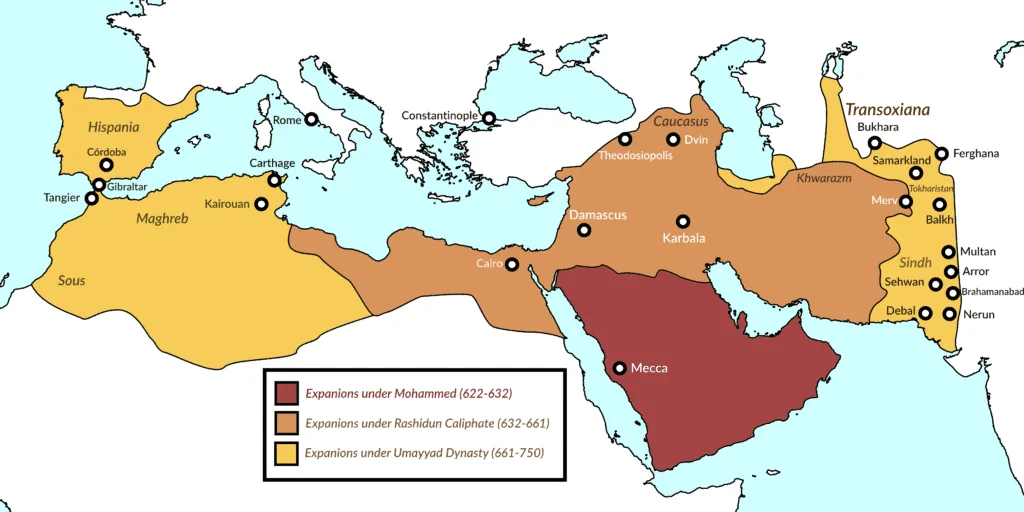

The rise of the Umayyad Empire and its expansion across North Africa into Spain and eastwards into India to create one of the biggest empires ever seen is a major chapter in world history, marked by rapid conquests, political intrigue, and cultural transformation.

Pre-Islamic Origins

The story of the Umayyads begins in pre-Islamic Mecca, where they were a prominent clan of the Quraysh tribe. The Quraysh held a position of prestige among Arab tribes due to their role as protectors of the Kaʿba, a sacred sanctuary in Mecca. The Umayyads, or Banu Umayya, traced their lineage to Umayya ibn Abd Shams, a descendant of Abd Manaf ibn Qusayy, who lived in the late 5th century.

Umayya succeeded his father as the qa’id (wartime commander) of the Meccans, a position that involved overseeing military affairs during times of conflict. This early experience in leadership would prove invaluable for future generations of Umayyads. By the year 600, the Quraysh, including the Umayyads, had developed extensive trade networks across Arabia, forming alliances with nomadic tribes to secure their routes.

The Coming of Islam

When the Prophet Muhammad began preaching Islam in Mecca in the early 7th century, the Umayyads initially opposed him. However, they eventually embraced the new faith before Muhammad’s death in 632. This conversion would prove crucial for their future role in the Islamic world.

The Rashidun Caliphate and the First Fitna

Following Muhammad’s death, the Muslim community was led by the four Rashidun (rightly-guided) caliphs. The third of these, Uthman ibn Affan, was a member of the Umayyad clan. His reign from 644 to 656 saw the appointment of several Umayyads to important governorships, including Mu’awiya I as governor of Syria.

Uthman’s assassination in 656 sparked the First Fitna, or civil war, which pitted Ali, the fourth caliph, against Mu’awiya. This conflict lasted from 656 to 661 and ended with Ali’s death and Mu’awiya’s ascension as the first Umayyad caliph.

The Establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate

In 661, Mu’awiya I founded the Umayyad Caliphate, establishing Damascus as its capital, moving it from Mecca. This marked a significant shift in Islamic history, as the Umayyads became the first hereditary dynasty to rule the Muslim world. Mu’awiya’s reign laid the foundation for a centralized administration and a powerful military, which would be crucial for the empire’s future expansions.

Expansion and Consolidation

Under Mu’awiya and his successors, the Umayyad Caliphate embarked on a period of rapid expansion. They incorporated vast territories into their realm, including the Caucasus, Transoxiana, Sindh, the Maghreb, and eventually, the Iberian Peninsula.

The Umayyads faced several challenges during this period of growth. The Second Fitna (680-692) threatened the stability of the caliphate, but the Umayyads emerged victorious, crushing rebellions with force. This period also saw the tragic events at Karbala in 680, where Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, was killed by Umayyad forces. This event would have long-lasting repercussions, deepening the schism between Sunni and Shia Muslims that lasts to today.

The Golden Age of Expansion

1. Armenia

In 645–646 CE, Mu’awiya’s general Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri launched an offensive against Byzantine-controlled Theodosiopolis (modern Erzurum), capturing it and defeating Byzantine forces bolstered by Khazar and Alan troops. Habib then advanced toward Lake Van, securing the submission of local Armenian princes and capturing Dvin, the capital of Persian Armenia.

Despite these victories, Arab control over Armenia remained tenuous due to resistance from local leaders like Theodore Rshtuni. Rshtuni initially aligned with the Byzantines but later submitted to Arab rule in 653 CE when faced with renewed invasions. This submission marked a turning point, as Rshtuni became an Arab-recognized prince of Armenia. However, internal conflicts among Armenian factions and shifting allegiances between Arabs and Byzantines complicated the consolidation of Umayyad authority.

By 661 CE, following the resolution of the First Muslim Civil War, Mu’awiya reaffirmed Arab dominance over Armenia. The region was formally integrated into the caliphate by 705 CE, becoming part of the province of Arminiya alongside Caucasian Albania and Iberia. Under Umayyad rule, Armenian Christians retained political autonomy but were subjected to dhimmi status, enjoying limited religious freedom while contributing troops to caliphal campaigns

2. North Africa

The Umayyad conquest of Ifriqiya culminated in 698 with the capture and destruction of Carthage, marking the decisive end of Byzantine power in North Africa. The campaign was led by Hasan ibn al-Nu’man, a general under Caliph Abd al-Malik, commanding an army of approximately 40,000 troops. The operation was part of a broader effort to consolidate Umayyad control over the Maghreb after earlier setbacks and resistance from Byzantine and Berber forces.

Carthage had remained a key Byzantine stronghold despite earlier Arab incursions. In 697, Byzantine forces briefly recaptured the city in a surprise naval assault under John the Patrician. However, Hasan ibn al-Nu’man launched a counteroffensive in 698, besieging the city by land and sea. The Byzantines, despite their fortifications and resupply efforts, were overwhelmed by the relentless Arab assaults. Eventually, they abandoned the city, retreating to nearby islands like Sicily and Crete.

Following its capture, Carthage was utterly destroyed to prevent any future Byzantine resurgence. Its walls were torn down, its harbors rendered unusable, and its population either killed or enslaved. This destruction erased one of the last remnants of Greco-Roman influence in the region, leaving the area desolate for centuries.

The fall of Carthage symbolized not only the end of Byzantine dominion but also the integration of Ifriqiya into the Umayyad Caliphate, with Kairouan as the center of Islamic governance and culture in North Africa.

3. Magreb

Musa ibn Nusayr, a prominent Umayyad general and governor of Ifriqiya, played a pivotal role in the conquest of the western Maghreb, including modern-day Morocco, during the early 8th century. By 708/709, Musa had successfully extended Umayyad control to Tangier in the north and the Sous region in the south, effectively consolidating Muslim rule over much of Morocco.

Musa’s strategy involved both military campaigns and diplomacy. He respected local Berber traditions and avoided imposing Islam by force, which encouraged many Berber tribes to convert voluntarily. These converts, known as mawali, often joined his army, strengthening his forces for further conquests. Despite this diplomatic approach, resistance from some Berber groups required military action. Musa’s campaigns subdued key Berber confederations like the Hawwara, Zenata, and Kutama.

Tangier was a significant milestone in Musa’s westward advance. Its conquest marked the defeat of remaining Byzantine influence in the region and established a foothold for further operations. From there, Musa’s forces moved south to the Sous valley, securing control over strategic territories and expanding Umayyad influence to the Atlantic coast.

The conquest of the Maghreb under Musa ibn Nusayr not only solidified Umayyad control over North Africa but also laid the groundwork for future expansions into Iberia. His Berber lieutenant, Tariq ibn Ziyad, would later lead the historic invasion of Hispania in 711, initiating the Islamic era in Al-Andalus.

4. Transoxia

The Umayyad conquest of Transoxiana by the Umayyad viceroy al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf leveraged military prowess, strategic alliances, and administrative pragmatism to subdue the fractious principalities beyond the Oxus River. By 713, his campaigns had secured nominal Umayyad control over key cities like Bukhara, Samarkand, and Ferghana, though long-term stabilization required decades of further conflict.

Qutayba’s first major victory came in 705 with the reconquest of Balkh, a strategic hub in Tokharistan, followed by alliances with local rulers such as Tish of al-Saghaniyan. His forces then targeted Bukhara, exploiting internal divisions among its nobility. After a brutal two-month siege of Baykand (706), Qutayba sacked the city, executing its men and enslaving survivors—a tactic that deterred further revolts. By 709, Bukhara’s ruler Tughshada accepted tributary status, allowing Arab garrisons and the construction of a mosque.

Qutayba’s 711–712 campaign against Samarkand exemplified his blend of surprise and diplomacy. Feigning a retreat to Merv, he abruptly besieged the city, crushing a relief force from Shash. Samarkand’s ruler Ghurak negotiated surrender, permitting an Arab garrison and mosque, but Qutayba later occupied the citadel, forcing Ghurak to flee north. Similarly, Khwarazm and Ferghana fell by 713 through a mix of force and co-opting local elites.

Despite Qutayba’s successes, Transoxiana remained volatile. The Sogdian elite resented Arab dominance, and the Türgesh launched counterattacks after 715. Most gains unraveled posthumously until Umayyad forces reasserted control in the 740s. Eventually, Qutayba’s campaigns established foundational Arab-Islamic governance, blending military garrisons, tax systems, and religious infrastructure. In 751 the Umayyad forces reached the huge Chinese Tang empire where it defeated them in the Battle of Talas.

5. Sindh

The Umayyad conquest of Sindh, completed in 712 CE, marked the first successful Arab incursion into the Indian subcontinent. Led by Muhammad ibn Qasim, a 17-year-old general under the Umayyad Caliphate, this campaign aimed to subdue the region ruled by Raja Dahir, a Hindu monarch of the Brahmin dynasty. The conquest was initiated by Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the governor of Iraq, who meticulously planned the expedition after earlier failed attempts to punish Raja Dahir for his inability to curb piracy in the Arabian Sea. These pirates had disrupted Muslim shipping and kidnapped Muslim women, providing a casus belli for invasion.

Muhammad ibn Qasim’s forces consisted of 6,000 Syrian cavalry, camel riders, and siege equipment, including catapults. The campaign began with the assault on Debal (near modern Karachi), where Qasim’s army breached the fortified city walls and destroyed its prominent temple. This victory sent shockwaves across Sindh and paved the way for further advances.

After securing Debal, Qasim marched northward, capturing towns like Nerun and Sehwan with minimal resistance. The decisive confrontation occurred near Aror (modern Rohri) on the banks of the Indus River. Raja Dahir led his troops atop an elephant but was killed in battle. His death demoralized his forces, leading to their defeat and the collapse of his kingdom.

Following Dahir’s fall, key cities such as Brahmanabad and Multan were captured by 713 CE. The region was incorporated into the Umayyad Caliphate as a province. Muhammad ibn Qasim’s administration promoted trade, established law and order, and allowed religious freedom for Hindus while spreading Islam. This conquest laid the foundation for subsequent Islamic influence in South Asia.

6.Hispania

The Umayyad conquest of Hispania (modern-day Spain and Portugal) began in 711 and would prove to be one of the most significant and lasting achievements of the dynasty. The invasion was led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, a Berber commander serving under the Umayyad governor of North Africa, Musa ibn Nusayr.

On July 19, 711, an army of Arabs and Berbers landed on the Iberian Peninsula, possibly at Gibraltar (which derives its name from Jabal Tariq, or “Mountain of Tariq”). The Visigothic Kingdom that ruled Hispania was weakened by internal divisions, and over the next seven years, through a combination of military campaigns and diplomatic agreements, the Umayyads brought most of the Iberian Peninsula under their control.

The conquered territories were organized into a new province called Al-Andalus, administered from Córdoba on behalf of the Umayyad caliphate in Damascus. The Umayyads advanced into southern France but were halted by the Franks of Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours in 732, marking the northernmost extent of Muslim expansion in Western Europe.

The conquest of Hispania was not a single, swift campaign but a process that continued for several decades. Some regions, particularly in the mountainous north, remained unconquered and would later form the basis for Christian kingdoms that would eventually initiate the Reconquista.

The Umayyad conquest brought significant changes to the Iberian Peninsula. The new rulers implemented a system of governance that allowed for a degree of religious and cultural autonomy. Christians and Jews, while subject to certain restrictions and taxes (jizya), were allowed to practice their religions as dhimmis (protected peoples).

The early period of Umayyad rule in Al-Andalus saw the gradual development of a unique Andalusian culture. This culture blended elements from the diverse populations of the peninsula, including the indigenous Hispano-Romans, Visigoths, Berbers, and Arabs. Over time, this would lead to significant advancements in science, philosophy, and the arts.

The Fall of the Umayyad Caliphate and the Emirate of Córdoba

In 750, the Umayyad caliphate in Damascus was overthrown by the Abbasid revolution. Most members of the Umayyad family were killed, but one prince, Abd al-Rahman I, managed to escape to North Africa.

In 756, Abd al-Rahman I crossed to Al-Andalus and established himself as the independent Emir of Córdoba, effectively creating a separate Umayyad state in the West. This marked the beginning of the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba, which would later evolve into the Caliphate of Córdoba in 929.

Under Abd al-Rahman I and his successors, Córdoba became a center of learning and culture. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, begun under Abd al-Rahman I in 785, stands as a testament to the architectural and artistic achievements of this period.