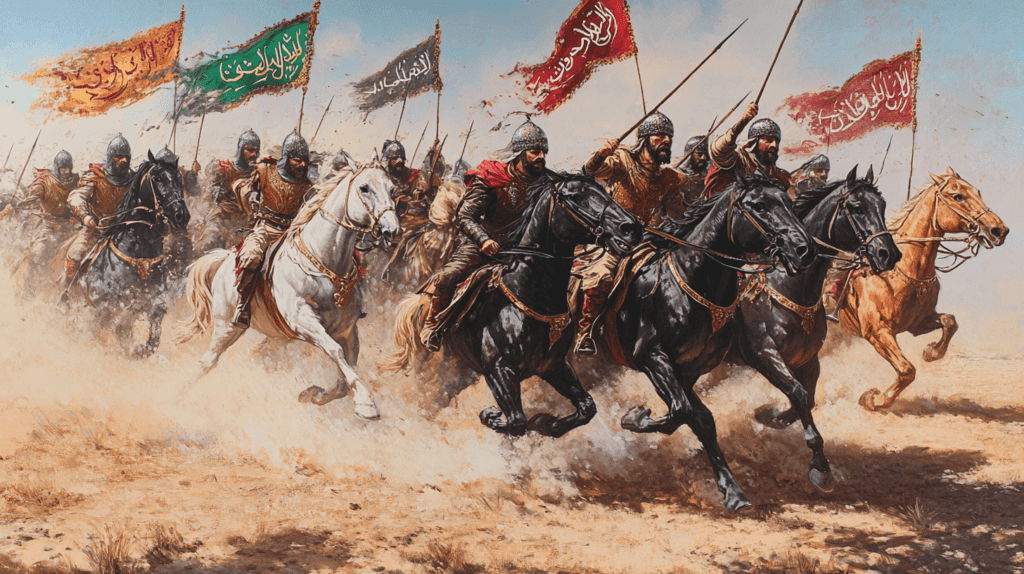

The invading forces were taken by surprise when they encountered a substantial army blocking their route to Tours. Charles had successfully achieved the element of surprise he desired, aided by the Muslim army failing to scout the lands ahead of them. Instead of launching an attack, Charles opted to establish a defensive, phalanx-like formation based on his experienced infantry. According to Arab sources, the Franks formed a large square, using the hills and trees in front of them to disrupt or break up the Muslim cavalry charges.

For a week, the two armies engaged in minor skirmishes while the Umayyads awaited the arrival of their full strength. Despite being an experienced commander, ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân was outmanoeuvred, allowing Charles to concentrate his forces and choose the battlefield. Additionally, the Umayyads were unable to gauge the size of Charles’ army, as he had used the forest to conceal his true numbers. Charles’ infantry, seasoned and battle-hardened, was his best hope for victory, with many having fought under him for years, some since as far back as 717. Alongside his army, he had levies of militia who had primarily been used for gathering food and harassing the Muslim army.

While many historians have believed that the Franks were outnumbered at the onset of battle by at least two to one, some sources, such as the Mozarabic Chronicle of 754, dispute this claim. Charles Martel correctly anticipated that ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân would feel compelled to engage in battle and attempt to loot Tours. Neither side was eager to attack, however, Abd-al-Raḥmân was isolated in a foreign land with a difficult supply chain and winter was approaching, which forced him to confront the Frankish army positioned on the hill. Charles’ decision to remain in the hills proved crucial, as it forced the Umayyad cavalry to charge uphill and through trees, reducing their effectiveness. Charles had been preparing for this confrontation since the Battle of Toulouse a decade earlier. The disciplined Frankish soldiers withstood the repeated assaults without breaking, even though the Arab cavalry broke into the Frankish square several times.

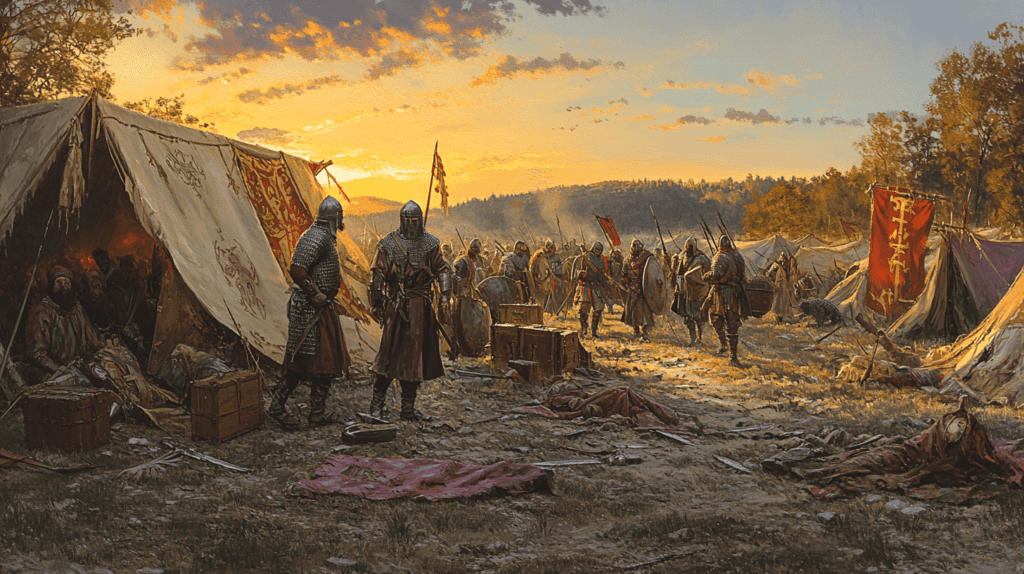

As the battle progressed, Duke Odo initiated a pivotal flanking manoeuvre that shifted the balance in favor of the Franks. He sent his cavalry on a wide flank, reaching the distant Muslim encampment, where the Umayyad tents and their abundant plunder from the recent sacking of Bordeaux were located.

Odo inflicted substantial losses, reclaimed the valuable treasure, freed some 200 captive Franks, and most importantly, caught the enemy’s attention. What followed exceeded his expectations. Upon realizing their camp and plunder were under attack, many Umayyad units from the central battlefield frantically rushed back to protect their loot. This unexpected situation caught al Ghafiqi off guard. His attempts to rally his troops were futile, and Charles Martel, fully aware of the unfolding chaos, seized the moment.

As the Umayyad forces scattered to retrieve their loot, Martel directed his forces from all sides, engaging in both pursuit and encirclement. The remaining Umayyad troops were surrounded and suffered heavy casualties. Among the fallen was al Ghafiqi himself, who died while trying to rally his men. Meanwhile, Duke Odo swung north again, cutting off the fleeing Umayyads and inflicting further losses.

Aftermath and Significance

The victory at Tours solidified Charles Martel’s reputation as a formidable military leader and laid the groundwork for the Carolingian Empire. The battle is often credited with preserving Christianity in Western Europe and preventing the further spread of Islam beyond the Iberian Peninsula.

While the immediate impact of the battle may have been overstated in later historical narratives, its long-term significance in shaping the political and religious landscape of Europe is undeniable. The establishment of Frankish power in Western Europe set the stage for the rise of the Carolingian dynasty and the eventual formation of the Holy Roman Empire.